In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was a well-kept secret among scholars that magic in the ancient Mediterranean was prevalent. Historians wanted to keep the method low-key because their idealized image of the Greeks and Romans was not assisted by it. Magic, however, is a valid field of academic study today, offering insights into ancient systems of belief and cultural and social processes.

While in history, magic was discouraged and often even punished. Still, it thrived all the same. It was publicly condemned by authorities but continued to overlook its firm grip.

A common form of magic was erotic spells. Writing erotic spells, creating enchanted dolls (sometimes called poppets), and even guiding curses against rivals in love, competent magic practitioners charged fees.

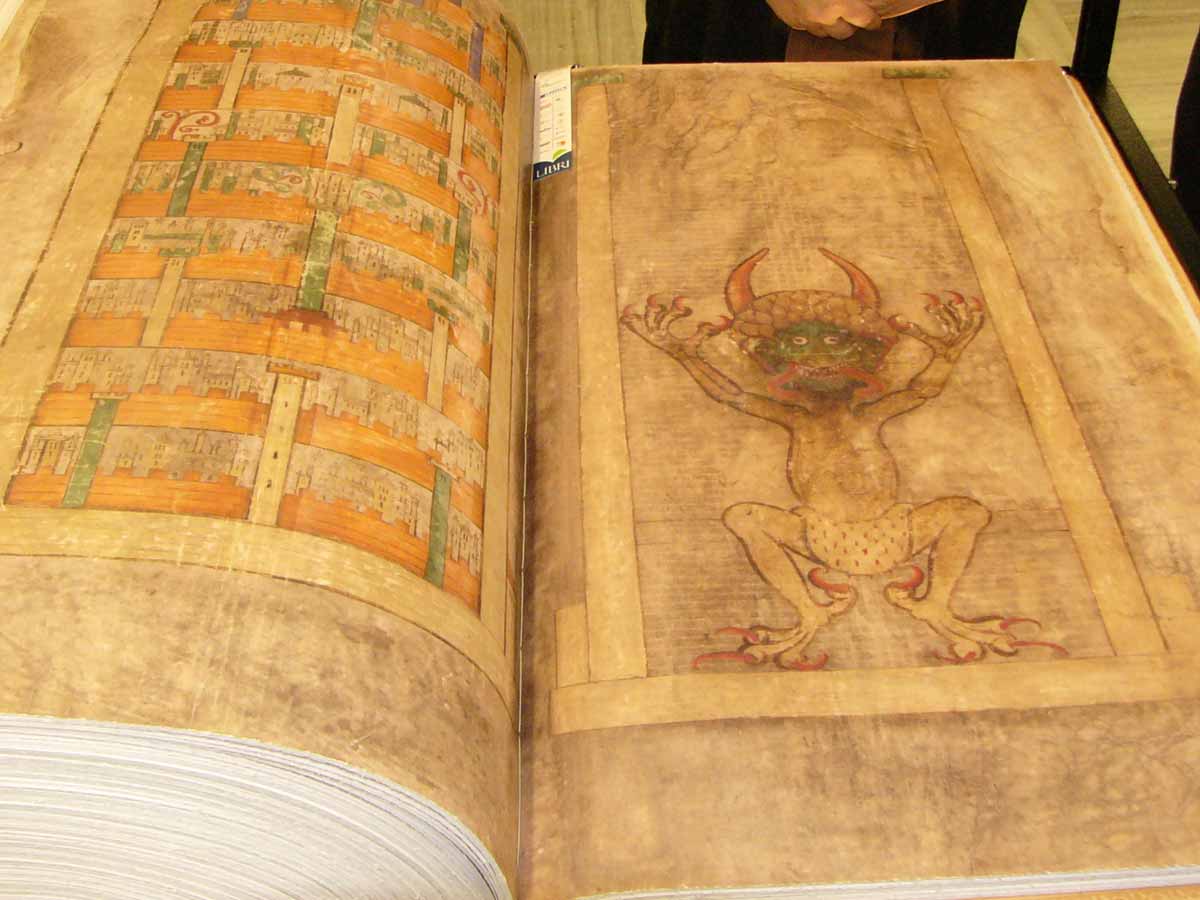

In archaeological evidence, spellbooks, and literature from both Greece and Rome and Egypt and the Middle East, magic is widely attested. For example, from Graeco-Roman Egypt, the Greek Magical Papyri is a broad set of papyri listing spells for many purposes. The collection was assembled from references from the second century BC to the fifth century AD and comprises multiple enchanting amulets.

Some spells include creating dolls to represent the objective of desire. The instructions specified how to make an erotic doll, what words should be said about it, and where to deposit it.

Such an entity is a type of sympathetic magic, a form of enchantment that works along with the “like results like” concept. The spell-caster assumes that any intervention is performed on it, whether physical or psychic, will be passed to the person it serves while enacting compassionate magic with a doll.

The “Louvre Doll” (4th century AD), the best-preserved and most infamous mystical doll of antiquity, portrays a nude female kneeling, fixed and pierced with 13 needles. Created from unbaked clay, the doll was found in Egypt in a terracotta vase. Inscribed on a lead tablet, the corresponding spell records the woman’s name as Ptolemais and the man. They created the spell or hired a magician to do so, as Sarapammon.

Violent, brutal language

The language and imagery use in the spells were harsh that followed such dolls, or rather, the spells of mythology on all kinds of subjects. Often violent, brutal, and out of any sense of caution or guilt, ancient spells. In a modern sense, the vocabulary is both terrifying and repellent in the spell that comes with the Louvre Doll. One part of the spell aimed at Ptolemais, for instance, reads:

“Do not encourage her to eat, to drink, to hold out, to go out, or to find sleep.”

Another portion reads:

“Drag her by the hair, the guts, before she doesn’t scorn me anymore.”

Such language is hardly representative of any feeling, or even attraction, of affection. The spell can strike a modern reader, particularly when coupled with the doll, as obsessive and even sexist. Indeed, the purpose behind the spell, rather than finding love, implies seeking power and conquest.

Also Read, MERFOLK- The tales of mermaids and mermen

But in a male culture where rivalry was intense in all facets of life, and the objective of victory was primary, the violent language was characteristic of spells ranging from success in a court case to the domination of a chariot race. Indeed, one hypothesis suggests that the more strong and effective the spell is, the more vicious the words.

Love potions

Most ancient evidence attests to men and their clients as both skilled magical practitioners. To perform most magic, there was a need to be literate (most women were not educated) and be open to clients. Some women, however, have also engaged in erotic magic. For instance, in ancient Athens, a woman was brought to court on charges of trying to poison her husband. In a speech made on behalf of the defense in the trial, which was reported around 419 BC. It involves protecting the woman, who claimed that she did not wish to poison her husband but administer a philtre of love to revitalize the marriage.

The speech, entitled Against the Stepmother for Antiphon’s Poisoning, clearly shows that the Athenians performed and believed in potions of love and may indicate that women’s protection was done with this more mild form of erotic magic.

Desire between women

Two spells deal directly with female same-sex preference within the multiplicity of spells discovered in the Greek Mystical Papyri. In one of these, a woman named Herais tries to implore a woman named Serapis magically. In this spell, the gods Anubis and Hermes are called upon in this spell, dated to the second century AD, to carry Serapis to Herais and bind Serapis to her.

In sorcery, gods and goddesses are summoned continuously. Anubis is included in the spell to attract Serapis, for instance, based on his role as the god of Egyptian sorcery’s secrets. Hermes, a Greek god, was also used because he was a useful choice as a messenger god in spells that sought contact with others.

The same societies’ mystical practices were underpinned by the traditional hierarchy of clearly bifurcated gender roles of active (male) and passive (female) partners based on patriarchy that championed supremacy and achievement at all costs. Yet, it is essential to remember that because of the conventions that underlined ancient spells, aggressive language is used even in magic involving people of the same sex.

When it comes to sexual practice and conventions, magic remains, in part, a mystery. For instance, the two same-sex spells from the Greek Magical Papyri testify to the reality of romantic desire among ancient women. Still, they do not shed light on whether in Roman Egypt this kind of sexuality was condoned.