It may be difficult to conceive that summer will offer lighter days amid a spring that is growing more uncomfortable.

So many inquiries, so few solutions. These anticipated books, however, which include a biography by Gene Andrew Jarrett, novels by Akwaeke Emezi, Ottessa Moshfegh, and Morgan Talty, as well as a study of menswear edited by Vicki Karaminas, Adam Geczy, and Pamela Church Gibson, can direct us as we look for new ways to dress, imagine a freer future, and reimagine our walk to the food court. Find some shade and read these books to lower your body temperature.

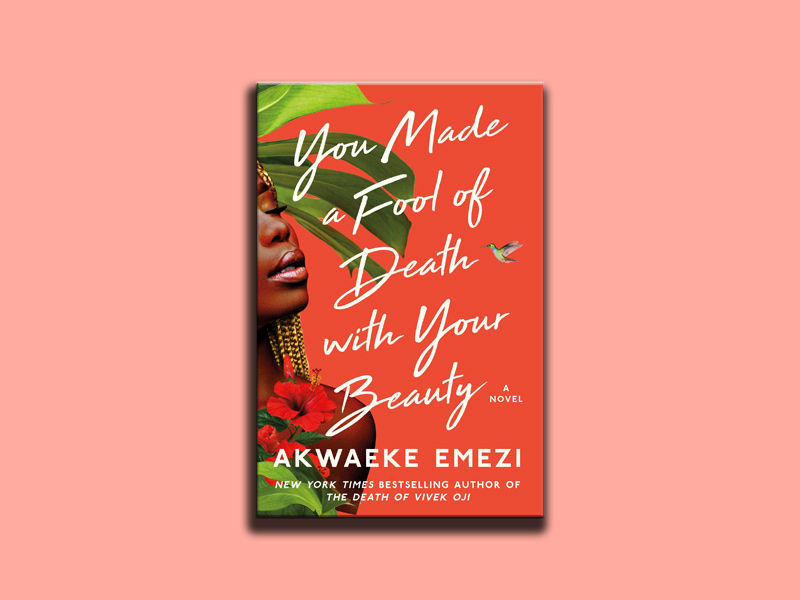

Akwaeke Emezi’s: You Made a Fool of Death With Your Beauty

Feyi Adekola, a young woman whose partner passed away five years earlier, struggles to date once more in Emezi’s most recent book. Feyi is both thrilled and skeptical when she finally finds a fresh, passionate love.

Will a relationship this ferocious consume her entire life? Fans of Emezi’s earlier works will enjoy the author’s brave first attempts at romance as well as the author’s beautiful prose and multi-layered characters. The work skillfully illustrates the fortitude of choosing love even in the face of complete despair. It is both a love story and a story of profound loss.

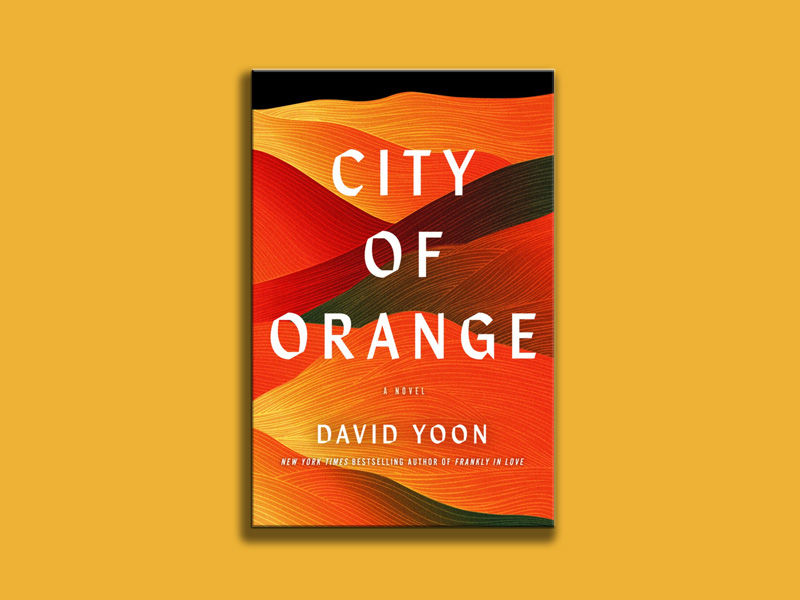

David Yoon’s: City of Orange

David Yoon’s very understated postapocalyptic novel explores how the great, final devastation of human life might be felt on a more personal level as climate change ravages people, the natural world, and our imaginations.

The intriguing opening of the City of Orange has a dissociative amnesiac protagonist who mysteriously awakens under a bridge and wonders where everyone is.

His experiences with people and animals show him that perhaps not everything is as it seems as he warily investigates his surroundings, forages for food, finds shelter, and tries to reconstruct who he is and what has happened. The end of life as we know it may just be the end of life as we thought we knew it, thanks to subtle and stark twists that bring an often languid tale more vividly into focus.

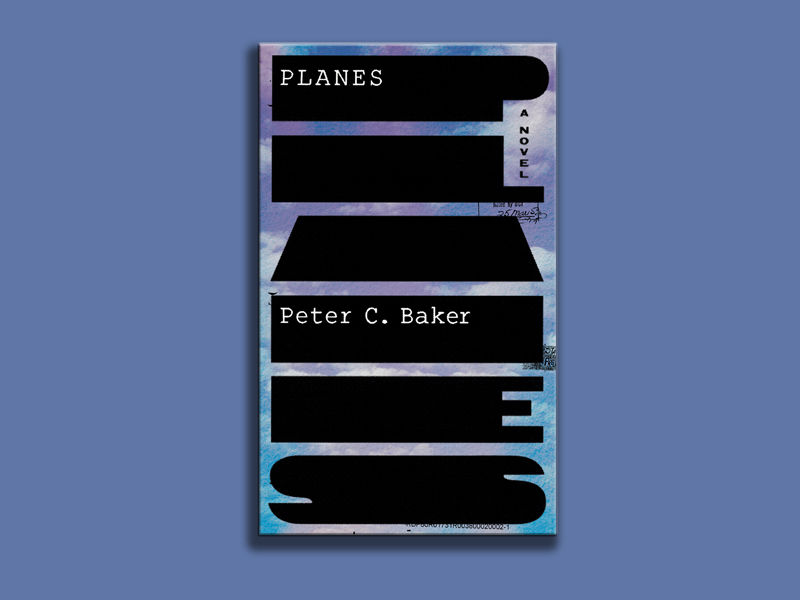

Peter C. Baker’s: Planes

As a journalist, Peter C. Baker has written on Chicago police brutality, pedestrian deaths nationwide, and the theft of the manuscript for his first book by a con artist. Baker’s curiosity about the structures that support our interpersonal connections is channeled in that book*, Planes.

Mel, whose marriage to a former activist like herself is challenged by an affair with a fellow school board member, and Amira, who is living on autopilot in Rome while her husband writes to her from prison in Morocco, are the main characters of the novel. Given Baker’s history, it becomes reasonable that these seemingly unrelated narratives converge on a level that is more political than psychological. His curiosity also seems to permeate his writing.

Nina LaCour’s: Yerba Buena

Two Los Angeles working-class ladies are slowly falling in love while flashes of their pasts keep appearing in the present. As an adolescent runaway, Sara Foster arrives in Los Angeles.

She later establishes herself as a mixologist at the upscale eatery Yerba Buena, where she is renowned for using the herb’s namesake as a special ingredient in her drinks. She meets Emile Dubois there, a recently hired floral designer with a similarly troubled past. In the first work of adult literary fiction by renowned YA novelist Nina LaCour, their courtship might never realize its complete potential.

Mecca Jamilah Sullivan’s Big Girl

This bildungsroman centers on protagonist Malaya Clondon’s African dance lessons, her weekly Weight Watchers meetings at an A.M.E. church, and her predominantly white private school. It is about a young Black girl whose wild appetites for food, affection, and freedom confound the small imaginations of those around her.

Malaya is continually subjected to criticism of her appearance and behavior from others, and this sense of being seen teaches her what her body means to others before she understands what it can mean to herself.

She continues to be a diligent observer of her complicated world, constantly recording the tastes, sounds, sights, and social interactions that characterize her part of Upper Manhattan at the turn of the 20th century. A rich and incisive study on indulgence, identity, and inheritance, Sullivan’s debut is a narrative for people whose need for bodily autonomy and self-determination cannot be satisfied by the rations of a greedy society.

Vicki Karaminas, Adam Geczy, and Pamela Church Gibson’s: Fashionable Masculinities

Critical studies of men’s relationships to the subject have historically been on the outskirts of academia, and even then, they were hardly even on the radar. But significant advancements in this area, along with a significant cultural shift over the previous 10 years, have allowed an essay collection like Trendy Masculinities to be… fashionable. Although this is an academic work, some of the top experts in the subject have contributed to it.

The book’s 16 chapters are accessible to anyone interested in gender and clothing, and Shaun Cole published one of the best examinations of how gay men utilized clothing to express their sexual orientation.

Christopher Breward wrote the classic history of the suit. The construction of Black masculinity through clothing, Harry Styles’ “anti-gender” expression, and how men employ exercise, tattoos, waxing, and tanning to create a new “spornosexual” body made popular by athletes and reality stars are all examined. In picking apart our conception of manhood, Fashionable Masculinities demonstrates how “masculinity has become a style that may be worn, assumed, or abjured.”

Elaine Castillo’s: How to Read Now

I must admit that I enjoy the warm, fuzzy feelings that reading induces. In Marilynne Robinson’s books, domestic places exude a calm satisfaction, yet in Susanna Clarke’s epics, created worlds inspire majestic awe.

It’s okay that we read to feel! But Castillo has higher goals for all of us, and in this collection of interconnected essays, she makes an effort to tear reading away from cotton candy aspirations of uniting people in sympathetic harmony and reposition it as a more difficult—but ultimately more fruitful—task. Although this argument is not new, it has been intensifying over the past ten years as criticism, particularly online, has crept towards lists like the one in question.

Emmanuel Carrère’s: Yoga

The autobiography Yoga by Emmanuel Carrère, which John Lambert just translated from French, follows the author to a yoga retreat where he hopes to improve his meditative abilities. When he learns of the Charlie Hebdo shootings, in which a close friend was killed, this quest for mindfulness is put on hold. As a result, he leaves the retreat early and enters a time of psychological turbulence during which his marriage, an affair, and his job all fall apart.

A legal dispute between Carrère and his ex-wife over the book resulted in an agreement by Carrère to send the ex-wife mentions of her in his work before publication and to make all requested changes.

In a twist akin to Show About the Show, allegedly inaccurate portrayals of the period of his life the book narrates as well as of his ex-wife and their daughter were the cause of the legal dispute. Stay for the breathing exercises and come for another chapter in the ongoing discussion of authorship and ownership.

Mariame Kaba and Andrea Ritchie’s: No More Police: A Case Against Abolition

In this article, Mariame Kaba and writer-organizer Andrea Ritchie argue against the use of police. The book investigates the numerous ways that police fail to keep people secure and implores us to find alternative methods of establishing community safety. It is a mix of historical lessons and summons to action.

Also read: Top 10 Books On Personal Finance to Master Money Management

The book provides readers with an uncommon view into the psyche of seasoned organizers who have long stayed dedicated and positive in this work because both women have been actively involved in abolitionism (Kaba’s work focuses on prisons, and Ritchie’s has focused on police brutality).

The book provides readers with an uncommon view into the psyche of seasoned organizers who have long stayed dedicated and positive in this work because both women have been actively involved in abolitionism (Kaba’s work focuses on prisons, and Ritchie’s has focused on police brutality).

No More Police, a handbook and a roadmap, challenges readers to envision not merely a future without police, but a society in which police are not required because we live in communities that are tranquil, resourceful, and ultimately safe.