“The Hollow Men” was written by T.S. Eliot in 1923, five years after World War I ended in 1918. Eliot was an American expatriate living in London, England at the time. His poetry of the 1920s reflected on the war’s aftermath, particularly its impact on European ethical and literary traditions.

The First World War drastically altered Europe. In horrific conditions made possible by new technology such as poison gas and machine guns, around 10 million people died and 30 million were injured.

Russia’s, Austria- Hungary’s, and the Ottoman Empire’s historic empires all fell apart. Uprisings led by socialists, communists, and anti-colonialists became common. The Treaty of Versailles humiliated Germany and forced it to accept financial responsibility for the war, fueling the bitterness and poverty that led to the Second World War.

Many of the British Empire’s traditions, including class and gender norms, were upended. Diseases spread quickly; the 1918 flu pandemic claimed the lives of at least 50 million people. The globe changed drastically in four years. Those who remained were taken aback.

Modernist writers such as Eliot strove to find new ways to depict the disillusionment and devastation caused by the Great War. The poem “The Hollow Men,” written in 1925, is about trauma and despair. It, like “The Wasteland,” written three years before, seeks to piece together a broken Europe and listens for echoes of meaning.

It seeks religious faith—and bears witness to its failure to find it. A few years later, Eliot would convert to Anglicanism and write his first significant Christian poetry, “Ash Wednesday,” in 1927. Eliot was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1948.

Analysis:

The poem begins with two epigraphs that allude to two examples of “Hollow Men,” one fictional and one historical. The primary protagonists have then introduced: a gang of scarecrows leaning together. In a chorus, these Hollow Men narrate the poetry. They bemoan their situation: their bodies are paralyzed, and their discourse is worthless.

Also read: Pablo Neruda Poetry: 20 love poems and a song of despair

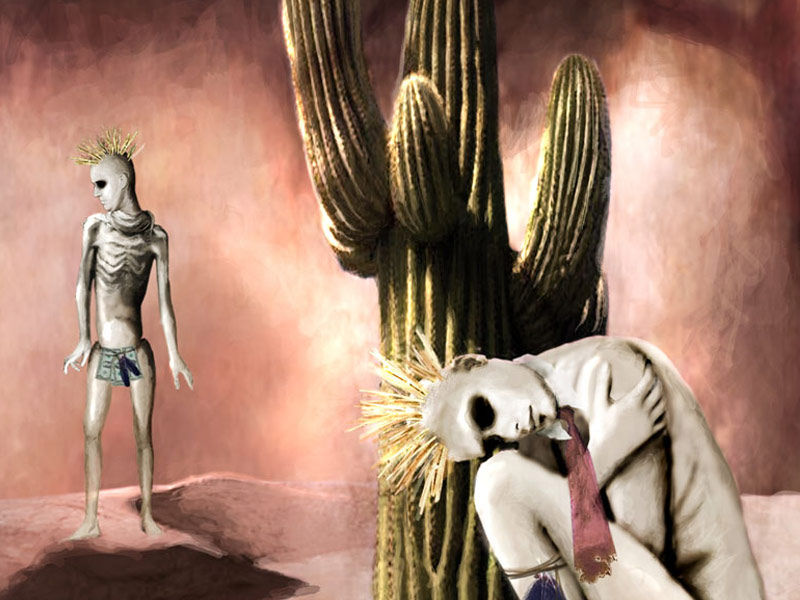

Dead ancestors on the opposite side of a mystical river see and judge the men. One of the Hollow Men expresses his concern at facing the scrutinizing eyes of the dead while sleeping. They make an attempt to pray but fail. The Hollow Men oscillate between religious faith and despair in a desert valley on the brink of an overflowing river under dying stars.

They dance around a cactus while repeating a twisted rendition of a nursery rhyme. The priest then talks and the congregation responds in an antiphonic parody of a Christian worship session.

As they attempt to recite the Lord’s Prayer, the shadow of death paralyzes all activity and the language of the chorus disintegrates. The poetry and the world come to an end with an anticlimactic whimper.

Themes of the poem:

Failure :

The topic of failure is central to “The Hollow Men.” Eliot collects failure examples in the figures of Kurtz and Fawkes, both of whom tried to live an anarchic existence. He also investigates it under the following subthemes: paralysis, or a lack of will; impotence, or a lack of procreation; malaise, or a lack of imagination; and amorality, or a lack of faith.

Failure is also demonstrated poetically in “The Hollow Men”: the grammar breaks apart and the voices in the poem are unable to complete a prayer. The ritual of delivering poetry fails, as does language itself. The poem concludes with the end of the world, another failure, and it concludes miserably, with the embarrassing sound of a whimper.

Faith:

Faith is examined through contrasts in “The Hollow Men.” The first distinction is between the Hollow Men, who are immobilized by amorality, and those who have crossed the river into the afterlife with “direct eyes,” indicating faith and moral clarity.

Then there’s a contrast between the arid desert, the “dead land” of faithlessness, and the dream state in sleep when the narrator has access to a distant, fading world of faith, represented by the wind singing, the tree swinging, and the fading star.

The poem becomes more intense with declarations of religious aspiration and a concomitant rebirth of sadness.

Prayers are directed to a fractured stone, and the Christian vision of the “perpetual star, Multifoliate rose” is transformed into “the hope only/Of empty men.” A whimper, the final word, depicts a sound, conveying the paradox of asking for salvation without having the faith to create a word.