The Anarchy book review

William Dalrymple’s 2019 history book The Anarchy: The East India Company Corporate violence and The pillage of an Empire. It tells the story of the East India Company’s rise in the second half of the 18th century, against the backdrop of a collapsing Mughal Empire and the rise of regional powers.

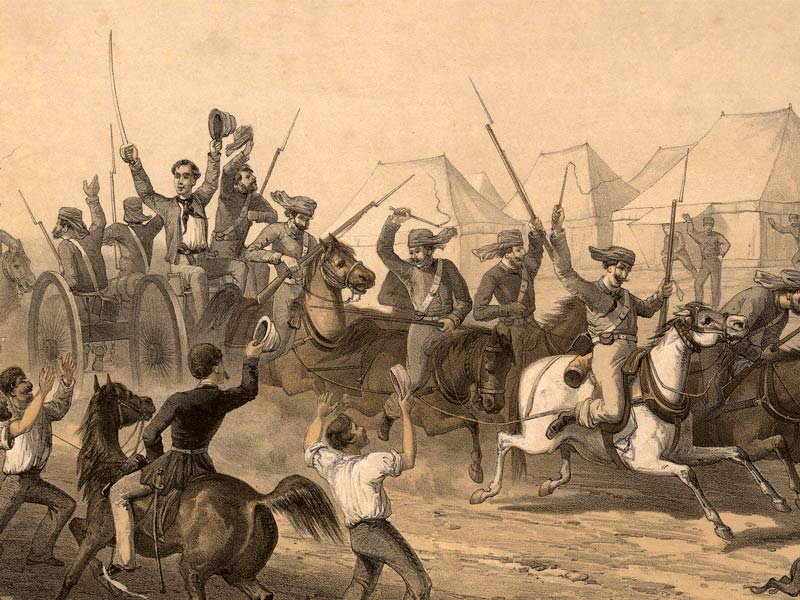

The book covers the history of the East India Company in the Indian subcontinent, beginning with the humble beginnings of the East India Company, which was founded in 1599 with a royal charter granting them a monopoly on all trade between England and Asia. By the end of the first half of the 18th century, they had established bases in Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras. The majority of the book is devoted to territorial conquests, beginning with the Battle of Plassey in 1757, which results in the conquest of Bengal, Mughal India’s richest province. By the end of 1803, they control the entire subcontinent and command a large private army.

The true story of the Battle of Plassey in 1757, which gave the company control of Bengal and which generations of British schoolchildren would remember as a glorious imperial victory, was far more complicated. The volatile, widely despised Nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud-Daula, had made an implacable foe of Bengal’s Marwari bankers, the Jagat Seths, who saw better opportunities in investing with the East India Company rather than supporting him.

The Jagat Seths offered the company more than £4 million (about a hundred times that in current terms, according to Dalrymple) to depose Siraj ud-Daula and replace him with a willing collaborator. Clive, who stood to make a fortune personally, gladly accepted. Plassey was, in fact, a “palace coup” carried out by a greedy opportunist.

It took six months for news to travel from Calcutta to London back then, and even when it did, few understood what was going on in Bengal. “Was it true,” a company director inquired, that “Sir Roger Daulat” was a baronet? What the directors did understand was that taking on territory meant taking on risk and expense. During the time , there was disdain for the grand lifestyle of the “nabobs” (chief among them, Clive) and concern about their corrupting influence on British politics led to the passage of a Regulating Act, which tightened parliamentary control over the company.

Warren Hastings’ “rule was as extractive as ever,” and his ruthless treatment of the company’s Indian subordinates led to his spectacular impeachment in 1787. Governors-general would be no less violent – only far more racist – in the aftermath of Hastings. Hastings was chosen to lead a cleaner administration because he was scholarly and hardworking, lived a simple life, spoke several South Asian languages, had a great affection for India and Indians, and sponsored scholarships on Indian culture.

Regardless of how well-known these events are to some – thanks, in part, to Dalrymple’s own work – Dalrymple’s spirited, detailed account will be reason enough for many readers to devour The Anarchy. But his more novel, and arguably more significant, achievement is in situating the company’s rise in the turbulent political landscape of late Mughal India. Because of the waves of invasion and civil war that shook Mughal power and allowed a slew of regional actors – of which the company was merely one – to gain ascendancy, contemporary Indian chroniclers dubbed this period “the anarchy.”

Dalrymple shares his observations from years of living in Delhi and immersing himself in Indian art, archives, and historical sites. He animates characters such as the brilliant Mughal general Najaf Khan, the vengeful Rohilla prince Ghulam Qadir, and the astute Maratha statesman Mahadji Scindia using reams of rarely used documents in Persian, Urdu, and other languages unearthed by skilled researchers and translators.

Dalrymple draws on previously untranslated or unknown sources, such as the Shah Alam Nama, a biography of Shah Alam II, the Mughal emperor during the majority of the events. He has a special talent for using Indian paintings as historical sources, which is complemented by the lavish illustrations in the book. And no one sets a scene like he does, whether it’s spying on an enemy fleet through an informant’s spyglass, or watching the waterlogged bodies of famine victims float down the Hooghly river, or wandering the trashed and ruined streets of ransacked Delhi.

To emphasise the importance of Indian actors in this history, he concludes The Anarchy with a highly symbolic event rather than a bureaucratic one, such as the company’s loss of its monopoly in India in 1813. “We are now complete masters of India,” a general declared. The emperor Shah Alam, the tragic hero in a book rife with villains – a figure who had witnessed the Persians sack Delhi, fought against Clive, survived an assassination plot, the rape of his family, and a hideous blinding – would spend his final years as a pensioner in the Red Fort, where he dictated “the first full-length novel in Delhi Urdu” about “a prince and princess tossed back and forth.

Dalrymple directs his conclusion toward a resounding condemnation of corporate brutishness and the governments that allow it. He writes that this story needs to be told because imperialism persists, but “it is not obvious how a nation state can adequately protect itself and its citizens from “Too much corporate spending.”