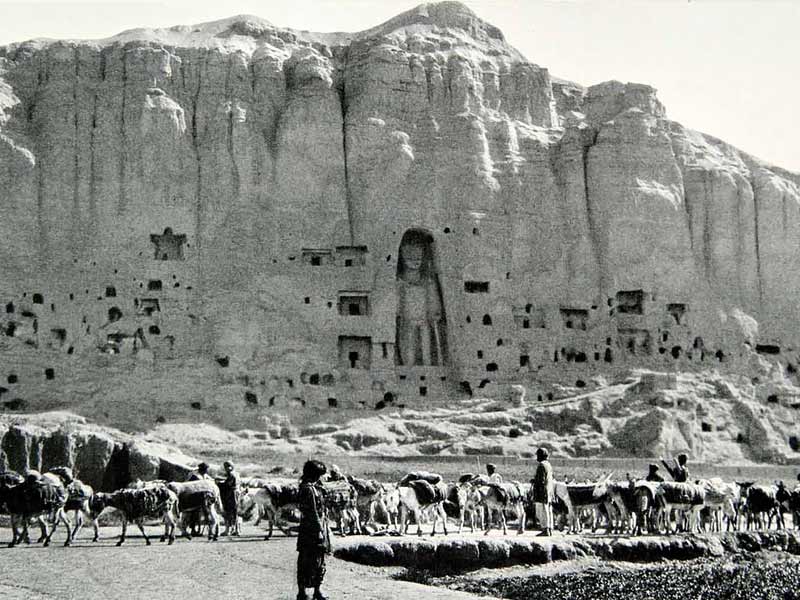

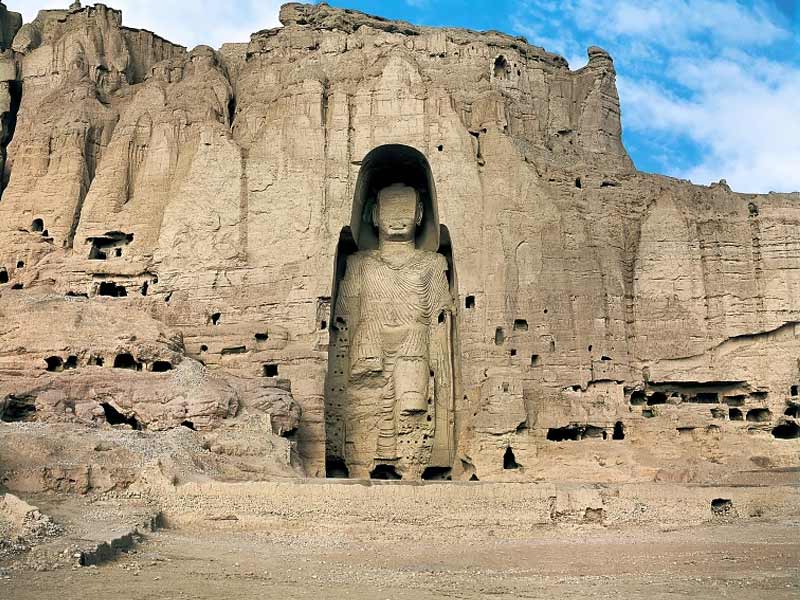

The Buddhas of Bamiyan are two enormous sculptures that were carved into the sandstone cliffs of the Bamiyan valley in central Afghanistan in the sixth century. They are each 115 and 174 feet tall. These sculptures are the greatest representations of the Gandharan Buddhist art school and the larger cultural context of Buddhism and its effects from the first to the thirteenth century.

The monuments were demolished by the Taliban for 25 days in 2001. Although Islam overtook Buddhism as the predominant faith in the area, many Afghans felt a huge loss when these Buddhist monuments were destroyed since they were a significant part of Afghan history and a source of national pride.

On the other hand, the site has already sustained irreparable harm. The empty area that the Buddhas formerly filled is still present, with vast fittings cut into the hillside, even if none of the Buddhas’ bodies are still there.

There is still a great deal of value in the site as it is now, even without the Buddhas, although their loss is a great tragedy and an unquestionable loss to world heritage. The absence of the Buddhas has an eerie quality to it; somehow, the voids left behind after their destruction have a presence of their own, which is seen as eerie. Perhaps a testament to the cultural and historical significance of the act of destruction itself is the ability of spectators to experience a sense of sadness or haunting while looking upon the remains.

A cultural heritage site’s worth is defined by its ability to accumulate traces of memory and history, according to the UNESCO definition.

The site presently, which contains both the memory of the ancient Buddhas and of current cultural struggle, should be kept as it is rather than rebuilt, even though the event that has been recorded tangibly on the bodies of the Bamiyan Buddhas was horrifically violent and terrible.

Any attempt at reconstruction, whether holographic, material, or otherwise, would fail to recognize how land, objects, and architecture are already changing and accumulating additional history. The restoration of the Buddhas would erase the massive acts of violence that have been committed at the site. The fact that the Buddhas are no longer there does not lessen the significance of the location; rather, the historical occurrence of their destruction has now been incorporated into its significance.

The historical Buddhas should still be engaged with, as they offer visitors the chance to visually interact with the original Buddhas, even though the cavities where the Bamiyan Buddhas once stood should be preserved as they are today rather than restored to a state before the Taliban attack in 2001. There has been a significant decline in tourism as a stable source of revenue since fewer tourists from abroad are traveling to the Bamiyan Valley expressly to visit these monuments. After the Buddhas were destroyed, a deliberate, nuanced effort to reshape the valley’s cultural and touristic environment was required to revitalize the location as a hub for cultural creation for both visitors from across the world and locals.

The Hazarajat region of central Afghanistan, where the majority of the Hazara people live, is divided into many provinces, the largest of which is the Bamiyan Valley. Since the late 19th century, the Hazaras, an ethnic minority in Afghanistan, have been oppressed.

Under Taliban rule, this opposition intensified, and the Hazaras suffered mass murders mostly because they adhered to the Shi’ite branch of Islam, which was opposed to the Sunni government. Just a few kilometers away from the Bamiyan Buddhas’ location, there is evidence of mass graves, and the Taliban is said to have killed some 15,000 Hazara people in all.

Indigenous peoples should be included as much as possible in conservation efforts for the Buddha caves, the new Bamiyan Cultural Centre, and the Bamiyan Valley as a whole. Employing local talent is a good idea for museum staff, site stewards, and upper-level administration of the entire site.

The project should similarly be designed and implemented by local consulting businesses that have a focus on ecological and ethical design. The rotational schedules of workers and even the design of the paths that lead through the complex and bring visitors between buildings and to the cavities of the Buddhas should be constructed with particular attention to the cultural and social specificities of the area. The smallest details of the logistics of conservation should take into account the particular dynamics of the region.

Other less obvious strategies can be used to revitalize the site for local valley people as well as for tourists from across the world, in addition to physically renovating the area around the Bamiyan Buddhas.

A commemorative festival or other event, for instance, may be entertaining for both locals and visitors and might last for a day, a weekend, or perhaps a whole week. The introduction of a recognized event might increase visitor interest and jump-start the economy.

Also read: 8 Excuisite Old Temples of Tamil Nadu

The goal of this effort would be to involve the whole Bamiyan Valley population. It would also energize the site as a dynamic hub for cultural interchange rather than preserving it as a historical or archaeological entity, where the community would only participate in certain activities.

Bamiyan and other important historical monuments in Afghanistan seem to be secure for the time being from violent attacks and planned destruction. The Taliban-led administration maintains that it wishes to protect Afghanistan’s “national treasures” and hasn’t yet interfered with any of the cultural initiatives.

The country needs technical and financial help to conserve its numerous valuable cultural assets, and the Taliban’s entrance has given security to formerly dangerous locations. According to local experts, there is a rare chance to visit locations that were previously inaccessible while working in the cultural sector to provide much-needed humanitarian relief.