The use of painting as a means of expression has endured throughout history despite the advancement of photography, cinema, and digital technologies.

Only a small percentage of the innumerable paintings that have survived over many centuries and millennia can be regarded as “timeless classics” that are well-known to the general public—and which, coincidentally, were produced by some of the most famous artists of all time.

Leonardo Da Vinci, Mona Lisa, 1503–19

Since its creation, the intriguing portrait by Leonardo da Vinci, which was painted between 1503 and 1517, has been the focus of two questions: Who is the subject, and why is she grinning?

Many other suggestions for the former have been made over time, including: That she is Caterina, Leonardo’s mother, as he remembers her from his infancy; that she is the spouse of Florentine trader Francesco di Bartolomeo del Giocondo (thus the alternate title for the work, La Gioconda); and finally, that it is a self-portrait disguised as another person.

Regarding that renowned smile, mankind has long been perplexed by its cryptic nature. Whatever the reason, Leonardo’s use of atmospheric perspective preserves Mona Lisa’s face of unreal tranquility while allowing the idealized scene behind her to fade into the distance.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring, 1665

The young woman in Johannes Vermeer’s 1665 study is astonishingly genuine and strikingly contemporary, almost like a snapshot.

This begs the question of whether Vermeer created the image using a camera obscura, a form of pre-photographic technology.

Aside from that, no one is certain who the sitter was, however, it has been suggested that she might have been Vermeer’s maid. She appears to be trying to establish an intimate connection across the ages as he paints her glancing over her shoulder and locking her eyes with the viewer.

Girl technically isn’t a portrait at all, but rather a representation of the Dutch tronie headshot style, which is more of a still life of the face’s contours than an attempt to capture resemblance.

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889

The Starry Night, Vincent Van Gogh’s most well-known picture, was produced by Van Gogh while he was a patient at the Saint-Rémy institution, where he had checked himself in 1889.

As the night sky comes to life with swirls & spheres of hurriedly placed brush strokes that are driven by the yin and yang of his personal demons and astonishment of nature, The Starry Night does seem to mirror his unstable mental state at the time.

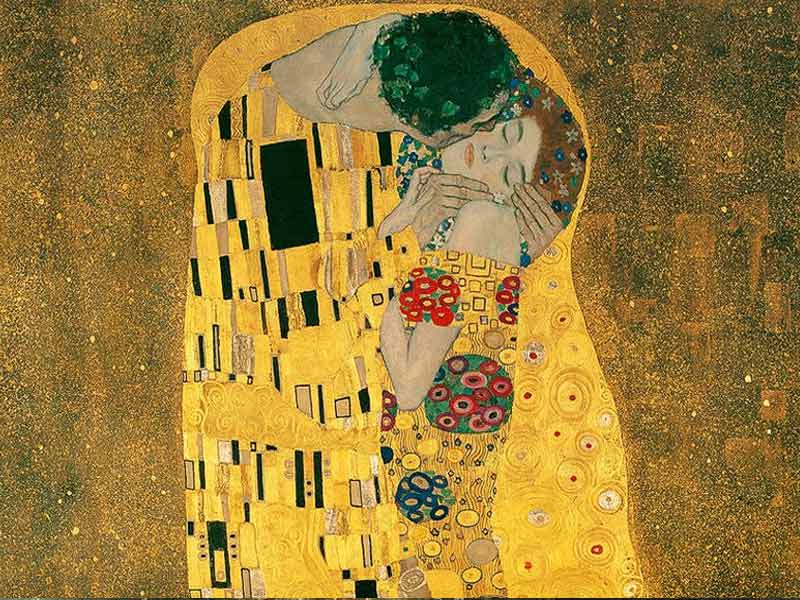

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, 1907–1908

The Kiss, a highly gilded and lavishly patterned representation of intimacy by Gustav Klimt from the turn of the century, mixes Vienna Jugendstil, an Austrian version of Art Nouveau, with Symbolism. Klimt depicts his characters as mythological entities who have been given contemporary makeovers on opulent surfaces.

The work represents the pinnacle of the artist’s Golden Phase, which lasted from 1899 to 1910 and was distinguished by the liberal application of gold leaf. The Basilica di San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, where he saw the famed Byzantine mosaics, inspired him to develop this method.

Also, Read Alia Bhatt Glowing Like A Princess This Summer

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, 1484–1486

Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, painted for Lorenzo de Medici, was the first full-length, non-religious nude painting since antiquity. The Goddess of Love is claimed to be inspired by Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci, who favors Lorenzo & his younger brother Giuliano and is said to have enjoyed.

Zephyrus and Aura, the wind gods, are seen blowing Venus on a large clamshell to land where the personification of spring is waiting in a cloak. Venus naturally infuriated Savonarola, the Dominican monk in charge of a fundamentalist crackdown on the secular inclinations of the Florentines.

The infamous “Bonfire of the Vanities” in 1497, which saw “profane” objects like books, paintings, and cosmetics destroyed on a pyre, occurred during his campaign. The Birth of Venus was supposed to be burned, but luckily, it was spared. Botticelli, however, was so alarmed by the event that he temporarily stopped painting.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, 1871

Whistler’s Mother, formerly known as Arrangement in Grey & Black No. 1, is an example of how the artist expressed his or her intention to produce work purely out of passion. The piece was created by James Abbott McNeill Whistler in his London studio in 1871, and it has the formality of an essay.

Whistler’s mother, Anna Whistler, is pictured as one of a number of elements placed in a succession of right angles. Despite Whistler’s formalist goals, the picture came to represent motherhood because of her stern countenance, which blends in with the composition’s rigidity.

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434

One of the most significant pieces produced during the Northern Renaissance, this composition is regarded as one of the earliest oil paintings ever produced. It is said to be a full-length double portrait of an Italian merchant and a woman who may or may not be his bride.

The work of art is actually a marriage contract, noted art critic Erwin Panofsky claimed in 1934. The painting is perhaps one of the earliest interiors to employ orthogonal perspective to render a sense of space that is close to the viewer’s own; it gives an appearance of a picture, you could enter.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1503–1515

In general, this strange triptych is seen as a distant forerunner to surrealism. In actuality, it’s the expression of a late medieval artist who thought that Heaven, Hell, and the Devil were actual places.

It’s not quite obvious whether the middle panel represents Heaven, but the left panel of the three images depicts Christ giving Eve to Adam, while the right panel shows the wrath of Hell.

In Bosch’s graphic image of Hell, the damned are assailed by enormous ears carrying phallic blades, while a bird-beaked bug king sitting on the throne devours the unfortunate before promptly defecating them out again. This chaotic collection of symbols has typically defied interpretation, which is why it is so well-liked.