The tale of Dujana resembles reading from unintelligible ruins from the past. The state’s long-forgotten history from the pages of the recent past was never attempted to be restored. Everything occurred during our lifetime.

The loss of its grandeur is one of the painful sights and memories that serve as a reminder of the egregious neglect displayed by everyone, from the State Government to the new residents who took over the arable land that the Musalmans who migrated to Pakistan after the partition of Punjab left behind.

It is a village that once had the status of the capital of a former princely state that was under the protection of British India and was ruled by Yusufzai Pathans, but it has since devolved into a horrific tale of ruin, collapsing buildings, neglect, and material theft

. There isn’t much left of the heritage that belonged to us in this formerly prosperous village, save for a few fine masonry buildings scattered here and there and graves of the dead covered in cow dung and household trash. It can be reached from a narrow, pothole-filled road off of the NH-352, which is located 11 miles from Jhajjar, the district headquarters, and 28 kilometers south of Rohtak town. As one draws near, one notices the Red Mosque’s pinnacles on its minarets.

There are farms on both sides of this mofussil road. One of them is a high school building, and the other is a Primary Health Center. These two historic structures in open brick masonry are on the village’s eastern edge. The masons working for the last Nawab of this tiny princely state, Iqtidar Ali Khan, created and constructed both buildings in AD 1929.

Abdus Samad Khan received favor from the wandering mendicant Durjan Shah to establish his headquarters or capital in the newly established principality. The Chief gave the location his name in honor of his owner. Khan’s ancestors originated in a remote area of Hindustan’s northwest frontier known as the Yusufzai territory. Iqtidar was the eighth person in a row to see the division of Punjab and decide to move to Lahore.

The late Seth Duli Chand of Dujana, whose ancestors served as the Nawab’s bankers, once revealed to this author that while he was safely transported to his new residence, he got rid of the majority of his immovable possessions before leaving. The Nawab had given the father of Seth Duli Chand his large-scale pencil portrait and a Hukkah cast in Belgian mold glass as tokens of appreciation.

After moving into the new location, Abdul Samad Khan constructed a Kachehri, residential haveli, and Zenana quarters. Subsequently, numerous other structures appeared, and a few wealthy merchants who accepted invitations to settle also constructed a few Havelis and shops. The royal structures were strong-looking, fortified, and long-lasting. The structures at Dujana were more beautiful than those constructed at Roshanara Bagh by the Nawab of Jhajjar.

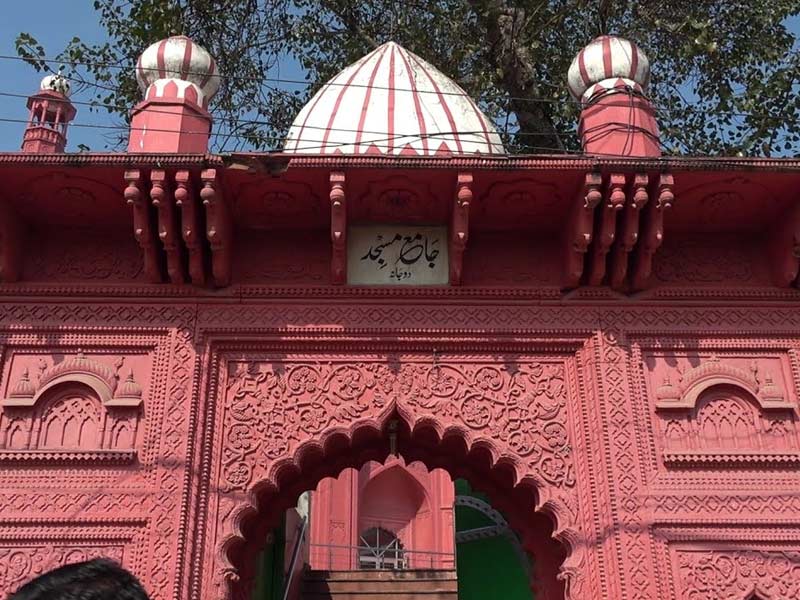

Mumtaz Ali Khan (b. 1864–1908d), the fifth Chief in line, had commissioned the construction of a fine mosque in front of the Kachehri in the closing decades of the 19th century. Its fascia and minarets featured shallow carvings of floral and geometrical motifs. It was covered in red sandstone that overlaid brick masonry.

The building’s vaulted entrance, which was reached by a flight of steps from the street, is still beautiful to look at. Dujana once had 30 mosques, ranging in size from small to large.

constructed over several years using lakhauri bricks and lime mortar. The largest vault roof design in this area was found on the Dhauli Masjid, which Hazi Ji built on the village’s western edge. It was harmed by the devastating floods of 1995. It soon gave way as the basement flooded.

The Khurshid Palace and an adjacent guest house, known as Bhagh wali Kothi, were the other notable piece of built heritage. This brand-new, roomy bungalow with some colonial architectural elements was constructed in 1919 by Khurshid Ali Khan, the eighth Nawab of Dujana, and is located behind the Red Mosque, which his father built.

In contrast to the Bagh wali Kothi, it is currently in ruins. The princely state managed 23 villages throughout its 144-year rule. Its territory, which was roughly 259 square kilometers and included the villages of Dujana and Mehrana as well as 21 other villages, including two large ones in the south called Bahu Jholri and Nahar, provided the chief with an annual income of about Rs. 77,000.

The Nawab was given four 16-pounder cannons by the British as part of a Treaty and was allowed to keep his 25 cavalries and 140 infantry for the benefit of the British as needed.

Two of the cannons now adorn the gates of the official residence of the Governor of Haryana, and the remaining one is located in Mansarovar Park in Rohtak. The cannons were cast in a foundry in Bengal and were lying neglected when the pieces were removed by L. Isa Das, a former collector at Rohtak, and restored and installed.

A soldier of fortune, Abdus Samad Khan had previously served Peshwa Baji Rao but later switched allegiances and fought alongside General Lake in the campaign against Scindia of Gwalior. He was given the territory in Haryana to establish a vassal state under the British due to his unwavering commitment to General Lake and his loyal services. On May 4, 1806, the Sanad, or certificate of the award, was given.

In the years after Punjab was divided and Haryana’s government annexed the region in 1948, the State’s assets withered. It was given to the Department of Education, which gave it little attention. Because neither the parent department nor the Department of Archaeology ever showed any interest in maintaining the history of the princely State of Dujana, wear and tear as well as vegetation took their toll.

Because neither the parent department nor the Department of Archaeology ever showed any interest in maintaining the history of the princely State of Dujana, wear and tear as well as vegetation took their toll.