Since May 3, there have been numerous interethnic conflicts in the northeastern Indian state of Manipur, mostly between the Meitei and Kuki. Over 75 people have died as a result of the violence, and over 1,700 buildings, including houses of worship and other facilities, have been set on fire. Additionally, there are currently 315 aid camps housing more than 35,000 individuals, many of whom have been relocated. These figures might be increasing as the combat goes on.

The techniques India has previously used during disturbances in the Northeast or Jammu and Kashmir have been substantially imitated in the state government’s response. This has included imposing military curfews, shutting down the internet, and sending over 17,000 soldiers and paramilitary groups with the authority to shoot anyone on sight in “extreme cases.”

Even while the violence in Manipur is among the worst the state has seen in recent memory, it is not unheard of in India’s northeast, where the identities of various ethnic communities have frequently been weaponized to further the goals of a select few powerful people.

Even decades after India’s independence, very little has been done to promote understanding between different communities regarding one another’s history, culture, and traditions. Any efforts toward peacebuilding in the medium- to long-term will have to take this weaponization of colonial fault lines into account.

Democracy at Gunpoint

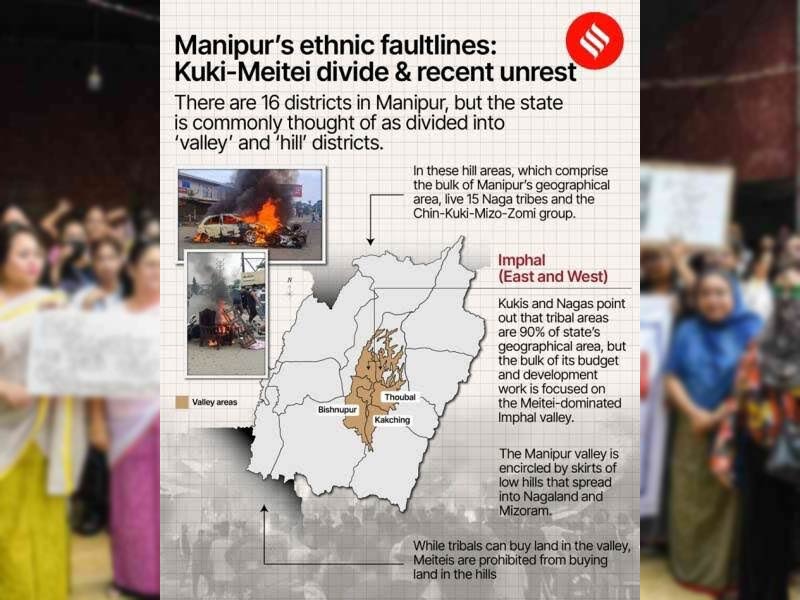

A valley is located in the “Land of Jewels,” Manipur, which is bordered by mountain ranges. 39 ethnic communities of various faiths, including Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam, as well as indigenous religious practices like Sanamahi, are found throughout the state. As the core of the conflict between New Delhi and numerous restive regions of the Northeast, opposition to the way Manipur was merged with India in 1949 laid the foundation for the early stages of resistance and separatist movements.

The Indian government implemented the contentious Armed Forces Special Powers Act in 1958 to crush this opposition. The statute grants the military and paramilitary organizations broad-based authority to “[maintain] public order” in “disturbed areas,” which has mostly been applied to the Northeast and Jammu & Kashmir.

The central government claims the act was required to maintain order in regions where the insurgency has a history, some dating back to India’s independence, despite criticism from rights groups and a severe lack of confidence between the state and federal governments in Manipur. The central administration has also stressed the danger of outside support for separatist movements in the Northeast (and elsewhere).

Several competing claims to ethnic and communal homelands exist in the region today, and those claims are being defended by armed insurgency organizations. There are roughly 30 Kuki-armed rebel organizations, many Naga groups, and at least four valley-based armed groups in Manipur. The state saw a “war within a war” due to the development of armed organizations, which were once thought to number in the 60s.

The state became the hub of widespread gun smuggling, narco-, and people trafficking as those with tight ties to governmental power profited from the unrest. In state elections, armed organizations frequently support candidates. Insurgent groups reportedly wrote a letter to Indian Home Minister Amit Shah in 2019 asking for a party ticket to be given to a candidate of their choosing, although the armed group later denied this. In 2022, two Kuki insurgent groups released statements supporting the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP).

Civil society organizations in Manipur noted that the 2022 elections were overshadowed by “open intimidation” from militant groups and violence across polling locations. Northeast politicians have reported intimidation by opposing armed groups. The result has been “democracy at gunpoint” in this vulnerable area.

Cause of the Most Recent Conflict

The most recent violence started after the Manipur High Court requested that the state government consider giving the Meitei community, which makes up the bulk of the population in Manipur, Scheduled Tribe status. The Meitei would have enhanced access to advantages, including reserved seats in government, under this status, which would guarantee protection under the Indian Constitution.

This status had long been demanded by the Meitei population in Manipur. There were serious worries, meanwhile, that this might widen racial gaps, especially among the Kuki and Naga Indigenous people. The All-Tribal Students Union of Manipur conducted a protest demonstration on May 3 shortly after the court’s announcement.

The Anglo-Kuki War Memorial Gate had reportedly been burned down when rumors of the violence first spread that day. This provoked the Meitei to retaliate by setting fire to several Kuki localities in the Imphal Valley, inflicting multiple injuries. In response, the Kukis burned several villages in Churachanpur that were home to the Meitei people.

While it is possible to pinpoint the protests as the immediate cause of violence in Manipur, tensions within the state’s indigenous communities had been building for some time. For example, the Kuki people, who predominantly reside in the hill regions surrounding the capital valley, have been viewed as being the target of the present state government’s treatment of Indigenous land rights concerns.

There have been evictions in Kuki communities as a result of efforts to survey reserved forests in the hill regions, which were ostensibly made to stop the cultivation of poppies.

Another area of concern is the current land imbalance between Indigenous populations: Kukis and other tribal people can purchase land in the valley, but Meiteis cannot do so in the aforementioned hill regions.

The Meitei Indigenous community has also experienced a rise in insecurity as a result of the flood of refugees following the military coup in neighboring Myanmar in 2021, particularly those from the Sagaing region who have strong ties to the Kukis.

The people most impacted in both communities are women and children, even though those in charge of the firearms, drugs, and politicians make the real decisions in the fight. To further a few people’s agenda, the identities of various ethnic communities have been weaponized in the ongoing struggle.

Also, Read New Parliament House: Inauguration, architecture, and purpose

The Conflict’s Development

While it has been difficult to obtain credible information from Manipur, photographs and accounts from the state depict an ongoing “war zone,” with heavily armed insurgents roaming, villages arming themselves, and a severe decline in confidence between citizens, administration, and security.

Social media posts that make it through the internet blackout are frequently filled with messages of hatred, discord, and misery. Essential goods are becoming increasingly expensive, and trucks transporting food, medicine, and other necessities have become trapped. While it is unknown how the issue will play out in the medium term, two tendencies should be kept an eye on:

The Indian state’s response. The central authority was deafeningly silent at the commencement of the unrest. Opposition parties have accused the BJP of focusing too much on the forthcoming elections and of using silence to incite violence.

Even though the violence has been ongoing for nearly a month, India’s Home Minister Amit Shah just arrived in Manipur for a four-day visit intended at “restoring normalcy” to the state, and India’s chief of army staff has also recently visited Manipur to assess the situation.

On June 1, Shah announced the formation of a judicial probe led by a former High Court judge to “investigate the violence” on behalf of the federal government. He also announced the formation of a peace committee comprised of representatives from various groups, the construction of additional fencing along the Myanmar border, and the return of an estimated 1,420 guns taken from local police since the start of the violence.

However, continuous violence will be a major determining factor in whether these obligations can be realized. Armed organizations continue to exploit the situation on the ground, while others have expressed alarm about cross-border attacks. Given the worries and commitments to increase border fencing, India will almost certainly need to interact with its regional neighbors if the violence persists.

Prospects for Reconciliation. Several towns around the state and region are hosting peace and prayer gatherings, religious leaders have called for peace, and others have advocated for the formation of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Women’s organizations in northeast India have issued petitions and established “Mothers Peace Committees” in several towns.

Ending the current violence and encouraging long-term reconciliation initiatives, on the other hand, are fundamentally two distinct – albeit interconnected – goals. Any reconciliation must grapple with the legacy of bloodshed from multiple insurgencies, as well as the government’s often heavy-handed actions, which have contributed to long-term trauma within the state.

persons in Manipur have suffered greatly for years as their rice fields have been converted into battlefields and tranquility has been snatched away by a few power-hungry persons who have manufactured discord and fostered bloodshed. Citizen-centric conversations and civil society engagement will be critical in overcoming decades of profound suspicion and historical suffering that have polarized Indigenous communities across the area.

Indigenous peacemaking projects, truth-telling, and forgiveness ceremonies may be a good place to start to heal the damaged hearts and minds of communities that have been ravaged by violence for decades. Women in peacebuilding are also required to kick off what will be a protracted process of establishing responsive government and transparency in the region.