Despite $3.59 trillion in record-breaking exports and a 7% increase in exports, China’s government failed to meet its 5.5 percent GDP growth goal for 2022. The economy barely increased by 3%, according to official statistics—one of the poorest showings in close to 50 years—largely because of the uncertainty brought on by frequent COVID-19 lockdowns.

Chinese authorities recently underlined their commitment to recovering the economy after suddenly abandoning zero-COVID policies, both through private discussions after the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party and through public remarks at the World Economic Forum in Davos. However, to stimulate the economy, Chinese officials must stray from the tried-and-true strategy that calls for increasing exports and government investment stimulation. Public pessimism about the future might counteract the benefits of export growth and government stimulus, delaying economic recovery, if the issues of family underconsumption and slow income growth aren’t first addressed.

Over the past two decades, Chinese household spending has been a reliable growth engine, contributing close to 40% of Chinese GDP. The growing middle class in China was prepared to spend more on aspirational products because they believed their salaries would keep rising.

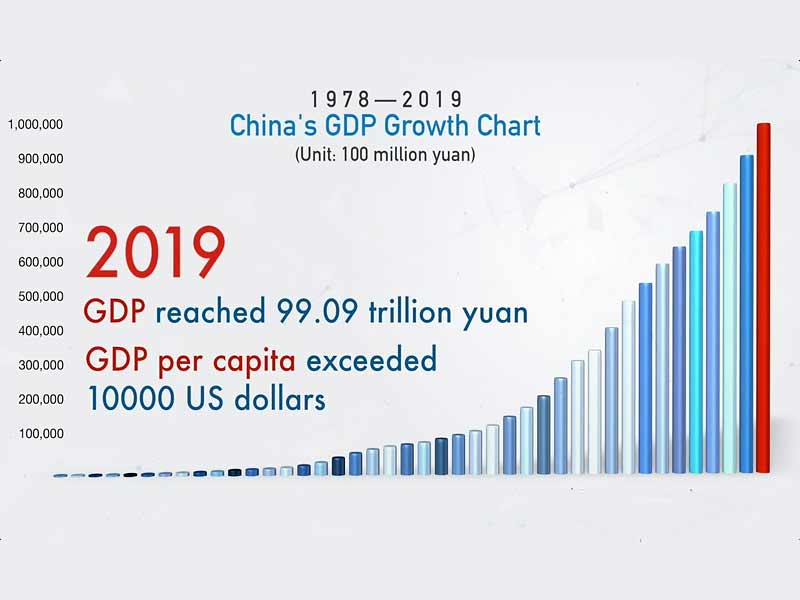

They were accurate: Between 2000 and 2019, the Chinese economy maintained an average annual GDP growth rate of 9%. According to findings from a 10-year countrywide poll of Chinese citizens, around 3.5 percent of Chinese households earned yearly incomes over 30,000 yuan (about $3,800) in 1997, according to a team of Gallup researchers. In just five years, this percentage rose to more than 12 percent. Researchers discovered a persistently high consumer demand for both necessities and luxuries.

Up until about 2017, there was a constant rise in household consumption. However, Chinese consumers witnessed the biggest decline in spending growth in a generation under President Xi Jinping’s second term, falling from 6.7 percent to 4 percent—significantly slower than GDP growth. Although the supply chain disruptions and widespread lockdowns have undoubtedly contributed to the decline in consumption, the regulatory crackdown on the tech sector by the Chinese government, coupled with China’s deteriorating external environment, has also fueled an unemployment crisis, particularly among young people.

Although the supply chain disruptions and widespread lockdowns have undoubtedly contributed to the decline in consumption, the regulatory crackdown on the tech sector by the Chinese government, coupled with China’s deteriorating external environment, has also fueled an unemployment crisis, particularly among young people.

Also read: New Zealand Economy Falls Into Recession

Since the COVID-19 epidemic, the difference between GDP growth and consumption growth has gotten wider. Before the epidemic, China’s real per capita consumption increased between 2013 and 2019 at an average annual rate of 6.38 percent, which was 59 basis points less than the 6.97 percent real GDP growth rate. From 2020 to 2022, this difference widened to 170 basis points as GDP growth fell dramatically to 4.5 percent while consumption fell to 2.8 percent, less than half its pre-pandemic level. Despite being the only global economy to enjoy growth in 2020, China’s household consumption witnessed its greatest fall in growth since the 1990s.

Even while the pandemic’s effects were severe, the fundamental cause of falling consumption throughout the Xi years has been slowing income growth. From 2013 to 2022, the average nominal annual family discretionary income growth rate decreased from an average rate of 11.04 percent between 2001 and 2012. Due to stagnant wage growth and greater economic insecurity than at any point before 1990, Chinese households are under the greatest material strain. China’s Consumer Confidence Index plunged to a record low of 85.5 points in November 2022.