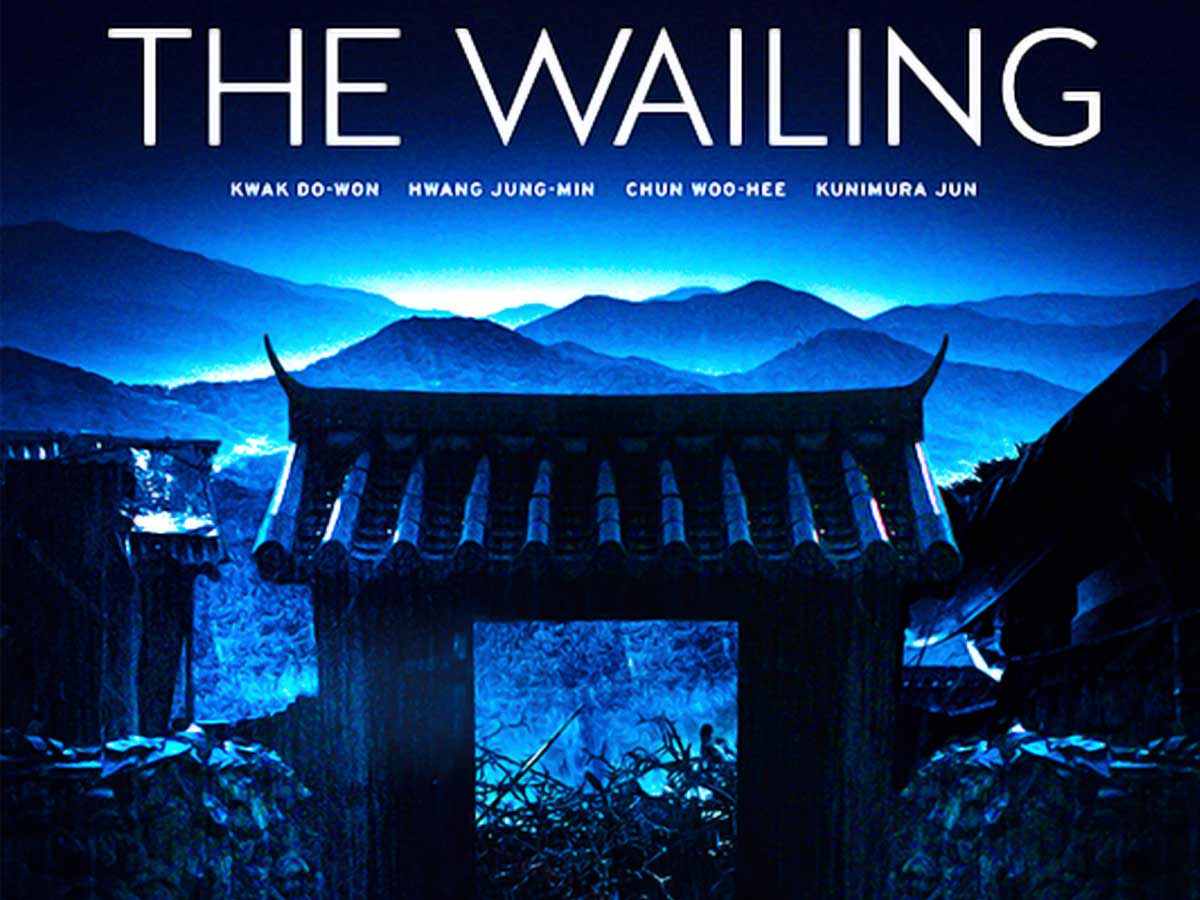

A ghost, a demon, a shaman, and a zombie-like viral virus have invaded an isolated mountain community in the new Korean horror film Gokseong (The Wailing). But none of these are the truly terrifying aspects.

Na Hong-jin made an international impression with his feature debut The Chaser in 2008, which he followed up with The Yellow Sea in 2010; both films are gloomy thrillers about lone, lost men caught up in events beyond their control.

On the surface, his third film, The Wailing, appears to be more of the same. Its Korean title relates to the name of the lonely, isolated mountain region at the center of the plot, yet its English title refers to the biblical plague-esque wave of violence, death, and sickness that appears out of nowhere.

The Wailing succeeds in combining a feeling of deep discomfort with visceral gore, buddy cop comedy, and a psychedelic combination of horror tropes — a concoction that generates, among other things, an unusual exorcism led by an impassioned Korean shaman. The film was a hit at Cannes last month, and anticipation has been building ever since.

The Wailing, on the other hand, has a lot going on, and despite its elegant ambiguity, brilliant direction, and the senseless and random violence that gives this film its dark center, it never quite escapes the weeds of its own swamp of suffering.

What’s good, terrible, and strange about The Wailing?

Good: the overpowering sense of tonal dread and ambiguity, enhanced by some stunning scenery.

The Wailing begins and ends in a flurry of insanity. Kwak Do-won plays the exhausted police sergeant Jong-Goo with a wonderful blend of tiredness, indecision, and terror. Jong-Goo, your usual bewildered cop, is perplexed, along with the rest of Gokseong’s local police department, by the commencement of a series of horribly violent and incomprehensible killings.

The killers all appear to be suffering from zombie-like symptoms, including a skin rash and boils, as well as appearing mad and monstrous and attempting to consume the flesh of the living. Local gossip blames the affliction on a newcomer, a mystery Japanese man who lives deep within the forested mountainside and is only known to the town’s residents as “the Jap.”

At first, Jong-Goo dismisses the rumors about this man and his evil supernatural powers as sheer ignorance. As the bodies pile up and Jong-Goo’s own daughter becomes afflicted by the strange curse, developing the strange rash as well as dark, violent desires, his reticence gives way to suspicion and desperation.

Na’s major talent as a director is his ability to blend distinct tonal periods without losing sight of the wider sense of dread that pervades his film. Kwak’s performance as Jong-Goo ranges from comedic incompetence as the fuddy-duddy local cop to barely hidden self-loathing to outright dread and rage as his distrust of the Japanese stranger and fear for his daughter intensifies. The sense of terror and urgency around the unknown curse that has come to his community is felt via each of these abrupt tonal swings.

The wailing single layer of suspense on tension, especially through the ratcheting up paranoia that each people of the town comes to feel for any and all outsiders.

The location of Gokseong has a pervading silence and sense of calm, and moments of blatant, wild craziness are frequently preceded by pictures of serene mountain panoramas whose lush, densely forested surroundings increasingly feel stifling and mysterious. This is a picture that is both beautiful and gruesome, as scenic as it is committed to strong visual interplays between darkness and light.

All the while, Gokseong’s story develops in fits and turns, each puzzle piece more perplexing than the previous. Is the town’s population being methodically poisoned with a chemical that turns them into frantic, savage killers? Is there a curse on them? Is it one or the other, and why? Na’s writing builds tension upon tension, particularly through the rising suspicion that each of the townspeople develops for all outsiders.

However, explanations are considerably more difficult to come by in this film than accusations. Horror aficionados looking for a plot whose finale fits in with all the aspects that came before it may be disappointed, but many more may be sucked into the heart of its darkness: the sense that terror has come to this town and there is no way out.

Also, Read House of the Dragon: Game of Thrones Legacy Revived Once Again

The disturbing xenophobia

The plot of The Wailing is largely centered on Jong-growing Goo’s obsession with the Japanese man, who is performed with a great blend of sadness and menacing ambiguity by renowned Japanese actor Jun Kunimura (Audition). Na has stated that his decision to cast a Japanese actor in the character of the outsider had “nothing to do with xenophobia,” and that his intention was to convey the irrational yet profound anxiety that can arise from the incapacity to connect with the person you fear.

Despite multiple voices warning Jong-Goo away from his fixation with the stranger, the plot rushes to a conclusion that may be understood as both confirming all of Jong-anxieties Goo’s and validating the Japanese stranger’s decision to isolate himself from his Korean neighbors in the first place.

Korea and Japan share centuries of historical enmity and continuing political difficulties, as well as significant animosity over Japanese colonialism of Korea in the early twentieth century and its still-controversial, the practice of enslaving numerous Korean residents to work as “comfort women.” Major tensions have recently flared over a chain of disputed islands in the South China Sea, and while the two countries have lately announced that relations have been mended, both Korea and Japan are notorious for their xenophobic tendencies, particularly toward each other.

The depiction of the villagers’ distrust of the lone Japanese character in The Wailing isn’t particularly subtle. And, based on how well The Wailing has performed at the box office in Korea, it clearly appeals to a large number of Koreans.

The anxiety that everything you’ve been taught to fear about strangers and outsiders is justified runs through The Wailing’s levels of solitude. Underneath the many unanswered concerns, it leaves us with in its pitch-black finale is the veiled message that failing to be skeptical of the Other may be your undoing, and that, eventually, dialogue with those you fear may be the last thing you desire.

This isn’t exactly a subversive story, and while The Wailing has plenty of conceptual complexities, they may not be enough to compensate for the film’s uncomfortable treatment of the film’s lone Japanese character.

Strange: a mingling of Catholicism, Korean shamanism, and the occult.

The highlight of The Wailing is a lengthy episode involving a dramatic shamanic ritual in an attempt to evict the demon believed to possess Jong-daughter.

Goo’s This rite occurs following Jong-Goo’s attempts to enlist the assistance of a reluctant deacon (a priest-in-training) and before a final visit to the town’s church causes a skeptical priest to reject Jong-Goo’s accusations that the Japanese stranger has unleashed evil onto the community. “The church can’t help you,” the priest adds before sending Jong-Goo on his way, a tragic decision that contributes to the film’s insane ending.

But if the church is unable to assist, the shaman — another mystery out-of-towner whom Jong-Goo’s family seeks out to assist in the rescue of his daughter — just makes matters worse with his rigorous exorcism process. The shaman’s ritual, shot with mesmerizing, feverish energy, is as bloody and horrifying as the gruesome acts that preceded it. The ritual’s eventual rupture at the hands of a distressed Jong-Goo feels as wrong as the ritual itself; it is at this point that we realize everyone in this story is completely lost, and that Gokseong is truly under the influence of esoteric supernatural forces beyond anyone’s control.

Finally, Na’s outstanding direction, elegant cinematography, and sense of aesthetics only serve to make the film’s supernatural elements feel rawer — but they also leave us unsure of what to believe. The Wailing hedges its bets on whether the type of devil, ghost, or zombie awaits us in the shadows, and eventually appears to throw up its hands and say, “Maybe all of them?” But, if that’s the scenario, the much-needed balance of cultural convergence is nowhere to be obtained; the shaman and also the priest never team up, and even the Korean cop, as well as the Japanese immigrant, never genuinely communicate.

A character is hit by lightning at one point in The Wailing’s first act. By the end of the film, this incident appears to be a kindness in comparison to the brutality that the rest of the town has endured. So, if The Wailing is an Old Testament story, it may be about the tower of Babel rather than Job’s personal tragedy: chaos commanded by the divine to test men’s fortitude.

However, it appears that whichever god is in charge is perhaps too impatient to wait for men to sort things out for themselves, and is eventually prepared to stand back and let the devil have his way with everything.