People have pondered the meaning of dreams and the science behind dreams. Early civilizations saw dreams as a conduit between our reality and the world of the gods. In fact, the Greeks and Romans believed that dreams had prophetic abilities. While there has always been a keen interest in the interpretation of human dreams, it wasn’t until the late nineteenth century that Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung advanced some of the most well-known modern theories of dreaming.

Freud’s thesis revolved around the concept of repressed longing, which holds that dreaming permits us to sort out unresolved, repressed wishes. Carl Jung (who studied under Freud) believed in the psychological significance of dreams but provided differing views concerning their meaning.

Other hypotheses have now emerged as a result of technological breakthroughs. The “activation-synthesis hypothesis,” which asserts that dreams are essentially electrical brain impulses that extract random thoughts and imagery from our memories, is a popular neurobiological theory of dreaming. According to the notion, humans build dream stories after they wake up in an attempt to make sense of it all.

Nonetheless, given the extensive recording of realistic Science behind dreams, as well as indirect experimental evidence that other mammals such as cats dream, evolutionary psychologists have suggested that dreaming has a purpose.

The “threat simulation theory,” in particular, proposes that dreaming should be viewed as an ancient biological defense mechanism that provided an evolutionary benefit due to its ability to repetitively simulate aggressive video events – enhancing the neuro-cognitive mechanisms essential for effective threat perception and avoidance.

As a result, several theories have been proposed throughout the years in an attempt to shed light on the mystery of human dreams, but strong tangible proof has remained mostly elusive until lately.

However, new research published in the Journal of Neuroscience gives intriguing insights into the mechanisms that underpin dreaming as well as the close link between our dreams and our memory. Cristina Marzano and her colleagues at the University of Rome have succeeded in describing how humans remember their dreams for the first time. Based on a distinctive pattern of brain waves, the scientists estimated the chance of good dream recall. To do this, the Italian study team asked 65 students to spend two nights consecutively in their research facility.

The pupils were left to sleep on the first night to get acquainted with the sound-proofed and temperature-controlled chambers. The researchers measured the students’ brain waves while they slept on the second night. There are four types of electrical brain waves in our brain: “delta,” “theta,” “alpha,” and “beta.”

Each represents a different frequency of pulsating electrical voltages, and they combine to generate electroencephalography (EEG). This technology was utilized by the Italian research team to measure the brain waves of participants during various stages of sleep. (There are five stages of sleep; the REM stage is when we dream the most and have the most intense dreams.)

The students were awakened at various times and asked to complete a journal describing whether or not they dreamed, how frequently they dreamed, and whether or not they could remember the substance of their dreams.

Also read : What is Life Science? Why should you Learn about It?

While prior research has shown that people are more likely to remember their dreams when awakened immediately after REM sleep, the present study explains why. Participants who had higher levels of low-frequency theta waves in their frontal lobes were more likely to remember their dreams.

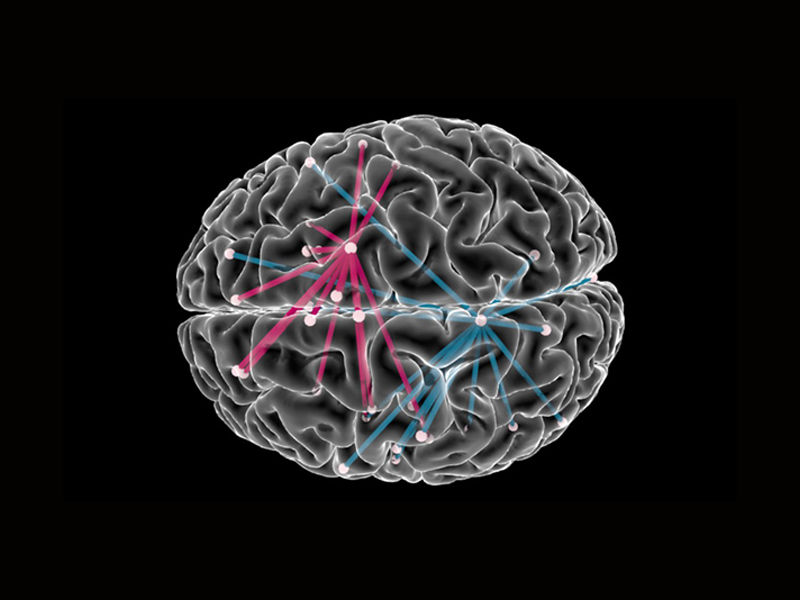

This discovery is intriguing because the increased frontal theta activity found by the researchers resembles the successful encoding and retrieval of autobiographical memories seen while we are awake. That is, it is the same electrical oscillations in the frontal brain that allow you to recall episodic memories (things that happened to you). Thus, these findings imply that the neurophysiological mechanisms we use while dreaming (and recalling dreams) are the same as those we use while waking to form and recover memories.

Another recent study by the same research team used the most advanced MRI techniques to analyze the relationship between dreaming and the role of deep-brain structures. The researchers discovered that vivid, strange, and emotionally strong dreams (the kind that people recall) are related to sections of the amygdala and hippocampus. While the amygdala is primarily responsible for emotional processing and memory, the hippocampus has been linked to crucial memory functions such as information consolidation from short-term to long-term memory.

Another recent study released by Matthew Walker and colleagues at the Sleep and Neuroimaging Lab at UC Berkeley discovered that a reduction in REM sleep (or less “dreaming”) impairs our ability to perceive complicated emotions in daily life – a key element of human social functioning. Scientists have also lately discovered wherein the brain dreaming is most likely to occur.

A relatively rare clinical illness known as “Charcot-Wilbrand Syndrome” has been linked to the loss of the ability to dream, among other neurological symptoms. However, it wasn’t until a few years ago that a patient reported losing her ability to dream despite experiencing virtually no other long-term neurological symptoms.

These latest discoveries, when taken together, present an essential tale regarding the underlying mechanism and possible purpose of dreaming.

Science behind dreams appear to aid in the processing of emotions by encoding and reconstructing memories of them. What we see and experience in our dreams may or may not be genuine, but the emotions associated with these experiences most emphatically are. Our dream stories simply attempt to remove the emotion from a certain experience by constructing a memory of it.

The emotion is no longer active in this manner. This technique is vital since not processing our emotions, especially negative ones, raises personal stress and anxiety. In fact, acute REM sleep deprivation is becoming more linked to the emergence of mental problems.