The samosa is much more than just a basic street food, despite what you may think.

It is a historical artifact and delicious proof that the march of globalization is nothing new.

When you bite into a samosa, the idea that identity is determined by national boundaries ought to crumble like the deep-fried crust.

Although it is now seen as a dish that is exclusively Indian, its history is far more nuanced and global than that.

Enjoy the sensation as your teeth delve into the center’s suppleness. Let the flavors envelop your palate.

What you are tasting is India’s history; it is the result of the dynamic forces of the massive migrations and exchanges that have built this nation.

The history of the samosa truly begins thousands of miles away, in the early civilizations that arose on the Persian plateau.

Although the exact moment that the first cooks formed pastry into the now-famous triangular shape is unknown, we do know that the name “sabotage” has Iranian roots.

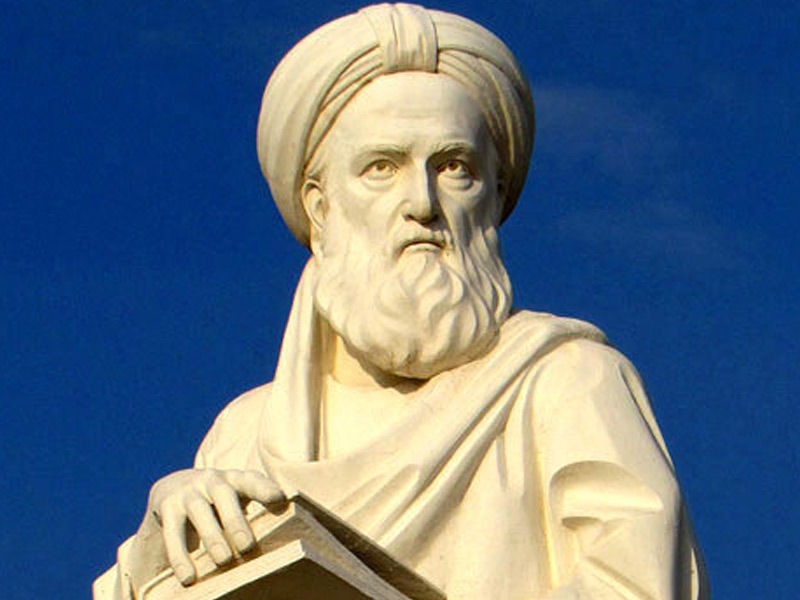

The Iranian historian Abul-Fazl Beyhaqi wrote about the samosa for the first time in literature in the eleventh century.

He talks of a delicate treat that was offered as a snack at the grand palaces of the powerful Ghaznavid dynasty. The delicate pastry was filled with ground beef, nuts, and dried fruit before being fried till crisp.

But, the samosa would change as it traveled with succeeding waves of migrant workers into India

It was transported to India by the same route that the Aryans had traveled more than 2,000 years prior: across Central Asia, over the formidable mountains of what is now Afghanistan, and finally into the fertile plains of India’s major rivers.

Later, the huge armies of the Mamluks, Tamerlane, and Mughals traveled similarly, aiding in the establishment of the great subcontinental empire that is now known as India.

And the samosa changed just like India did as a result of these waves of immigration.

It initially changed into something far less sophisticated.

One of the world’s foremost authorities on Indian cuisine, Professor Pushpesh Pant, characterizes it as “a rudimentary peasant meal” by the time it reached what is now Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

The once-courtly snack had evolved into a calorie-dense staple that was much heartier and larger—the kind of food a shepherd would carry out to the pastures with him.

The savory pastry was replaced with coarsely chopped goat or lamb that had been eked out with onions and simply salted. It still had its distinctive shape and was still cooked.

Samosas crossed the Hindu Kush’s cold passes and entered the Indian subcontinent throughout the ensuing decades.

Once in India, the samosa was adopted and adapted to local preferences, becoming the first fast food in history.

Samosas can be customized innumerably, and India added its spices by using coriander, pepper, caraway seeds, ginger, and more.

Vegetables frequently took the place of meat in the stuffing as well.

Because the modern Indian samosa is the result of yet another significant historical upheaval—the discovery of the New World—it was later to be used as the vehicle for other, much new meals

Nowadays, green chilies and potatoes are the two main ingredients in samosas; these items were originally brought to India by Portuguese traders in the 16th century.

And ever since, the samosa has developed further.

That is different everywhere you go in India.

While samosa makers compete for customers, samosas differ from region to region and even from shop to shop.

They can occasionally be monsters, packing an entire meal inside a single flaky pastry shell.

Samosas have made a comeback as a regal treat; they are often served as cocktail canapés at weddings and chic Delhi parties.

Even the wafer-thin pastry filled with mince and peas that the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta reports being served at the opulent banquets of Muhammad bin Tughlaq’s court in Delhi in the 14th century has survived in the “leukemia” of Hyderabad.

The addition of paneer, a fresh Indian cheese, to samosas is considered a must in Punjab, but it is frowned upon everywhere in India.

Nevertheless, not all samosas are savory; at least one Delhi

Even the methods used in cooking can differ.

Although the traditional samosa is still fried to a crisp, golden finish, you can occasionally get baked samosas for those watching their caloric intake.

Some cooks have tried steaming samosas, which is a mistake, according to Professor Pant. He contends that the flavors simply don’t come through correctly without the oil.

Naturally, the journey of the samosa did not finish in India. It returned to the outside world via new channels following centuries of improvement and modification here.

Together with shampoo, bungalows, verandas, pajamas, and other now-uniquely Indian innovations, the Brits adored the samosa and disseminated it throughout their vast empire.

And throughout the past few centuries, the Indian diaspora has dispersed all over the world, bringing samosas along with them.

Because of this, what was once a delectable treat for ancient Persian emperors is today enjoyed in almost every nation on Earth.

Thus, as you enjoy this delectable snack, keep in mind that samosas embody the spirit of India, which is adaptive, imaginative, tolerant, and multicultural, no matter where they were made or how they were filled.