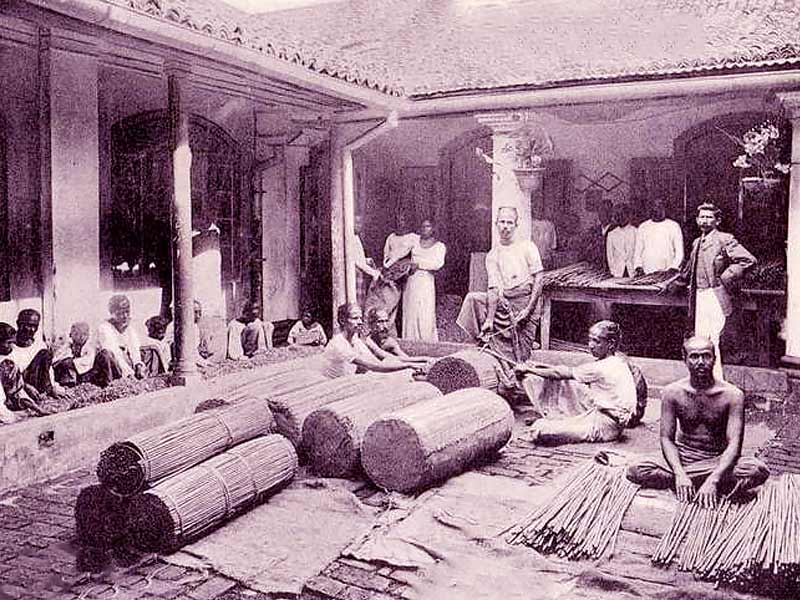

History of Sri lankan economy

Sri Lanka has a long history as a trading hub due to its location at the crossroads of east-west trade and irrigated agriculture in the hinterland, as evidenced by historical texts surviving on the island and accounts of foreign visitors. The island has irrigation reservoirs known as tanks that were built by ancient Kings beginning after the Indo-Aryan migration, many of which have survived to this day. They are part of an irrigation system that is linked to more modern structures.

Faxian (also Fa Hsien), a Chinese monk who traveled to India and Sri Lanka around 400 BC, writes about existing legends of merchants from other countries trading with native tribal peoples on the island prior to Indo-Aryan settlement. “The country that had no human inhabitants at first but was occupied by spirits and nagas (serpent worshipers) with whom merchants from various countries traded,” Faxian wrote in ‘A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms.’ He mentions precious stones and pearl fisheries, which are subject to a 30% king’s tax.

Past Decade of Sri Lankan Economy

Sri Lanka’s free-market economy was worth $84 billion in nominal GDP in 2019 and $296.959 billion in purchasing power parity (PPP). From 2003 to 2012, the country experienced annual growth of 6.4 percent, far outpacing its regional peers. This expansion was fueled by the expansion of non-tradable sectors, which the World Bank warned was both unsustainable and inequitable.

Since then, growth has slowed. Sri Lanka was reclassified as a lower middle-income country by the World Bank in 2019, with a per capita income of 13,620 PPP dollars or 3,852 (2019) nominal US dollars, down from upper middle-income status.

Sri Lanka has met the MDG target of halving extreme poverty and is on track to meet the majority of the other MDGs, outperforming other South Asian countries. In 2016, the poverty headcount index in Sri Lanka was 4.1 percent. Sri Lanka has begun to focus on long-term strategic and structural development challenges since the end of the three-decade-long Sri Lankan Civil War. It aspires to become an upper-middle-income country. Sri Lanka also faces challenges in terms of social inclusion, governance, and long-term viability.

Current Economic Crisis

Sri Lanka’s economy is in crisis, with usable foreign reserves of less than $50 million, according to the country’s finance minister.

Ali Sabry was speaking to Parliament after returning from talks with the International Monetary Fund in Sri Lanka. He stated that any IMF rescue program, including a rapid financing instrument needed to resolve urgent shortages of essential goods, would be contingent on debt restructuring negotiations with creditors and would take six months to implement.

Sri Lankan economic crisis is worst and the country is on the verge of bankruptcy, and payments on its foreign loans have been halted. Its economic woes have precipitated a political crisis, with the government facing protests and a no-confidence vote in Parliament.

Also read: 5 Industries That Are Reeling Under Pressure Due To Global Economic Crisis

The country is expected to repay $7 billion of the $25 billion in foreign loans due by 2026 this year.

The opposition United People’s Force accuses the government of failing to fulfill its constitutional duty to provide a decent standard of living. It accuses top government officials of excessive money printing, harming farm production by prohibiting chemical fertilizers in order to make production fully organic and reduce import costs, failing to order COVID-19 vaccines on time, and buying them later at higher prices.

A date for a vote on the no-confidence motion has not yet been set.

The foreign currency crisis has limited imports and resulted in severe shortages of essential goods such as gasoline, cooking gas, medicine, and food. People must queue for hours to purchase what they can, and many return home with little, if any, of what they sought.

The foreign currency crisis has limited imports and resulted in severe shortages of essential goods such as gasoline, cooking gas, medicine, and food. People must queue for hours to purchase what they can, and many return home with little, if any, of what they sought.

Protests have erupted calling for the resignations of Mahinda Rajapaksa, the leader of an influential clan that has ruled for the majority of the last two decades, and his younger brother, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

“There is a serious risk in front of all of us,” Sabri explained. He stated that Sri Lanka’s reserves stood at $7.6 billion at the end of 2019 and would fall to $5.7 billion by the end of 2020 as payments outpaced foreign currency inflows due to the pandemic.

So far, the Rajapaksa brothers have resisted calls to resign, despite the fact that three other Rajapaksas, three of whom are lawmakers, resigned from Cabinet positions in mid-April.

Sri Lanka, according to Sabri, is in the process of appointing legal and financial advisers to help with negotiations on restructuring its foreign debt.

“We are in the midst of an economic crisis.” A political crisis has resulted from the economic crisis. “It is critical to resolving the political crisis before addressing the economic crisis,” Sabri said.