The one-of-a-kind Voynich Manuscript, full of exotic images and written in an unknown language, has so far perplexed everyone who has attempted to decipher its secrets. What does it imply, and who wrote it? Spencer Mizen tells the story of his effort to explain the inexplicable. We’ve placed a man on the Moon, developed general relativity theory, split the atom — the list of advances in making the impossible possible is endless. Isn’t it true that humanity can do pretty much everything it sets its mind to?

Perhaps not much at all. For there is a book at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University in the United States that refuses to succumb to our unquenchable desire for knowledge and explanation.

Scholars could not decipher the obscure inscription for generations. Their most recent attempts include computer analysis in search of new insights into the mediaeval mystery.

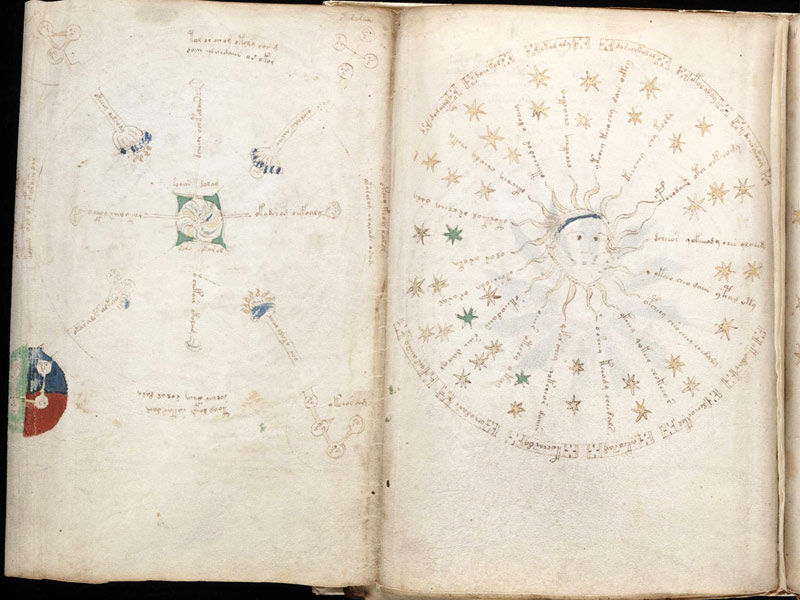

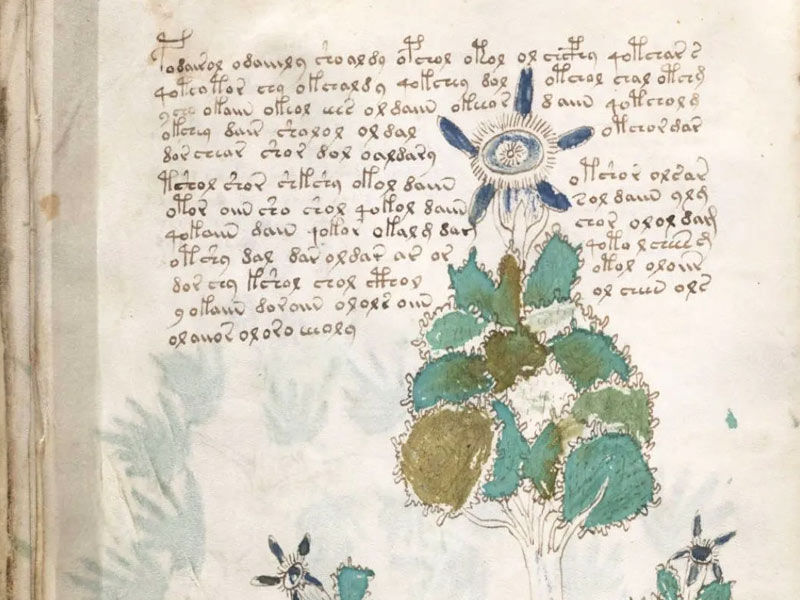

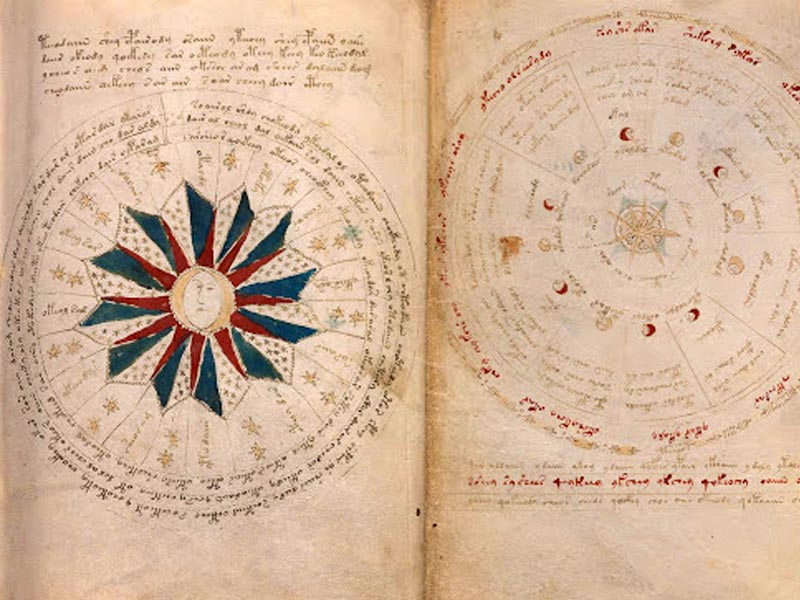

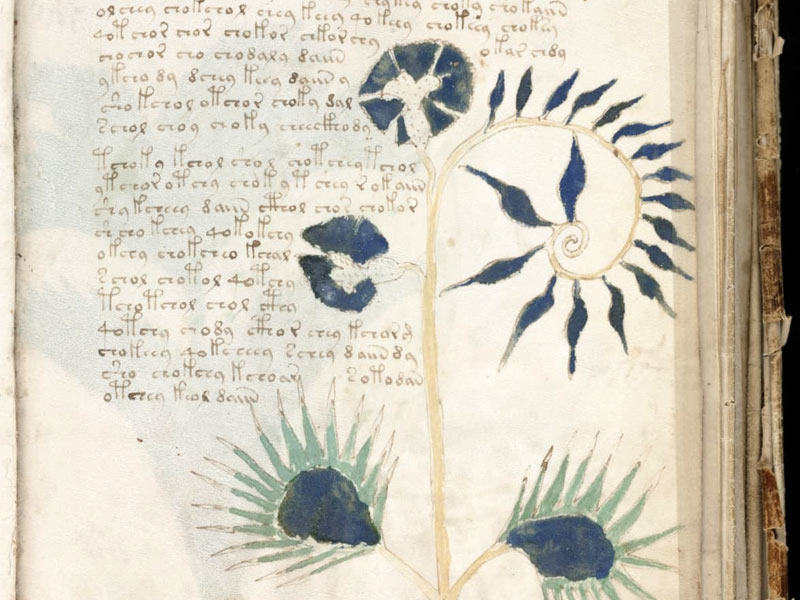

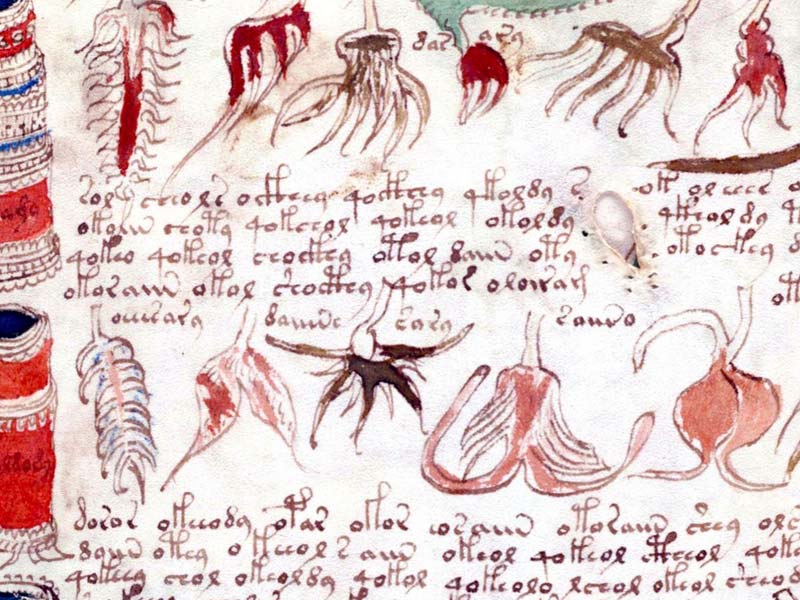

For generations, researchers and decipherers have been baffled by the 15th-century VOYNICH MANUSCRIPT. Hundreds of vivid pictures of flora, astrological patterns, and nude female figures swimming in ingeniously plumbed pools of green water adorn its 200-odd pages. Even stranger, the document is written in no recognised script or language. If it’s written in code, no one has broken it, despite several attempts.

The manuscript was named after Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish-born antiquarian who purchased and promoted it in the early twentieth century.

- Some researchers believe the text is nonsense, and the document is a complex deception.

- Others have suggested that the underlying language is Latin, a Romance language, or Hebrew.

- In 2018, a pair of scholars suggested the document was created by the ancient Aztecs, given the apparent closeness of some of the scroll’s plant images to the flora of Central America.

None of these assertions have received popular support.

The Voynich manuscript is presently housed at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Leaf through the manuscript’s 240 gorgeously drawn vellum pages and you’ll quickly understand why it has captivated so many people for so long. Its pages are filled with a plethora of fanciful drawings — the kind you’d expect to see in a dream rather than on the pages of a centuries-old manuscript. There are floating castles, disembodied heads, flowers that have no resemblance to anything on Earth, odd animals that resemble jellyfish, and a plethora of naked ladies soaking in water.

It is the book that has perplexed the academic world’s greater good. It has proven completely indecipherable, written in an unfamiliar script with an alphabet that exists nowhere else other than on the pages of this text.

The Voynich Manuscript has baffled brilliant wartime cryptologists such as Alan Turing, FBI operatives (presumably worried the manuscript may contain communist propaganda), respected medievalists, mathematic and scientific researchers, experienced linguists, and others. Without success, the talented William Friedman – chief cryptoanalyst in the US Army’s Signal Intelligence Service–spent 30 years trying to uncover the secrets.

Wilfrid Voynich, who was he?

Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish-Lithuanian book sales associate with revolutionary sympathies and distinguished contacts, was at the heart of this wordy whodunit.

To say he had a colourful life would be an understatement. Born in what is now known as Lithuania in 1865, he was apprehended for his socialist activities and detained in Siberia before fleeing to London. There, he opened a used bookstore that was frequented by the man who would become Sydney Reilly, the ‘Ace of Spies.’

Also Read, Bermuda Triangle: The Mystery Unraveled

However, it was in a Jesuit seminary outside Rome in 1912, during a book-buying expedition, that Voynich allegedly discovered the manuscript that would bear his name. Voynich, it appears, realised right away that he had stumbled across something quite exceptional.

A letter appended to the manuscript, not likely fueling Voynich’s imagination purported to give some insight on the document’s background. The communication, written by imperial physician Johannes Marcus Marci in 1665, stated that the document originally belonged to Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, who reigned from 1576 to 1612. Its second owner was supposedly a Prague-based alchemist named Georg Baresch, who “devoted unflagging toil” to interpreting the writing and “relinquished hope only with his life,” according to Marci.

The manuscript was later gained by Marci, who gave it to a Jesuit scholar named Athanasius Kircher in the expectation that he would succeed where Baresch had failed.

Who was the author of the Voynich Manuscript?

According to Marci’s letter, the text might have been created by the 13th-century philosopher and alchemist Roger Bacon. Voynich dubbed his find the “Roger Bacon cypher text.” Is the case closed? Not. A slew of people have been proposed as potential writers.

Voynichologists have claimed that the text’s origins may be traced back to languages ranging from Old Cornish and Old Turkish to the Aztec language, Nahuatl.

Others have supported the hypothesis that the poem was created by Queen Elizabeth I’s astronomer, John Dee, and the alchemist Edward Kelley as an elaborate Tudor prank. But, as the centennial of Voynich’s discovery of the book neared, science poured cold water on the claims.

Radiocarbon dating revealed in 2009 that the vellum on which the text and illustrations were produced dated to the 15th century–most likely between 1404 and 1438 — a century before the Elizabethan grandees were in their heyday. The document appears to be a mediaeval enigma rather than a Tudor one.

If Voynichologists thought that radiocarbon dating would help to settle the debate over the book’s provenance, they were misled. When historical scholar Nicholas Gibbs announced the document was a women’s health guide in 2017, he sparked considerable controversy.

A reference book of selected treatments drawn from standard treatises of the mediaeval period, an instruction manual for the health and well-being of society’s more affluent ladies.

Gibbs’ reasoning was based on pictures of bathing ladies and the constant usage of Zodiac signs, both of which were commonly used in medical treatises in mediaeval Europe. While he published his idea in the highly regarded Times Literary Supplement, it did not receive a warm welcome.

The Voynich Manuscript has been decrypted?

In May 2019, the Voynich Manuscript was thrust back into the spotlight after an academic claimed he had achieved where others had failed and successfully interpreted the strange text.

Cheshire concluded the book was a “compendium of material on herbal cures, therapeutic baths, and astrological readings” collected by Dominican nuns as a reference for Maria of Castile, Queen of Aragon — Catherine of Aragon’s great aunt. Cheshire claimed the book was composed in the first part of the 15th century in proto-Romance, a now-lost language.

Cheshire is far from the only expert who believes the Voynich Manuscript was written in what was once a live, spoken language rather than code or meaningless gobbledegook. Many say that it has all the qualities of a true language, with specific words, for example, only appearing alongside particular visuals.

This didn’t save Cheshire’s hypothesis from confronting a response as vehement as the one levelled at Nicholas Gibbs. Fagin Davis led the battle once more, calling Cheshire’s article “simply another ambitious, cyclical, self-fulfilling bullshit.”

Is it possible that the Voynich Manuscript is a forgery?

Another potential answer to the enigma seems to have died. With the book continuing to perplex academics and so many dead ends reached, must we simply conclude that the Voynich Manuscript will never reveal its secrets? Could the solution to this riddle be there in front of us — in the guy’s form for whom it is named?

For decades, there has been speculation that this ancient text was a 20th-century counterfeit devised and executed brilliantly by none other than Wilfrid Voynich himself.

But, you may wonder, what about the radiocarbon dating that dated the document to the early to-mid 1400s? The vellum is from that era. However, there are rumours that Voynich purchased an enormous quantity of vellum and then duplicated the mediaeval inks and colours that adorn that vellum himself.

Also Read, 10 Unsolved Mysteries of India that you Might not know

Is this a forgery or a genuine piece of mediaeval literature? Is this the home of a vanished tongue or a collection of useless babble? One thing is certain: the Voynich Manuscript is a mystery that never ends. And, if the last several years of intrigue, claim, counter-claim, and denial are any sign, it will continue to give for quite some time.