“Myth serves two purposes,” stated poet and scholar Robert Graves in 1955. “The first is to respond to difficult inquiries from youngsters, such as ‘Who built the world?’ What will happen at the end? What was the name of the first man? ‘What happens to souls after death?’ … The second role of myth is to legitimize an existing social structure and explain ancient rituals and customs.” Stories about gods and goddesses, heroes, and monsters were an essential element of everyday life in ancient Greece. They described everything from religious ceremonies to the weather, and they provided meaning to the world they observed.

Sources for Greek Mythology

There is no original source in Greek mythology that introduces all of the myths’ characters and storylines, as there is in the Christian Bible or the Hindu Vedas. Instead, the oldest Greek myths were part of an oral tradition that originated in the Bronze Age. Their plots and themes emerged gradually in the archaic and classical periods’ written literature. Homer’s epics from the eighth century BC, the Iliad, and the Odyssey, for example, portray the narrative of the (mythical) Trojan War as both a divine and a human battle.

They don’t bother introducing the gods and goddesses as their major protagonists because readers and listeners are already familiar with them.

Did you know that? Many consumer goods have names derived from Greek mythology. Nike footwear, for example, is named after the goddess of victory. In contrast, the website Amazon.com is named after a race of mythological female warriors. Many high schools, collegiate, and professional sports teams (such as the Titans, Spartans, and Trojans) draw their names from mythical origins.

The poet Hesiod’s Theogony, written around 700 BC, provided the earliest recorded cosmogony, or genesis tale, of Greek mythology. The Theogony narrates the tale of the universe’s evolution from nothingness (Chaos, a primal vacuum) to existence. It includes a complex family tree of elements, gods, and goddesses derived from Chaos, including Gaia (Earth), Ouranos (Sky), Pontos (Sea), and Tartaros (the Underworld).

Later Greek poets and painters drew on and expanded on these sources in their own work. Mythological people and events, for example, exist in Aeschylus’, Sophocles’, and Euripides’ 5th-century plays and Pindar’s lyric poetry.

The ancient myths and tales were collected for modern audiences by writers such as the 2nd-century BC Greek mythographer Apollodorus of Athens and the 1st-century BC Roman historian Gaius Julius Hyginus.

Archaeological findings

The discovery of the Mycenaean civilization by Heinrich Schliemann, a 19th-century German amateur archaeologist, and the discovery of the Minoan civilization in Crete by Sir Arthur Evans, a 20th-century English archaeologist, is critical to understanding the development of myth and ritual in the Greek world in the twenty-first century. Such findings provide light on features of Minoan society from around 2200 to 1450 BCE and Mycenaean civilization from approximately 1600 to 1200 BCE; both eras were followed by a Dark Age that lasted until approximately 800 BCE.

Unfortunately, because the Linear B script was primarily employed to record inventories, the evidence for myth and ritual at Mycenaean and Minoan sites is essentially enormous.

Geometric patterns on ceramics from the eighth century BCE show events from the Trojan cycle and Heracles’ exploits. However, the severe formality of the style makes much of the identification impossible, and there is little inscriptional evidence to aid academics in identification and interpretation.

Homeric and other mythical events complement the extant literary material in the subsequent Archaic (c. 750–c. 500 BCE), Classical (c. 480–323 BCE), and Hellenistic periods.

Let’s Begin

Greek mythology is the collection of tales about the gods, heroes, and rites of the ancient Greeks. The most critical Greeks, such as the philosopher Plato in the 5th–4th century BCE, understood that the stories contained a significant element of fabrication. In general, though, the Greeks’ common piety regarded the myths as accurate facts. Greek mythology has since had a significant impact on the arts and literature of Western civilization, which inherited much of Greek culture.

Although people from all countries, eras, and stages of civilization have created myths to explain the existence and workings of natural phenomena, recount the exploits of gods or heroes, or justify social or political institutions, the Greek myths have remained unrivaled in the Western world as sources of imaginative and appealing ideas. Poets and artists have drawn inspiration from Greek mythology from antiquity to the present day, discovering modern importance and relevance in Classical mythical subjects.

Mythical forms in Greek mythology

Distinguishing between myth, legend, and folktale can be beneficial, but keep in mind that the Greeks did not do so.

Myths in religion

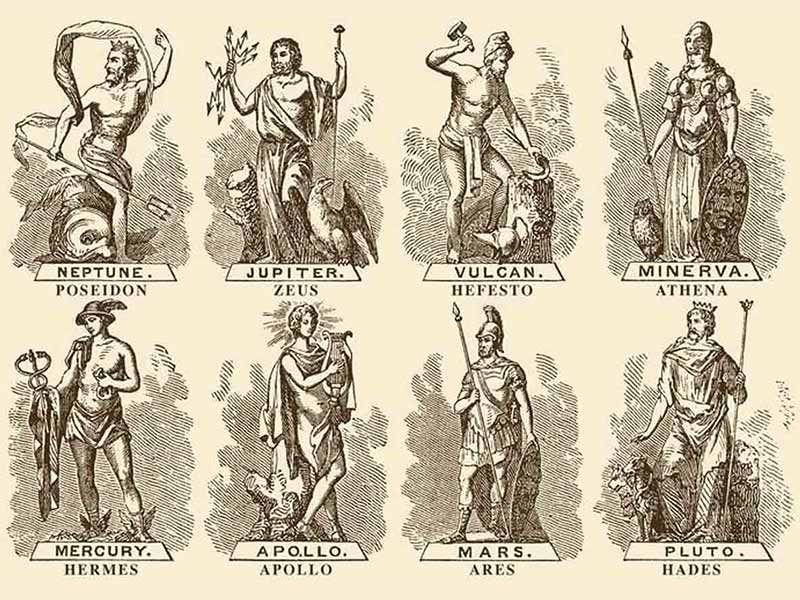

Greek mythology and mythological stories are concerned with gods or heroes in their more serious elements or associated with ritual. They comprise cosmogonical stories about the creation of the gods and the universe from Chaos, the successions of divine rulers, and the internecine battles that resulted in Zeus, the reigning deity of Olympus’ dominance.

They also provide a lengthy account of Zeus’s liaisons with gods and human women, which generally culminated in the birth of younger deities and heroes. The narrative of Athena’s motherless birth implies her unique position. At the same time, the stories of Apollo explain that god’s sacred affiliations, detail his spectacular conquests against monsters and giants, and emphasize his jealousy and the perils inherent in everlasting relationships.

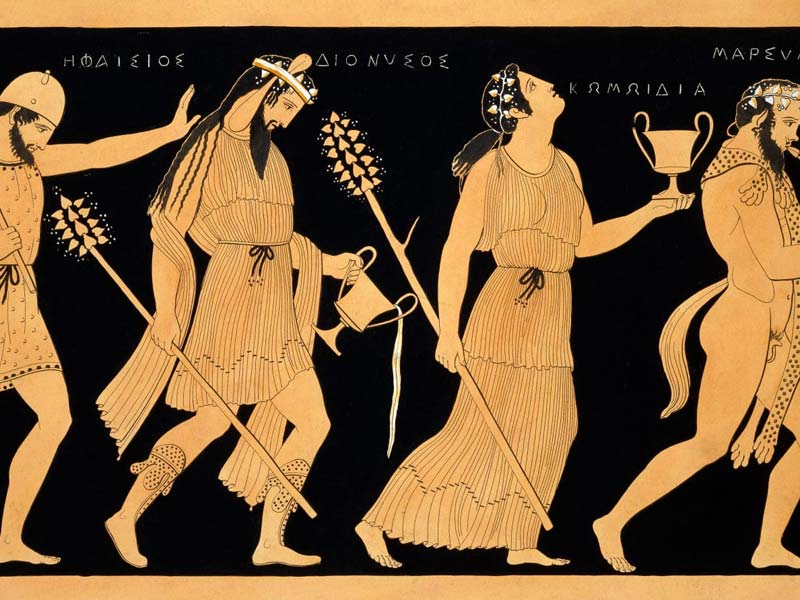

Myths of Dionysus, on the other hand, show the hatred engendered by a new faith.

Some stories are intimately linked with rituals, such as the tale of the Curetes, Zeus’ attendants, clashing their swords and silencing the baby Zeus’ screams, or Hera’s annual restoration of her virginity by bathing in the spring Canathus. Some stories about heroes and heroines are also religious in nature. The story of creation and moral fall is part of the Four Ages myth. The following flood destruction of mankind and the regeneration of humans from stones is based in part on folklore.

Legends

Legends (or sagas) were thought to be quasi-historical, while myths represent divine or eternal truths. As a result, legendary events in epics, like the Trojan War, were widely believed to have occurred, and heroes and heroines were thought to have lived.

Earlier sagas, like the Argonauts’ trip, were accepted similarly. Most Greek mythology have been enriched with folktales and fiction, although some do have a historical basis. Such are the stories of more than one sacking of Troy, which are corroborated by archaeological evidence, and Heracles’ labors, which may imply Mycenaean feudalism.

Again, the tale of the Minotaur (a half-human creature and half bull) may have originated from exaggerated stories of bull jumping in ancient Crete.

In another kind of tale, terrible acts, such as attempting to rape a goddess, excessively misleading the gods by incriminating them in crime, or claiming their prerogatives, were punished by eternal agony in the underworld. Legend also describes the repercussions of societal crimes such as murder or incest. Legends were often used to legitimize existing political institutions or to support territorial claims.

Folktales

Folktales, which consist of popular repeating themes and are recounted for entertainment, unavoidably made their way into Greek mythology. Such is the subject of missing people, whether it’s a spouse, wife, or child found or retrieved after a long and adventurous trip. Orpheus, Heracles, Odysseus, and Theseus all made journeys to the country of the dead. The triumph of the tiny man through ingenuity over unfathomable odds, the exploits of the superhuman, or the long-delayed victory over foes are still as popular with modern writers as they were with the Greeks.

The effective foiling of harsh sires and stepmothers, the rescuing of princesses from monsters, and temporary forgetfulness at a critical juncture are all common motifs in Greek myth. Another popular folktale element is recognition by symbols, such as Odysseus’ scar or idiosyncrasies of attire. The babes-in-the-woods concept of child exposure and eventual recovery may also be found in Greek mythology. The Greeks, on the other hand, were well aware that child exposure was a regular practice.

Mythological types in Greek mythology

Also Read, Most Fascinating Greek Myths

Myths about origin

Myths of origin are an attempt to make the cosmos understandable in human terms. The Greek creation myths and cosmos views were more methodical and precise than those of other ancient peoples. However, because the Greeks enriched the myths with folktales and fiction presented for their own reason, their own artistry acts as a barrier to interpretation. Thus, even though the goal of Hesiod’s Theogony is to chronicle Zeus’ supremacy.

The addition of common themes such as generational conflict, the riddle of a woman (Pandora), the exploits of the benign trickster (Prometheus), and battles against great creatures or monsters such as the Titans heightens the intrigue of an epic tale.

According to Hesiod, the Gap (Chaos), Earth (Gaea), the Abyss (Tartarus), and Love were the first divine creatures to exist (Eros). The creation process began when Gaea was forcibly separated from her adoring lover Heaven (Uranus) for her children to be created.

However, the crudity is alleviated in a typical Greek manner by Uranus and Gaea’s amicable partnership after their divorce on a scheme to save Zeus from the same Cronus, his cannibalistic sire.

The Earth was regarded as a flat disk adrift on the river of the Ocean in Greek cosmological ideas. At night, the Sun (Helios) flew around the Earth in a golden bowl, traversing the skies like a charioteer. Natural cracks were often believed to be gates to Hades, the underworld dwelling of the dead.

Myths of the World’s Ages

Greek myths appear to have been susceptible to critique and change from a very early time on the grounds of morality or distortion of known facts. In the Works and Days, Hesiod used a Four Ages (or Races) scheme: Golden, Silver, Bronze, and Iron.

Although “Race” is a more appropriate translation, “Golden Age” has grown so common in English that both phrases should be stated. These races or centuries are independent creations of the gods, with the Golden Age belonging to Cronus’ rule and the succeeding races being Zeus’ creation. Those who lived in the Golden Age never grew old, were free of toil and spent their time laughing and eating.

When they died, they became Earth’s guardian spirits.

Hesiod did not explain why the Golden Age ended, but it was followed by the Silver Age. After abnormally lengthy infancy, the men of the Silver Age began to act arrogantly and ignored the gods. As a result, Zeus imprisoned them on the Earth, where they became ghosts among the dead.

Zeus then created the men of the Bronze Age, beings of violence who died due to mutual destruction. The Age (or Race) of Heroes is interpolated at this point by the poet. In the interests of history, he undermines the myth’s symmetry: what is now known as the Minoan-Mycenaean period was widely thought to be a good time to live in antiquity.

The poet himself had the misfortune to live during the Iron Age, which was the antithesis of the Golden Age. Even yet, he felt that there would come a day when children would be born old, and there would be no remedy against the general moral deterioration. Pandora’s hasty haste in opening the fateful jar explained the presence of evil.

The gods’ myths

Myths about the gods detailed their births, victories against monsters or competitors, love relationships, unique powers, or links to a cultic location or rite. Because these powers tended to be broad, the stories of many gods were similarly complicated. Thus, the Homeric Hymns to Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, and to the Delian and Pythian Apollo explain how these goddesses were linked with Eleusis, Delos, and Delphi, respectively. Similarly, tales about Athena, the patroness of Athens, emphasize the goddess’ love of fighting and her devotion to heroes and the city of Athens.

Those about Hermes (the deity’s messenger), Aphrodite (goddess of love), and Dionysus highlight Hermes’ inclinations as a god of thieves, Aphrodite’s lovemaking, and Dionysus’ relationship with alcohol, frenzy, miracles, and even ritual death. Poseidon (god of the sea) was notably atavistic in that his connection with Earth, as well as his equestrian exploits, appear to harken back to his pre-marine position as a horse or earthquake deity.

Many myths are dismissed as insignificant and frivolous. Yet, this assessment is based on the hidden premise that any supernatural behavior that appears improper for a large religion must have appeared ridiculous and fictional to the Greeks. Homer scarcely mentions the judgment of Paris, although he was well aware of the far-reaching implications for Troy of Aphrodite’s favor and Hera and Athena’s fierce hatred, which the “judgment of Paris” was written to explain.

As time passed, a slew of smaller myths grew to augment the older and more real ones. Thus, Homer and Hesiod overlooked Apollo’s affections, which explained why the bay (or laurel) became Apollo’s holy tree and how he came to father Asclepius, a curing deity. Similarly, tales explained the appearance of the cuckoo on Hera’s scepter at Hermione and the creation of the panpipe. Such etiological stories thrived during the Hellenistic era, while real instances are harder to find in earlier times.

Myths of heroes

Hero myths included aspects from folklore, legend, and fiction. The Argonauts’ narrative, for example, is very intricate and incorporates aspects of folklore and fiction. Episodes in the Trojan cycle, such as the departure of the Greek fleet from Aulis or Theseus’ Cretan voyage and death on Scyros, may have roots in Minoan-Mycenaean legends. On the other hand, the events recounted in the Iliad are likely due to Homer’s inventiveness rather than actual tradition. Even legendary heroes such as Achilles, Hector, and Diomedes are mainly fictitious but based on mythical predecessors.

The Odyssey is a good example of folktales being imported wholesale into epic. All of the most well-known Greek hero myths, such as Heracles’ labors and the exploits of Perseus, Cadmus, Pelops, or Oedipus, are based on folktales rather than mythology.

Certain heroes, such as Heracles, the Dioscuri (the twins’ Castor and Pollux), Amphiaraus (one of the Argonauts), and Hyacinthus (a youngster whom Apollo adored and inadvertently killed), may be considered both folklore and religious myth. Thus, while Heracles, a Tiryns man, may have been a historical figure at one time, the story of his death on Oeta and his elevation to full deity is inextricably tied with a cult.

Heracles’ fame throughout time was responsible for linking his narrative to the Argonauts, an earlier raid on Troy, and Theban myth. Similarly, the Dioscuri’s adventures are typical of heroes: fighting, kidnapping women, and cattle rustling. Following their death, they spent six months alternating beneath the Earth and above, implying that their devotion, like that of Persephone, was associated with fertility or seasonal change.

To Know about the Greek Gods, Click Here