Gandhi Godse — Ek Yudh by Rajkumar Santoshi begins with a lengthy disclaimer. According to the producers of the hypothetical play Godse@Gandhi.com, they attempted to depict the philosophies of these two personalities in an ‘unbiased’ manner. But this weird parallelism isn’t the drama’s only notable characteristic. Because its neediness and desperation are more obvious.

Archival imagery from the Partition appears in the opening titles, including burning buildings, injured people, and dead bodies. The background score booms, simulating the ferocity of roaring masses. This aesthetic is maintained throughout, with the inclusion of new elements such as persistent cinematographic excess (showing four reaction shots, for example, when one would suffice), loud performances, and newspaper clippings.

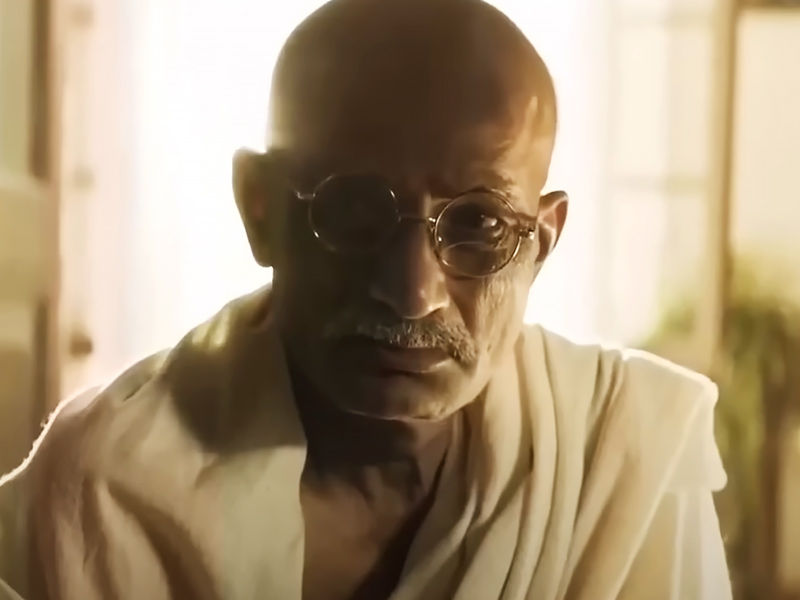

The film is divided into three sections: from Indian independence to Godse killing Gandhi, the following several months of their life, and their interactions in jail. The first section is intercut with two segments: Gandhi (Deepak Antani), who is concerned about the communal fire in the country, and Godse (Chinmay Mandlekar), who is upset about the fate of Hindus. Despite remaining fair and sympathetic to Gandhi, the film makes several weird conflations – and takes incredible dramatic license – in presenting Godse.

The play portrays him as an ‘angry Hindu,’ and his fury is used to broad brush most, if not all, Hindus. “Gandhi hai hai,” the Hindu refugee camp shouts. Another lengthy video depicts Godse seeing the ‘forceful’ evacuation of Hindus (who had taken over the Muslims’ homes), prompting us to sympathize with him. One dramatic scenario after another portrays Gandhi as ‘anti-Hindu,’ virtually justifying Godse’s actions. How is the killer portrayed in the film? Angry and insane, insane and angry. Throughout the film, Godse, the original bhakt, yaps about the same few things: Hindu, Hindutva, Akhand Bharat, and the Rs 55 crore loan to Pakistan.

This film is so dedicated to Centrism 101 that it left me perplexed for a while. Because Godse comes out as unfair and petty in numerous instances, as well as insecure and threatening. But I kept wondering, ‘Is the film aware of it?’

This perplexity is exacerbated when the film gently attempts to portray Godse as good, such as his not violating Gandhi’s trust (when he insists on meeting his killer unarmed).

Its screenwriting blunders are just as bad. The middle section, which reimagines Gandhi and Godse’s life after January 30, 1948, is a masterpiece in sloppy filmmaking. One useless subplot follows another. Sushma (Tanisha Santoshi) is a young woman who joins Gandhi to practice “desh sewa” in one of them. She’s dating a supportive man, but Gandhi sees love as “vikaar [a disease]”. Gandhi first opposes the alliance, then turns hostile and dictatorial: “It’s either your relationship or the country,” he tells her. In other news, Gandhi wishes to disband Congress; the party disagrees, and Gandhi departs.

The storyline focusing on Gram Swarajya has some potential, but it, too, is undone by lackluster execution. We have three extended scenes centered on attempted rape, a feud between the Indian government and the Adivasis, and the villagers organizing their own police force, all of which are presented by the media and leaders as Gandhi becoming the court, government, and police. Gandhi is imprisoned for being a “desh drohi,” and this is where he meets his enemy. Godse, on the other hand, maintains his anti-Gandhi ranting. Until the first 70 minutes, you don’t learn anything new about either of them that hasn’t already been documented in innumerable books, articles, and documentaries.

The last confrontation is where you’ll find anything new. Gandhi inquires about Godse’s vision for the country. Godse gestures to an ‘Akhand Bharat’ map on the jail’s wall. Gandhi believes that forming a country requires gaining the trust of the people. “Tum bina dekhe, bina jaane pyaar karte ho [You love something without seeing or knowing it]?” he says to Godse. These passages startled and touched me. But the greatest sentences come shortly after: Gandhi tells Godse “you’re making Hindustan tiny”, followed by “you’re making Hinduism little”. Gandhi is horrified when he queries Godse about why he didn’t even hurl a stone at the Britishers.

Also, Read Class: An Engrossing And Illuminating Presentation About Privilege

This little segment is undoubtedly the greatest section of the film. Not only because of what it says but also because of how it says it: these talks have a Gandhian air to them, with disagreement expressed via contemplation rather than reprimand. But sitting through a 110-minute film for a five-minute interaction is a bit much. Because this narrative is not literally nor figuratively profound, Gandhi Godse — Ek Yudh might have been a fascinating (though not remarkable) 20-minute short. Furthermore, its weird declaration of a reformed Godse in the end – who hasn’t modified his essential ideas – adds to the confusion. You may produce a film on opposing viewpoints, but you must still have your own point of view. I’m not sure what this picture believes in.