We rank every Oscar winner’s character, from WWII heroes to hired killers, Forrest Gump to Fred Rogers.

When contacted by the New York Times to comment on Tom Hanks, producer Brian Grazer recounted a conversation with several colleagues about a project they were working on in the mid-’90s. They intended to recount the narrative of Apollo 13’s risky, abortive voyage to the moon; common reason and studio suits demanded that they cast not just a star but the type of matinée-idol. Action-movie poster boy who would have people roaring in the aisles and spilling their popcorn.

Grazer listened to everyone’s opinions before asking, “Who do the people of the globe want to preserve the most?” Tom Hanks was the unanimous choice.

For decades, the 63-year-old actor has been Hollywood’s Mr. Nice Guy, one half of a showbiz power couple, and the sort of real-life Good Samaritan who inspires by example. When he disclosed on Instagram that he and his wife Rita Wilson had acquired the coronavirus while filming Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis biography, it not only made the epidemic feel horrifyingly real, but it also became a national drama. Does America’s father have COVID-19?

No way, Tom! And when they eventually returned to Los Angeles after inching their way back to health, surprise-hosting a remote SNL show, and giving a graduating address via Zoom, you could almost hear a communal sigh of relief. You can’t leave yet, Tom. We still require your assistance.

He’s such a beloved figure, in fact, that it’s easy to forget the multiple Oscar winner is more than the sum of his sweet attributes and isn’t just a movie star. The kind of marquee name you go to for the same comfortable screen qualities time and again — but also a hell of a versatile performer.

And he’s such an icon of contemporary American cinema that it’s easy to forget he wasn’t always on Hollywood’s Mt. Rushmore. This is the man who created those Dan Brown blockbusters, co-starred in a buddy-cop comedy with a slobbering puppy, and has had his share of low professional moments. It hasn’t been all fun and games for Forrest Gump. You don’t work in this field for four decades if you don’t have a Dragnet or two.

Here are the Tom Hanks movies, silly comedies and award-winning dramas, franchise-star turns, and cameos in indies cheer-worthy and cringeworthy.

Sir, thank you for the memories. We’re relieved you’re feeling better.

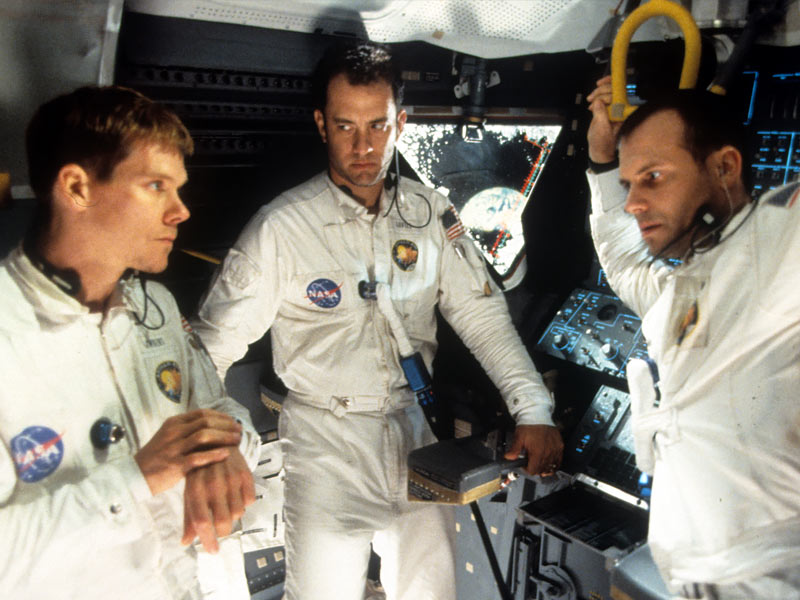

Apollo 13

“We have a problem, Houston.” Ron Howard’s account of the near-disastrous 1970 NASA mission plays out like a disaster film: Three guys are sent into space. Something has gone wrong. This trio of expert pilots works hard to return home safely, with the help of dozens of people on the ground. Anyone with a set of encyclopedias or access to the internet can find out what occurs. What the film does is place you right alongside the astronauts in that floating tin box and get you committed to what occurs, and here is where Hanks comes in – he’s the mission leader in more ways than one.

Jim Lovell is the embodiment of cool and collected under pressure, even when he’s millions of miles away from Earth.

But he’s also the eyes through which we witness the space exploration program’s ambition, successes, and agonies, as well as the ambitions and ambitions of those who would fearlessly venture into the last frontier. It’s not surprising that the star translates all of this through little more than glances and gestures; he does all of this while remembering Lovell is also a mortal who’s like the rest of us, is the balancing act that makes the film work.

Hanks frames the performance as an equation involving intelligence and emotion — you can almost see Lovell thinking in real-time without feeling like you’re seeing a brain in a jar.

And the part allows Hanks to fully embody the attributes we’ve come to identify with him in real life: intrinsic decency, humility, drive, generosity, honesty, and morality. He’s portrayed saintly authority figures, all-American heroes and goofballs, exalted everymen and martyrs, and holy idiots. However, Apollo 13 is likely the only time he’s played someone notable and become memorable in the process.

Sully

Hanks was constantly compared to Jimmy Stewart; now, he gets a shot at being a modern-day Gary Cooper. Clint Eastwood’s account of US Airways Flight 1549’s miraculous landing on the Hudson River — and the pilot, Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, whose knowledge helped avert a major disaster — is part salvage docudrama, part indictment of a system that would call into question the abilities of an honest-to-God American hero. Every time a pencil-pusher invokes “computer simulations” or questions Sully’s professionalism, you can almost feel Eastwood’s rage behind the camera.

However, “doubt” is exactly what this pilot feels, haunted by ideas of what might have occurred; watch the character bristle every time someone refers to him as a “hero.” The performer, in peak silver-fox, stoic-masculinity mode, more than exemplifies Sully’s elegance under duress. But it’s “the human component” that counts in this case, and that’s exactly what the actor brings to the table. If he’s channeling Cooper, it’s the nervous-yet-steadfast Cooper of High Noon, and the battle between those two feelings generates one of the actor’s great late-career performances. Sullenberger was the ideal candidate for the position. Hanks was as well.

Also Read, The Legacy of Keanu Reaves Movies His Bes Works Ever

Sleepless in Seattle

It’s been a year since his wife died, and Sam Baldwin is still in mourning. On Christmas Eve, his concerned, precocious eight-year-old son Jonah dials a national radio show. He asks his father to go on air. Sam, dubbed “Sleepless in Seattle,” receives dozens of offers; nevertheless, it is a letter from a Baltimore Sun reporter called Annie, touched by the broadcast, that draws Jonah’s attention.

Never mind a thousand miles separating them, or her fiancé, or this prospective new lover Dad’s begun courting, or what their respective closest friends say, or the fact that men don’t comprehend An Affair to Remember’s the undying charm. On the Empire State Building’s observation deck, these two have a date with fate. Hanks had already proven his romantic comedy credentials, but this is the film that cemented him as the genre’s sex symbol du jour. He understands how to make Sam sympathetic without being a complete wuss and being lovelorn without being louche.

Philadelphia

“My movie character is very much non-threatening,” Hanks said of his role in Jonathan Demme’s drama in the documentary The Celluloid Closet. “As a result, the thought of a homosexual guy with AIDS is not frightening… [and] a little part of it is that Li’l Tommy Hanks is playing the part.” This studio film about an AIDS-afflicted lawyer suing his firm for wrongful termination was partially intended to put a human face on the pandemic, which meant that the star essentially had to flesh out a persona and become the mainstream’s emblematic martyr for everyone who was living with the disease.

Despite the film’s gravitas, Hanks never comes across as overbearing. There’s a surprising deftness to his scenes of confronting politely delivered prejudices, making peace between his lover Antonio Banderas and the unforgiving world around them, and sparring with Denzel Washington’s homophobic attorney. Even some who felt the film was just a Hollywoodized depiction of the epidemic praised the portrayal. Hanks earned the Academy Award he received for it.

Philadelphia provides enough stage for the actor to rage, most notably an admiration of a Maria Callas aria that the star matches operatic beat for operatic beat.

Captain Philips

This true-life story of a US freighter being hijacked by Somali pirates — and its captain, Richard Philips, being held captive by his captors while they avoid the authorities. It is one nerve-wracking hijacking procedural courtesy of filmmaker Paul Greengrass’s’ you-are-there filming style. But make no mistake: this is Hanks’ film, and despite the shaky-cam sound and fury, the actor never takes a back seat to stylistics. On the contrary, he controls every second he’s up there, outwitting and/or appealing to his kidnappers.

You can see Philips’ mind at work as he realizes what’s going on and continues to outmatch the pirates’ boat; then, once he commences bargaining with his Somali counterpart, you can see him try to conceal the mental chess game he’s playing to save his crew and survive. It’s an incredible push-pull performance, reaching its height in what is perhaps Hanks’ best three minutes onscreen: a pivotal picture of a PTSD breakdown.

Catch me if You Can

Steven Spielberg’s portrayal of a con man, not just any con man, but Frank Abagnale Jr., who successfully floated checks and impersonated an airline pilot, a lawyer, and a doctor, is a legitimate fake-it-til-you-make-it epic and a reaffirmation that this is a filmmaker who enjoys a good feature-length chase. Our “hero” here is Leonardo DiCaprio’s attractive, clever suave criminal. At the same time, Hanks gets to play the square authority figure: FBI agent Carl Hanratty, who will stop at nothing to nab his victim. He’s the Javert to his Leo’s Jean Valjean, the thorn in the forger’s ointment.

But he was also anyone who ended up counterbalancing Frank Srcriminal . ‘s inclinations and acting as a sort of photo-negative father figure to Abagnale, allowing Hanks to take this character to some fascinating places. You can feel Hanratty’s determination in the cat-and-mouse games he plays, as well as his frustration as his guy continues to slip through his fingers. By the end, you can sense pity, reluctant respect, probably even a smidgeon of jealousy, and paternal worry. That’s thanks to Tom Hanks. You like how DiCaprio lets you ride with this expert forger, but you also like how his co-star keeps dragging him back down to Earth. The elderly actor is the real deal in this case.

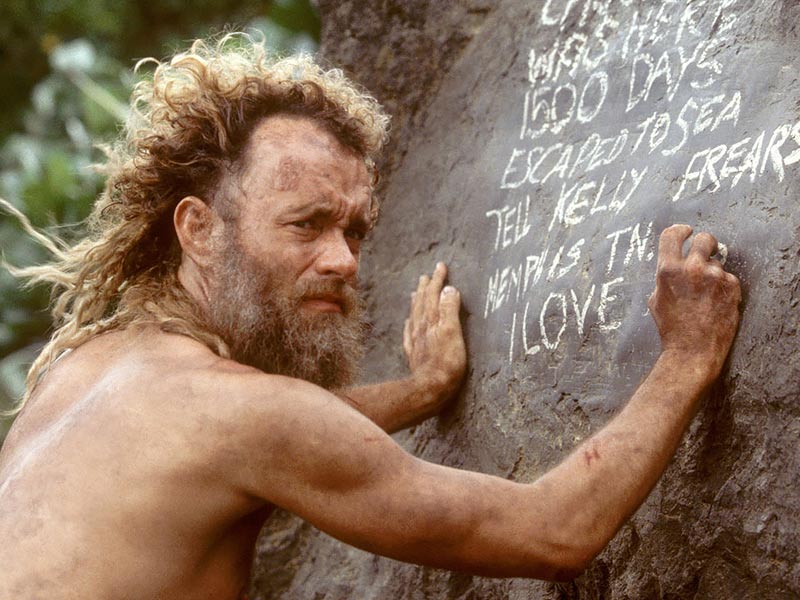

Cast Away

Consider this: how many actors can convincingly form a best friend relationship with a volleyball? For this survivalist story of a Fed-Ex analyst whose jet crashes into the Pacific Ocean, Tom Hanks and Robert Zemeckis reunited. He washes up on the beaches of a barren island and is forced to spend years playing Robinson Crusoe. Hanks, who was never renowned as a Method actor, opted to acquire an extra 40 pounds before filming began; for his last months on the island, production was halted so he could shed around 70 pounds and grow a suitably scraggly, unkempt beard.

What’s more striking than his physical metamorphosis is the way Hanks handles the majority of the drama on his own. He’s the only person onscreen for more than half of the film’s running duration — his only co-star is the Wilson mentioned above, and even those man-meets-sporting-goods segments are painful. Most people remember his major sequences — the dancing around the fire, the reunion with Helen Hunt, the “Keep breathing” speech — but Hanks’ little moments are also memorable. Consider his expression when he is handed a Swiss Army knife after years of producing handcrafted tools. Priceless!

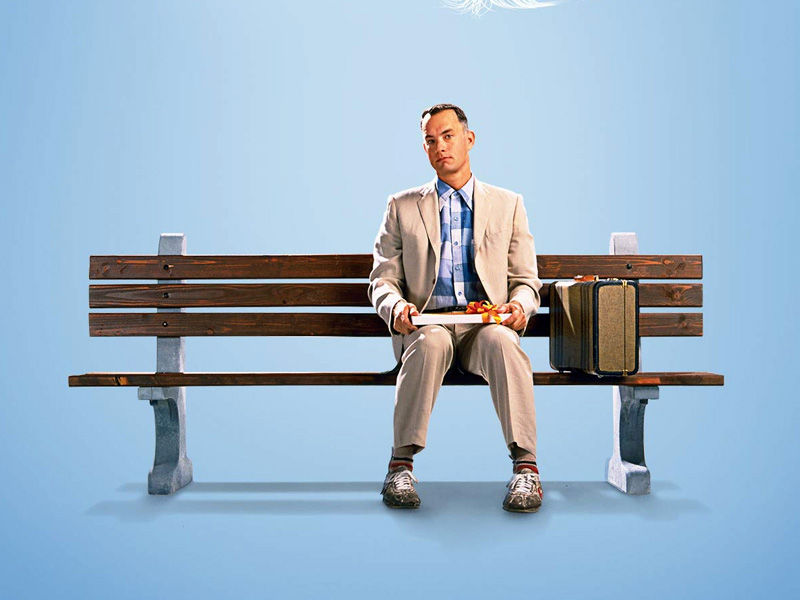

Forrest Gump

It’s not simple to portray a pious fool, let alone one who has to sail across the stormy seas of the twentieth century. From its oversimplified slant on complicated political events to drowning its storyline in heavy-handed sarcasm and cringeworthy aphorisms, Robert Zemeckis’ Oscar-winning, a stupid-is-as-stupid-does riff on Candide has a lot to criticize.

However, Tom Hanks’ interpretation of the title’s American idiot-turned-success tale is not one of them.

This may be one of the finest reaction screen performances ever, with the actor deadpanning, 1000-yard gazing, and/or wide-eyed his way through history – sometimes literally, thanks to a VFX team that inserts Hanks into old newsreel footage from yesteryear. Even though Forrest is a guy who happens to meet presidents, get a “right on” from Abbie Hoffman, and become a ping-pong champion and fitness guru by chance, he manages to make him feel like a fleshed-out figure.

Gump’s inability to understand the world around him does not interfere with his loyalty to friends or his love and affection for Robin Wright’s take-advantage-of-the-new-freedoms martyr; Hanks understands that the no brains, all heart aspect of this hapless hero play like a feature, not a bug, in Eric Roth’s script. It’s up to you whether you think that’s a useful lens through which to examine three decades of American life. Many performers, though, would have been inclined to depict Gump as fumbling and wide. Hanks plays him as a blank slate. He manages to make the tour guide in an otherwise superficial picture appear very profound.

Saving Private Ryan

Everyone rightfully remembers the D-Day scenario that opens Steven Spielberg’s WWII epic, that tour of Normandy’s beaches loaded with war-is-hell shock, awe, and severed limbs. It’s an incredible accomplishment…but so are a lot of show-stopping set-pieces. The rush of pictures the filmmaker throws in just as things are reaching a fever pitch grounds all of that sound and fury: close-ups of Tom Hanks huddled behind a Czech hedgehog and seeing the murder all around him, the sound lowering down to a dismal and monotonous hum. Suddenly, the devastation and destruction on the beach take on a human face, and you can see in his eyes how it has damaged this man’s mind.

Then he’s back in action. Most people would have followed this natural-born leader into battle. Still, Hanks’ captain’s expression provides an edge to all that follows in this hard-shell war film with a sweet, gooey heart. On the other hand, Hanks does not have it; he would obey instructions, but he has witnessed enough bloodshed to be wary of sacrificing more soldiers for a symbolic triumph. The tension between those two poles — patriotic and parental — is palpable in Hanks’ performance. When the film threatens to become too rah-rah cheerful or too dark, you can sense him lifting it up. He makes his performance count for something in the picture.

Also Read, These Movies by Sylvester Stallone needs more Fame

Bridge of Spies

“Everyone is entitled to defend. Everyone is important.” Even if that individual is a well-known Soviet spy living in the United States and might face a death sentence or life in prison. The fourth of Steven Spielberg and five Tom Hanks movies together revisits the time in 1957 when Rudolf Abel was apprehended and prosecuted for treason; Hanks plays James B. Donovan, the lawyer who appeals Abel’s conviction and becomes a social outcast for his pains. He is subsequently summoned to Berlin to negotiate a deal between Abel and a captured American pilot.

It’s a great, flinty performance from Hanks, who understands when to go full Perry Mason in court, when to be serious or somewhat sardonic when addressing his client, and how to read the riot act to a smarmy CIA spook. The director gives Hanks a brief but powerful go-fuck-yourself moment concerning that last element — the “rule book” speech — as well as plenty of opportunities to look pensive and remind you of what the word “patriotic” actually means. Even though the film itself occasionally threatens to become excessively foreboding, Hanks’ portrayal of this legal hawk never does.