The Mughal capital of Delhi never ceases to amaze. In addition to the extensive literature on the subject, one occasionally unearths nuggets of knowledge that are shrouded in mystery.

Would it surprise today’s readers to learn that Shah Jahan (whose birthday was on January 15) not only constructed a new capital but also gave it a special tradition?

Shama Mitra Chenoy claimed that Delhi was both Darul Khalifa and 22 Khawaja-ki-Chaukhat (royal patronage hub and threshold of 22 saints). There were 14 gates: the Delhi Darwaza, the Rajghat Darwaza, the Khizri Darwaza, the Calcutta Darwaza, the Nigambodh Ghat Darwaza, the Kela Ghat Darwaza, the Lal Darwaza, the Kashmiri Darwaza, the Badarroo Darwaza, the Kabuli Darwaza, the Pathar Ghat Darwaza, the Lahauri Darwaza, the Ajmeri Darwaza

In the Walled City, there were 14 Khirkis or windows. According to Prof. Aleem Ashraf Khan, who wrote in the Indo-Persian Society publication Delhi of the Mughals, printed by Mohammed Anees, the city’s four-month-old mud enclosure wall to collapse a year later during a torrential downpour, prompting the emperor to order its reconstruction in stone and lime mortar.

Old Delhi was established in 1639 by Shah Jahan, the Mughal Emperor, who intended to move his capital to a more suitable and spotless position than Agra. His community was experiencing issues with erosiveness, population growth, and drainage, which was prompting the city’s residents to relocate.

Delhi was once known as Shahjahanbad after the city’s founder. The Red Fort, also known as Lal Qila or Qila Mubarak, or Blessed Fortress, was Shahjahanbad’s main tourist attraction. Shah Jahan is thought to have approved the fort in 1638, but the city’s construction didn’t start until 10 years later.

The city of Delhi, which was formed by combining seven historically significant cities and the most recent addition, New Delhi or Lutyen’s Delhi, has a rich history connected to its entrances.

The seventh city to bear Shah Jahan’s name, Shahjahanabad, was established in 1649 and included 16 “khakis,” or wicket gates, along with 14 entry gates. These gates had the names of the cities they led to or illustrious individuals like Shah Turkman. Dilli Darwaza, Kashmiri Darwaza, Turkman Darwaza, Ajmeri Darwaza, and Lahori Darwaza are a few of the gates that are still visible.

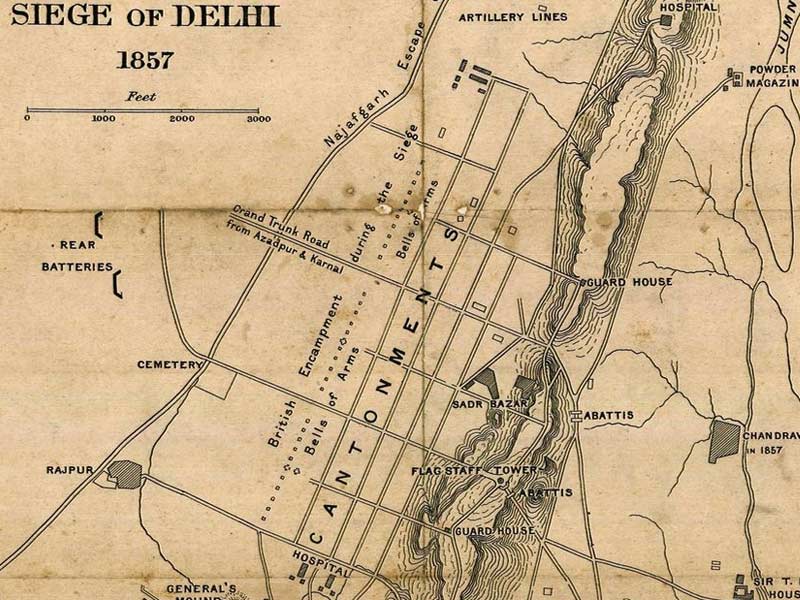

The Kashmiri (Cashmere) Gate is located in the north-western section of Old Delhi, the former walled city of Shahjahanabad. This “Darwaza” has a significant historical context due to the 1857 revolution; rebel sepoys conquered it, locked the gate’s multiple entrances, and fortified its bastion. The Kashmiri Gate was heavily shelled by British artillery from the Northern Ridge. The gate was finally breached in September 1857, four months after the siege. The severely damaged gate is a reminder of the Great Mutiny.

Cemeteries were constructed on the grounds of St. James’ Church, close to Kashmiri Gate, following the Mutiny. St. James Church, which was constructed in 1836, was used frequently by the rebels to meet and plan their course of action. The Mutiny of 1857 caused significant damage to it, and afterward, it underwent extensive restoration. It still stands tall and shining today, telling stories of grief, resiliency, and hope. One of the many birth-death-resurrection phenomena of this extraordinary metropolis is represented by this.

According to the proverb, “Delhi had many gates of admission but none for the exit,” meaning that individuals who came to this city became of the city and the city became theirs to claim, historian R. V. Smith relates this in what may be considered an ode to the old city of Delhi in The Hindu.

Also read: Churches in Delhi: Historical and Cultural Significance

Numerous tales of love, friendship, and treachery, as well as important historical occurrences both spectacular and gruesome, have been told at Delhi’s entrances. I am entering the heart known as Dilli (/) through these identical portals to see it as it is and develops. Many Dillis have been hustling and rustling for a long time, and some still do. Dilli, was the place where no one ever departed and no one was ever left alone. Stories of Dilli, by Dilli, from Dilli—not chronicling, but living.