Sri Lanka economy has a string of Chinese debts under the Rajapaksa family’s rule, including for white elephant projects that have generated little to no revenue

Many Western leaders are behaving as though there is one crisis in the world: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While some are recognizing the widespread implications for food and energy security, it appears that there is little time or resources available to address the underlying crisis: a global economic unwinding triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, climate breakdown, and the degradation of the international political and economic system, which has been in the works for at least a decade.

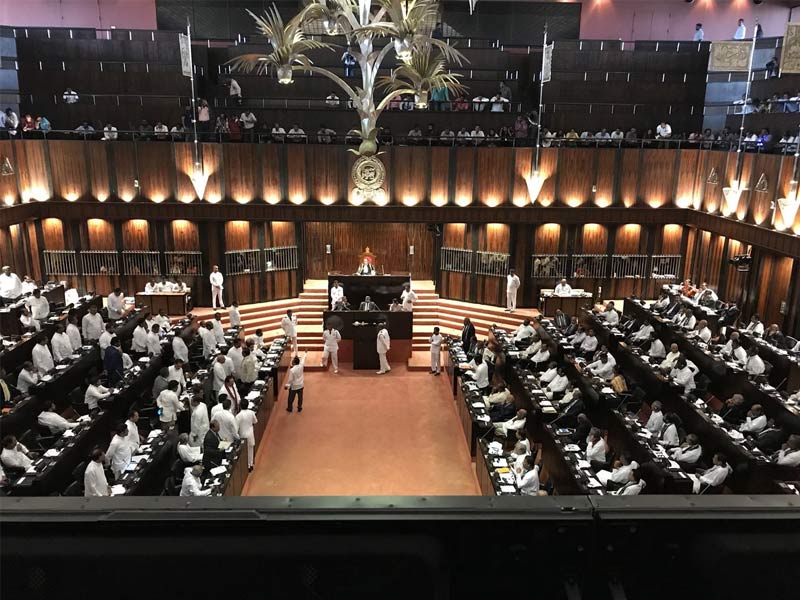

These crises have put a number of countries in grave danger, and they’ve lit a fuse where those dangers collide with authoritarianism and poor governance. Sri Lanka economy is a good example. The country owes over $50 billion to government creditors, including India, China, and Japan, as well as private bondholders, and it has stopped paying interest.

The reasons for the country’s economic woes are numerous. Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s family has ruled the country for much of its recent history, presiding over a populist, security-focused regime that has been chastised for economic mismanagement, corruption, and a brutal campaign to end the civil war in 2009. Several UN reports have criticized its actions during the conflict, citing credible allegations of war crimes and human rights violations.

Sri Lanka economy has a string of Chinese debts under the Rajapaksa family’s rule, including for white elephant projects that have generated little to no revenue—one such project near the Rajapaksas’ hometown was dubbed “The World’s Emptiest International Airport” by Forbes. When COVID-19 hit, they continued to slash taxes despite the fact that tourism had collapsed, wiping out state revenue and personal incomes.

The country has run out of foreign exchange after two years. It was down to its last 24 hours of gasoline stocks last week. Medicine and food supplies are in short supply. Despite ample warnings and mounting protests, the government delayed approaching the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for far too long, and none of the structural and governance reforms necessary for an IMF program to succeed are in place. Instead, the government is still struggling under a caretaker administration with no clear public mandate.

While Sri Lanka’s problems are both self-inflicted and exacerbated by global trends, they are a foreshadowing of what’s to come in a world that can only handle one crisis at a time—and often not even that.

As a result of the Russia-Ukraine war and COVID-19, rising food prices and shortages, as well as security-related supply chain disruptions, large parts of the developing world, are heading for a cost-of-living and sovereign debt crisis, with potentially disastrous consequences.

Sri Lanka and other countries will need debt restructuring in the long run. Creditor countries, particularly the G-20, must improve on the existing “Common Framework,” which has offered middle-income countries like Sri Lanka too little, too late, and nothing at all.

At the very least, any country that enters restructuring should expect an immediate halt in debt repayments, followed by debt reductions tied to a realistic economic growth plan. Private creditors and China must participate, and if they do not, the IMF should step in and lend to the country regardless, on the condition that those who are holding out are not paid.

Such action is contingent on political support from wealthy nations. Too many governments, on the other hand, are turning a blind eye, attempting to ride a wave of patriotism over Ukraine while lacking the vision, will, skill, or bandwidth to respond at scale on this other front, which may be as dangerous to global stability as Russia’s invasion. We must win on both counts in order to win.

Last week, the G-20 finance ministers squandered a chance to make progress on debt. The United States led an important debate on the food crisis at the United Nations, but the discussion devolved into a blame game. The proposed measures are welcome, but those who are still waiting for COVID-19 vaccines, let alone debt relief and climate finance, are likely to be sceptical.

Also read: Sri Lankan Economy and the worst crisis in 73 years

The IMF issued a record $650 billion in Special Drawing Rights in 2021 to boost global liquidity by providing IMF members with a line of credit against which they can borrow. However, pledges by wealthy countries to make such funds available to low-income countries have fallen far short of this goal, with no funds disbursed.

Even Afghanistan, which dominated the news cycle last year, appears to have been forgotten, with the United Nations’ humanitarian appeal only half-funded and shocking reports of people selling children and organs. Countries like Chad and South Sudan, on the other hand, are rarely mentioned on the global agenda.

This is exacerbated by yet another ideologically motivated effort to slash the civil service after the country’s international development ministry was shuttered and the pathetic remnants were folded into the Foreign Office.

Sri Lanka isn’t the only country that needs to make sure that its quest for stability doesn’t exacerbate the failing regimes that have led to its current predicament.

These are enormous challenges: a world of limited resources, weakened government capacity, and mounting domestic issues in the European Union and the United States, such as former US President Donald Trump’s resurgent threat to the Biden administration. The signs aren’t looking good: Last week, the US Congress stymied efforts to reintroduce international COVID-19 funding. At the moment, Washington and its Western counterparts are one-issue towns. They can no longer afford to be so short-sighted as crises multiply.