Mohenjo Daro is located in Pakistan’s Sindh province, in the Larkana District. It is one of the most significant archaeological sites in South Asia, including the UNESCO World Heritage List as an archaeological site of enormous historical importance. It should not be overlooked if you are interested in archaeology or the history of the Indian subcontinent.

A well-planned street grid and an intricate drainage scheme suggest that the inhabitants of the ancient Indus civilization city of Mohenjo Daro were expert urban designers who valued water power. But it’s unclear who occupied the ancient city in modern-day Pakistan during the third millennium BC.

There are no ostentatious palaces, mosques, or statues in the city. There is no visible central government seat or signs of a king or queen. Modesty, discipline, and cleanliness seemed to be favored. Pottery and copper, and stone axes were standardized. Seals and weights imply a closely regulated trading mechanism.

Items such as ivory, lapis, carnelian, and gold rings, as well as the baked-brick city walls, attest to the city’s prosperity and stature.

The Mound of the Dead

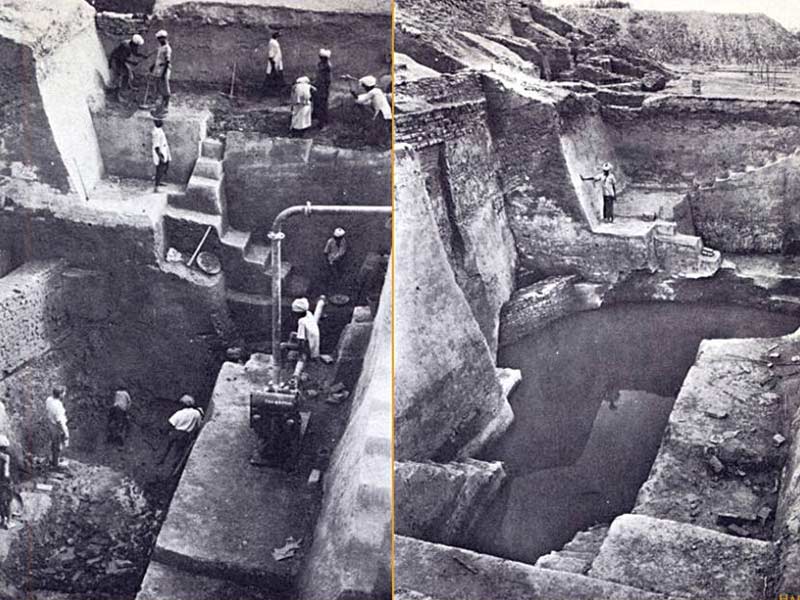

The word Mohenjo Daro is used to mean “the mound of the dead.” The archaeological significance of the site was first recognized in 1922, one year after Harappa was discovered. Subsequent excavations found that the mounds housed the ruins of the Indus civilization’s largest settlement. Because of the city’s size—about 3 miles (5 km) in circumference—and the comparative wealth of its temples and contents, it has historically been known as the capital of a large state. On the other hand, its association with Harappa is unknown—whether the two cities were contemporaneous or whether one succeeded the other.

There is little remaining documentation of architectural elaboration, but it is possible that it was limited to disintegrated timberwork. Stone carving is also scarce; however, some fragments include the capable head and shoulders of a bearded man with a low forehead, narrowed and rather supercilious eyes, a fillet around the brow, and a mantle cut in relief with trefoils formerly packed with red paste over the left shoulder. A renowned bronze of a young dancing child, nude but for a plethora of armlets, is the city’s most notable piece of figurative sculpture.

Also Read, Unknown Facts About Indus Valley Civilization

The most articulate terra-cottas are minimal but robust depictions of bulls and buffalo. Female figurines may wear intricate headdresses, and figurines of short, fat grotesques, male or female, may reveal a coarse sense of humor.

The Great Bath, a watertight pool perched on top of a mound of dirt and kept in place by baked brick walls, is the nearest thing Mohenjo Daro has to a temple.

Wells could be seen all over the city, and virtually every home had a swimming area and drainage system.

The evidence indicates that Mohenjo Daro was subjected to catastrophic floods of unusual depth and length, caused by the encroaching Indus and probably by tectonic uplifts between Mohenjo Daro and the sea. This information has led to theories that Harappa may have succeeded – or at least outlasted – Mohenjo Daro.

Integrity

The Archaeological Ruins of Moenjo Daro consist of 240 ha of burnt brick houses, only about one-third of which has been excavated since 1922. Both of the property’s features are beyond the limits defined for proper maintenance and defense. Many of the important features are now intact and well-maintained. However, the property’s foundations are threatened by salt acts as the Indus River’s water table rises.

Genuineness

The Archaeological Ruins of Moenjo Daro are the remains of the Indus civilization’s first major urban center, built 5000 years ago with burnt brick buildings. The property’s planning, shape, architecture, materials, and place continue to articulate its Outstanding Universal Value. The property’s setting is vulnerable to the effects of nearby construction.

The following are descriptions of some of Mohenjo Daro’s structures:

Stupa (Buddhist temple): The tallest and most visible building in Mohenjo Daro, visible from a long distance. The stupa, written on Pakistani twenty-rupee bills, was constructed atop the citadel mound long after the ancient city had fallen. This later addition to Mohenjo Daro is from the Kushan Empire, dating from the first to fourth centuries CE. In contrast, all of the other excavated ruins date from 2,600-1,900 BCE. It is assumed that the Buddhist Stupa was constructed over the temple, where Hindu deities were revered by the inhabitants.

The Great Hall (Granary): The Great Hall is a massive structure that is thought to have been a granary; it has what seems to be a loading area for carts carrying grain and a ventilation system to avoid spoilage. Another hypothesis is that it was a public hall; its exact use has not been confirmed.

The Assembly Hall (Pillared Hall): This 27.5 m2 brick-pillared building is considered an assembly hall, a spot for people to sit for meetings and social events. Some think it’s a prayer hall or a palace.

The Great Bath: The best-known structure of Mohenjo Daro is a 2.4-m-deep, 12-m-long, and 7-m-wide pool known as “The Great Bath” in the center of a higher settlement. It is constructed of fine baked waterproof mud bricks and a dense coating of bitumen (natural tar – probably to prevent water from seeping into the walls), indicating that it was used for water storage. Many historians believe that this massive deep bath was used for ceremonial bathing or religious rituals. It is the ancient world’s first public water tank. A well next to it was used to provide water to the bath.

College of Priests: A college building is a one-of-a-kind wide open space with a courtyard. This huge house, located to the east of the Great Bath, with several rooms and three verandas, several windows, and two staircases leading to the roof and upper level, is believed to have been the home of a very high official priest or a college for priests.

In the middle of a social media outpouring about how Mohenjo Daro is incorrect, we present a few details about the historical sites of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro. I hope this clarifies something for you:

- Mohenjo Daro was not the historical city’s original name. Nobody knows what the true name is because the Harappan scripture has yet to be deciphered.

- It is also interesting that multi-story structures were discovered at the Harappa and Mohenjo Daro sites.

- There are indications that the Indus Valley Civilisation did not have a monarchy. It was most likely run by an elected council.

- The Indus Valley Civilisation spanned a large area. It ran from Iran to Gujarat and then north to Bactria.

- There are about 1,500 Indus Valley Civilisation sites, although no evidence of warfare or firearms has been discovered. This suggests that the Indus people were benevolent, which may have made them vulnerable to foreign invaders.

- The way of life and religion of the people of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro is still in question. Some artifacts, such as the Pashupati Seal, indicate that the people would worship an ‘animal god’ to shield them from wild beasts.

Years Later, Mohenjo Daro also became a movie.

Ashutosh Gowariker’s epic love tale is set in 2016 BC, and he is an Oscar nominee.

The film centers on a love story set in 2016 BC. A love-struck villager woos a priest’s beautiful daughter as a villainous despot tries to ruin the mighty ancient Indus Valley metropolis.

Sarman, an Indus Valley indigo farmer with a secret royal lineage who moves to the big city to seek his riches, is played by Roshan. It’s true love when he meets Chaani (Pooja Hegde), the daughter of a powerful priest. However, the two are confronted by a power-hungry city chief, Maham (Kabir Bedi), and his ruthless son and successor (Arunoday Singh). All of them are challenged by the revolution that Sarman represents. The arrogant Maham’s massive dam proves to be his grandiose undoing, but Sarman saves the day.