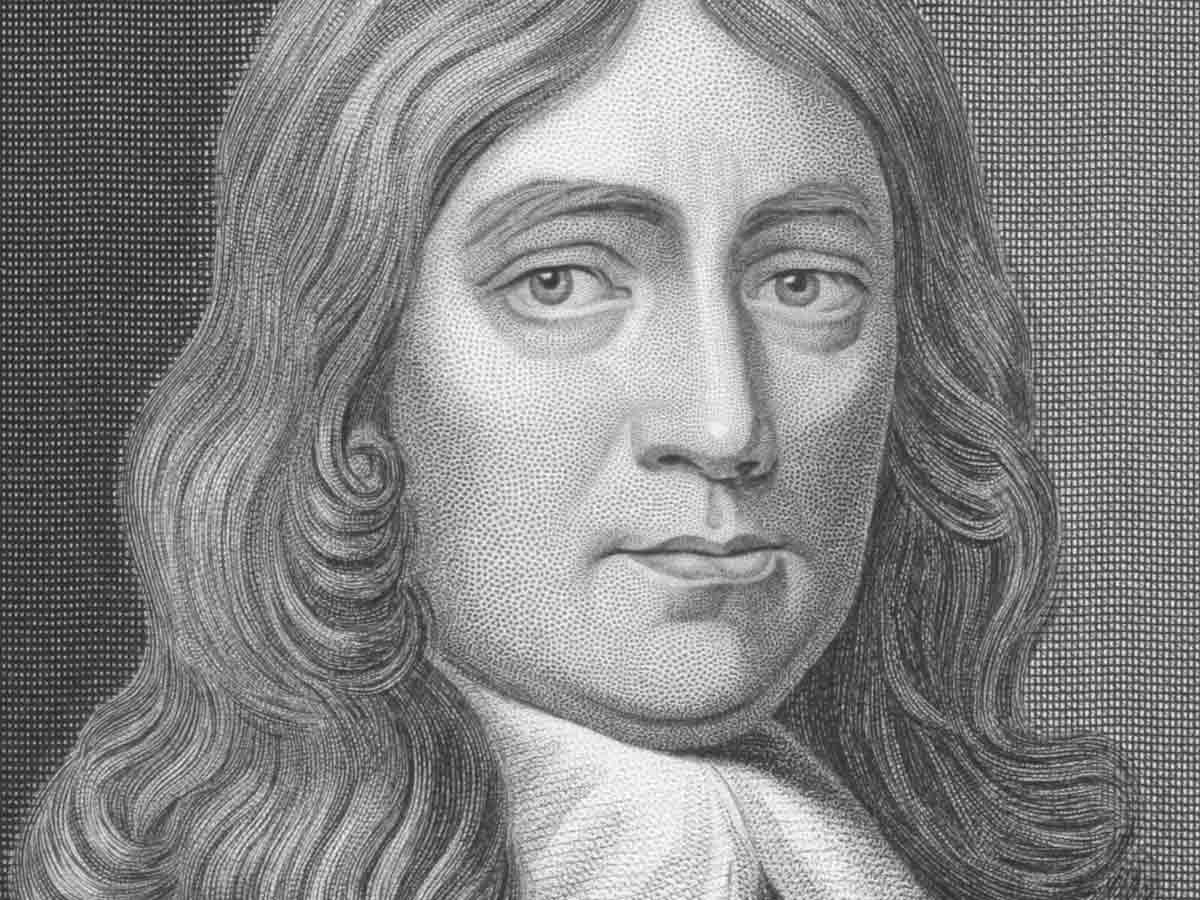

John Milton (1608-74) is one of seventeenth-century most prominent poets – indeed, one of English literature’s most significant and influential poets. Paradise Lost, he is rightly praised for composing the definitive English epic in his long narrative poem, but John has published several more.

So, a top 10 Milton, huh? This is the more difficult since John Milton’s most famous works are very lengthy. He did not publish his poetry extensively outside of these main works. We could delve into his day in his schoolboys, or we could find plenty of macaronic verses in many languages at a time. We could be better Latin than we would have liked, but we will stick to English. We selected a few extracts from his works, but Paradise Lost and Samson Agonists are both one of the top ten poems. As a consequence, here we earn a lot of jobs.

We are happy to say there might be a lot of discussion around the six bottom points. Still, we think the only argument about which order is in the top four. Not a few people will put the number one “Methought I saw my late-wedding Saints,” and maybe even those who read both of them would rate Paradise Lost above Samson’s Agonists. However, as we read them, we are defending our ranking.

We bring you the best of John Milton. The 10 best pieces of John Milton.

Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost (1667) was probably the greatest epic poem in English, not Milton’s first epic attempt. John Milton started as a youth to compose the Gunpowder Plot in the Latin language; however, he remained in quantum November. Instead, his defining work will be his 12-book poetry on Man’s fall, his Pandemonium creation (the capital of the Hell). Consequently, Eve’s trial in the Garden of Eden was stripped from Satan’s heavens.

“Of Mans First Disobedience, and the Fruit

Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal tast

Brought Death into the World, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, till one greater Man

Restore us, and regain the blissful Seat,

Sing Heav’nly Muse, that on the secret top

Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire

That Shepherd, who first taught the chosen Seed,

In the Beginning how the Heav’ns and Earth

Rose out of Chaos…”

Lycidas

When John Milton was drowned as Milton’s friend, young aspiring poet Edward King, in 1637 when his ship sank on the Irish Sea off the coast of Wales. John Milton made the poet, his Cambridge university friend, a pastoral individual of King’s ideal, his official elegy. Many novels have drafted names from John Milton’s poetry, including The Sheep Look Up by Thomas Wolfe, Angel, and John Brunner.

Yet once more, O ye laurels, and once more

Ye myrtles brown, with ivy never sere,

I come to pluck your berries harsh and crude,

And with forc’d fingers rude

Shatter your leaves before the mellowing year.

Bitter constraint and sad occasion dear

Compels me to disturb your season due…

L’Allergro

The two subsequent novels, this and the next, are a conflicting pair: ‘L’Allegro’ means the ‘happy man’ and sees John Milton as ‘Lycidas’ beyond playing with pastoral poetry. However, it’s a lovely and up-to-date poem that adds joy and joy to an elegy note. This also contrasts strongly with ‘L’Allegro’…

“Hence loathed Melancholy,

Of Cerberus, and blackest Midnight born,

In Stygian cave forlorn,

‘Mongst horrid shapes, and shrieks, and sights unholy;

Find out some uncouth cell,

Where brooding Darkness spreads his jealous wings,

And the night-raven sings;

There under ebon shades, and low-brow’d rocks,

As ragged as thy locks,

In dark Cimmerian desert ever dwell…”

Il Penseroso

The ‘L’Allergro’ (‘the happy man’) is very distinct. The Penseroso is a reflexive ode that sees pleasure as an illusion (‘the melancholy man’: from the notion that thought makes you so sad): “Hence vain deluding Joys,

The brood of folly without father bred,

How little you bested,

Or fill the fixed mind with all your toyes;

Dwell in som idle brain

And fancies fond with gaudy shapes possess,

As thick and numberless

As the gay motes that people the Sun Beams,

Or likest hovering dreams

The fickle Pensioners of Morpheus train.”

When I Consider How My Light Is Spent

This sonnet was sometimes referred to as ‘On His Blindness’ in the early 1650s as a loss of John Milton’s sight. Worried about how he will represent God better as he loses his view, Milton recommends being careful, ending with a line and feeling that have since been known beyond the poem:

‘God doth not need

Either man’s work or his own gifts; who best

Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. His state

Is Kingly. Thousands at his bidding speed

And post o’er Land and Ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.’

Also Read, Some of the greatest poets the world ever witnessed

On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity

This ode is about – well, the title almost says it all. It was in December 1629 when John Milton was only in his early twenties. This is a poem about the coming of Christmas on Christmas Day. To read the complete poem, click on the link above, but here are the stances:

This is the month, and this the happy morn,

Wherein the Son of Heav’n’s eternal King,

Of wedded Maid, and Virgin Mother born,

Our great redemption from above did bring…

Methought I Saw My Late Espoused Saint

One of the best poetry about a wife’s loss, even though not everybody is a fan (Samuel Johnson was famously sniffy over this sonnet). The subject was believed to be Katherine Woodcock, John Milton’s second wife, who died in 1658 after her daughter was born (who also sadly died).

Methought I saw my late espoused saint

Brought to me, like Alcestis, from the grave,

Whom Jove’s great son to her glad husband gave,

Rescu’d from death by force, though pale and faint…

On the Late Massacre in Piedmont

The Duke of Savoy destroyed the Waldensians (an ascetic Christian sect) in Piedmont in April 1655, with troops commanded by Charles Emmanuel II. In this horrible incident, John Milton wrote the following sonnet. The relation of Milton to the ‘triple dictator’ is a reference to the Pape.

Avenge, O Lord, thy slaughtered saints, whose bones

Lie scattered on the Alpine mountains cold,

Even them who kept thy truth so pure of old,

When all our fathers worshiped stocks and stones…

How Soon Hath Time

A (slightly) lighter poem now, but one shot with an awareness of death and distance. At the age of 23 (or maybe 24, the proof is sketchy), John Milton wrote the sonnet, but he already felt old. He was still calling Cambridge University, but now his contemporaries were left behind as he embarked on this long journey to prepare for a great life.

The poem reveals just how precocious the young John Milton was, and, while not his main success in his best-known poem, he wins place on this list for showing Milton’s potential.

How soon hath Time, the subtle thief of youth,

Stol’n on his wing my three-and-twentieth year!

My hasting days fly on with full career,

But my late spring no bud or blossom shew’th…

On Shakespeare

Another early poet here in 1630 and one of John Milton wrote ‘How soon Hath Time’ – when he was much younger than he was! When this poet looks like Milton is praising a former poet, this picture of Milton’s best poetry seems to be a suitable poem, especially because Milton’s notes about Shakespeare’s work have just come out.

What needs my Shakespeare for his honoured bones,

The labor of an age in pilèd stones,

Or that his hallowed relics should be hid

Under a star-pointing pyramid?

Dear son of Memory, great heir of fame,

What need’st thou such weak witness of thy name?

Thou in our wonder and astonishment

Hast built thyself a live-long monument…

About John Milton

John Milton was a late Renaissance English poet (Born December 9, 1608 – died November 8, 1674). His poetry about Satan and Adam and Eve’s fall out of the Garden of Eden, Paradise Lost, which he wrote when he became blind, is most noteworthy. He studied Latin, Greek, and Italian at the University of Cambridge. His Puritan religion and opposition to the English Church contributed to his inclusion in the British Civil War. Milton had a strong status, effectively making him a leading propagandist after the ascent of the Puritan General and Parliamentary Oliver Cromwell over the British Commonwealth.