Kanishka I, also known as Kanishka the Great, was a Kushan monarch whose reign (c. 127-150 CE) saw the empire reach its pinnacle. His military, political, and spiritual achievements have made him famous.

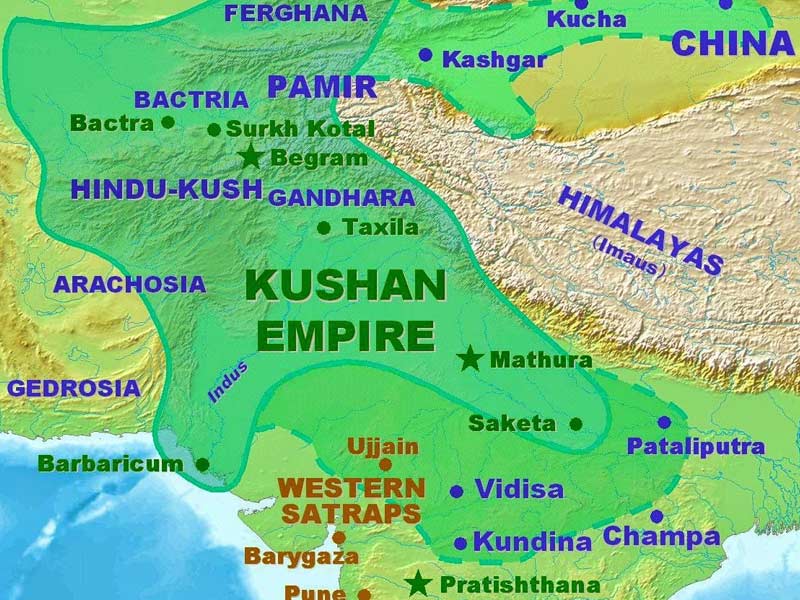

Kanishka, a descendant of Kujula Kadphises, the Kushan empire’s founder, ruled over an empire that stretched from Central Asia and Gandhara to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain. His empire’s principal capital was in Gandhara, at Puruapura (Peshawar), with another significant capital in Mathura. Kanishka coins were discovered in Tripuri (present-day Jabalpur).

His conquests and support of Buddhism were crucial to the Silk Road’s development and the transmission of Mahayana Buddhism from Gandhara to China over the Karakoram mountain. Around 127 CE, he substituted Greek with Bactrian as the imperial administration’s official language.

Previously, scholars thought Kanishka ascended the Kushan throne in 78 CE, and that this date was chosen to start the Saka calendar period. However, historians no longer consider this to be Kanishka’s accession date. According to Falk, Kanishka ascended to the throne in 127 CE.

Kanishka was of Yuezhi origin and a Kushan. Tocharian A was most likely his native tongue. The Rabatak inscription uses a Greek script to write a language known as Arya (), which was most likely a variety of Bactrian endemic to Ariana during the Middle Iranian period and was an Eastern Iranian language. The Kushans, on the other hand, most likely adopted this to make communication with local subjects easier. What language the Kushan elite spoke among themselves is unknown.

Kanishka was the son of Vima Kadphises, according to the Rabatak inscription, which has an outstanding genealogy of Kushan kings. The Rabatak inscription describes Kanishka’s relationship with earlier Kushan monarchs, as Kanishka makes a list of the kings that ruled before him: “For King Kujula Kadphises (his) great grandfather, and for King Vima Taktu (his) grandfather, and for King Vima Kadphises (his) father, and for himself, King Kanishka,” says the inscription.

Kanishka ruled over a massive empire. It stretched from southern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, north of the Amu Darya (Oxus) in the north west, to northern India, as far as Mathura in the south east (the Rabatak inscription even claims he held Pataliputra and Sri Champa), and it included Kashmir, where there was a town named after him, Kanishkapur (modern-day Kanispora), not far from the Baramula Pass, that still contains the base of a large

The extent of his control over Central Asia is less well known. General Ban Chao conducted fights near Khotan with a Kushan army of 70,000 soldiers led by an otherwise unknown Kushan viceroy called Xie in 90 AD, according to the Book of the Later Han, Hou Hanshu.

Ban Chao declared victory, claiming that he used a scorched-earth policy to force the Kushans to flee. In the Tarim Basin, modern Xinjiang, the Chinese dependencies of Kashgar, Khotan, and Yarkand existed. Several Kanishka coins have been discovered in the Tarim Basin.

One of Kanishka’s main imperial ambitions appears to have been to control both land (the Silk Road) and sea commerce routes between South Asia and Rome.

Also read: Mauryan Empire: The Great Empire of Ancient India

Coins

Kanishka’s coinage feature representations of gods from India, Greece, Iran, and possibly Sumero-Elam, illustrating his theological syncretism. Kanishka’s coins, which date from the beginning of his reign, have Greek legends and represent Greek divinities. Later coins have tales in Bactrian, the Iranian language spoken by the Kushans, and Greek deities have been supplanted with Iranian deities. Kanishka’s coins, even those with a Bactrian legend, were all written in a modified Greek script with one additional glyph, as in the words ‘Kushan’ and ‘Kanishka.’

The monarch is usually shown as a bearded guy wearing a long coat and gathered-at-the-ankle trousers, with flames issuing from his shoulders, on his coins. He is dressed in enormous rounded boots and wields a long sword and a lance. He’s frequently seen sacrificing something on a little altar. The bottom half of a lifesize limestone relief of Kanishka dressed identically, with a stiff embroidered surplice beneath his coat and spurs fastened to his boots under the light gathered folds of his trousers, remained in the Kabul Museum until it was destroyed by the Taliban.

Kanishka and Buddhism

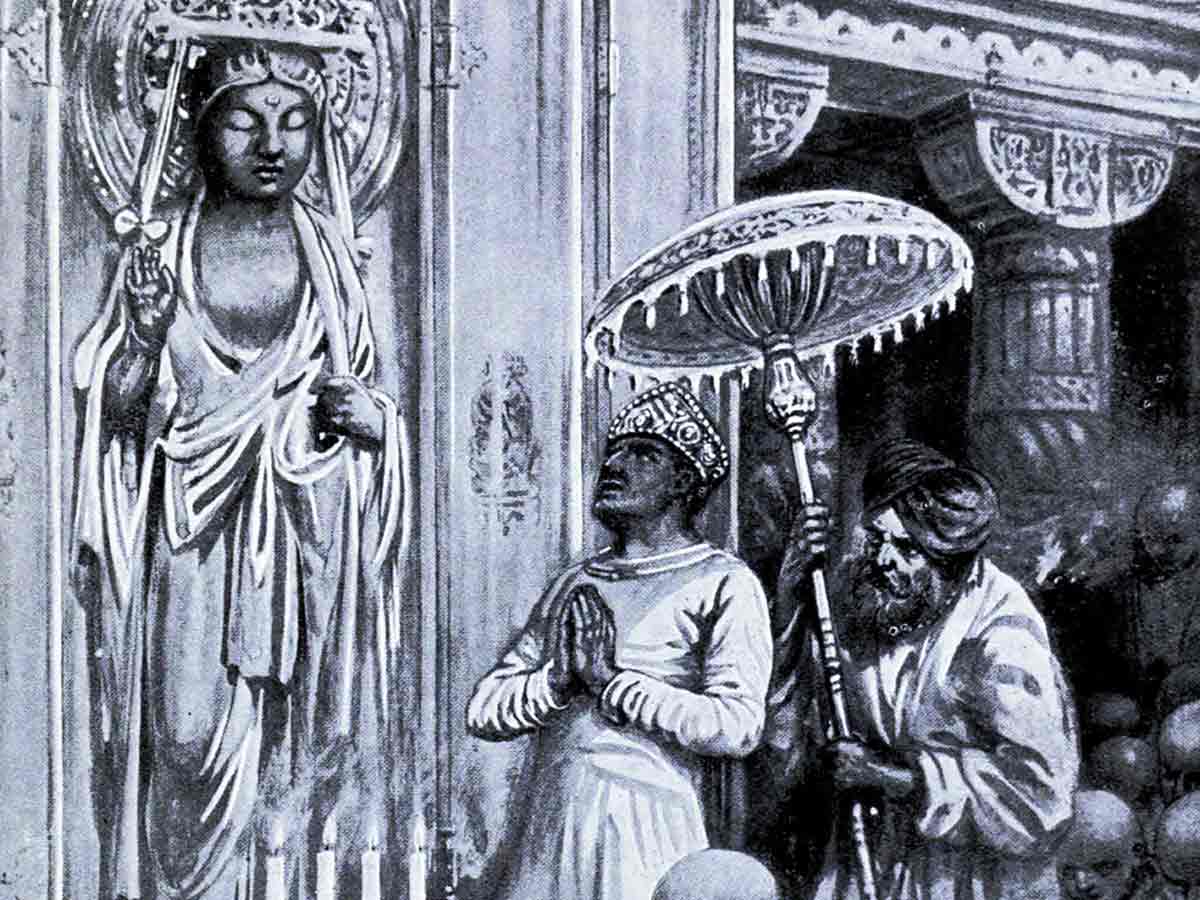

Kanishka’s Buddhist reputation was highly valued since he not only believed in Buddhism but also actively promoted its teachings. He demonstrated this by serving as the head of the 4th Buddhist Council in Kashmir. Vasumitra and Ashwaghosha presided over it. During his lifetime, 32 physical signals were used to create Buddha images.

He promoted the Gandhara School of Greco-Buddhist Art as well as the Mathura School of Art (an inescapable religious syncretism pervades Kushana rule). Kanishka appears to have accepted both Buddhism and Persian traits, but his preference for Buddhism may be shown in his adherence to Buddhist teachings and prayer techniques depicted in numerous kushan empire literature.

Buddhism to China

From the middle of the second century CE, Buddhist monks from the Gandhara region played a crucial role in the development and transmission of Buddhist concepts to northern Asia. Lokaksema (c. 178 CE), a Kushan monk, was the first to translate Mahayana Buddhist scriptures into Chinese and established a translation bureau in Loyang, China’s capital.

Buddhist monks from Central Asia and East Asia appear to have kept strong ties for millennia.

Huvishka was most likely Kanishka’s successor. It’s still unclear how and when this happened. In the entire Kushan legacy, there was just one king named Kanishka. Kanishka’s signs can also be seen in the inscription on Hunza’s Sacred Rock.