At the age of only twenty-five, John Keats (1795-1821) died but left a considerable amount of work behind, as he died so young. However, some of his poems instantly seem to be one of the “best” of his career.

This list aims to collect poems that represent John Keats’ exceptional genius and ability to deal with a variety of subjects and forms, rather than his most famous. Since we’ve wanted to concentrate here on his short poetry, three of his longer narrative poems must be honored: “Isabella,” “The Eve of St Agnes,” and “Lamia.” There were even more great poems, so here’s our choice of John Keats’s ten best poems.

We have listed out 7 of the best poems by John Keats.

Ode to Psyche

‘Ode to Psyche’ is the oldest John Keats’ Odes in 1819 about the Greek incarnation of the Psyche, the spirit and mind. Keats announces that he will be the ‘priest’ of Psyche and construct a temple for her in his mind. While this may be the least appreciated in John Keats’ classic odes, it is a fine paean to literary ingenuity and force of imagination – while the ‘odes on indolence’ is rival to them.

“Yes, I will be thy priest and build a fane

In some untrodden region of my mind,

Where branched thoughts, new grown with pleasant pain,

Instead of pines shall murmur in the wind” …

Ode to Melancholy

This time we approach the readers personally and tell us the right way to deal with a blues situation. Another one of the popular odes. He said that we should encourage ourselves to wallow in sadness by sitting on the transience of all – including melancholy itself, instead of attempting to shaking it off or ignore it. It’s remarkably like an order to ‘live every day as you were,’ to avoid moping (though to be acknowledged, John Keats’s way of doing this is considerably more poetic); it’s like the injunction to ‘live every day as your last one.’ When we’re satisfied, we stop appreciating pleasure, so we consider it to be obvious.

Encompassed by brilliantly vivid images, this poem only succeeds in describing Death by embracing the many masterpieces of life and the natural environment. It is not always easy to say as a piece of contradiction, whether constructive, cynical or even a combination of both. Anyway, Keats is one of its best poems by careful development and a pure volume of pictures.

“But when the melancholy fit shall fall

Sudden from heaven like a weeping cloud,

That fosters the droop-headed flowers all,

And hides the green hill in an April shroud;

Then glut thy sorrow on a morning rose,

Or on the rainbow of the salt sand-wave,

Or on the wealth of globed peonies …”

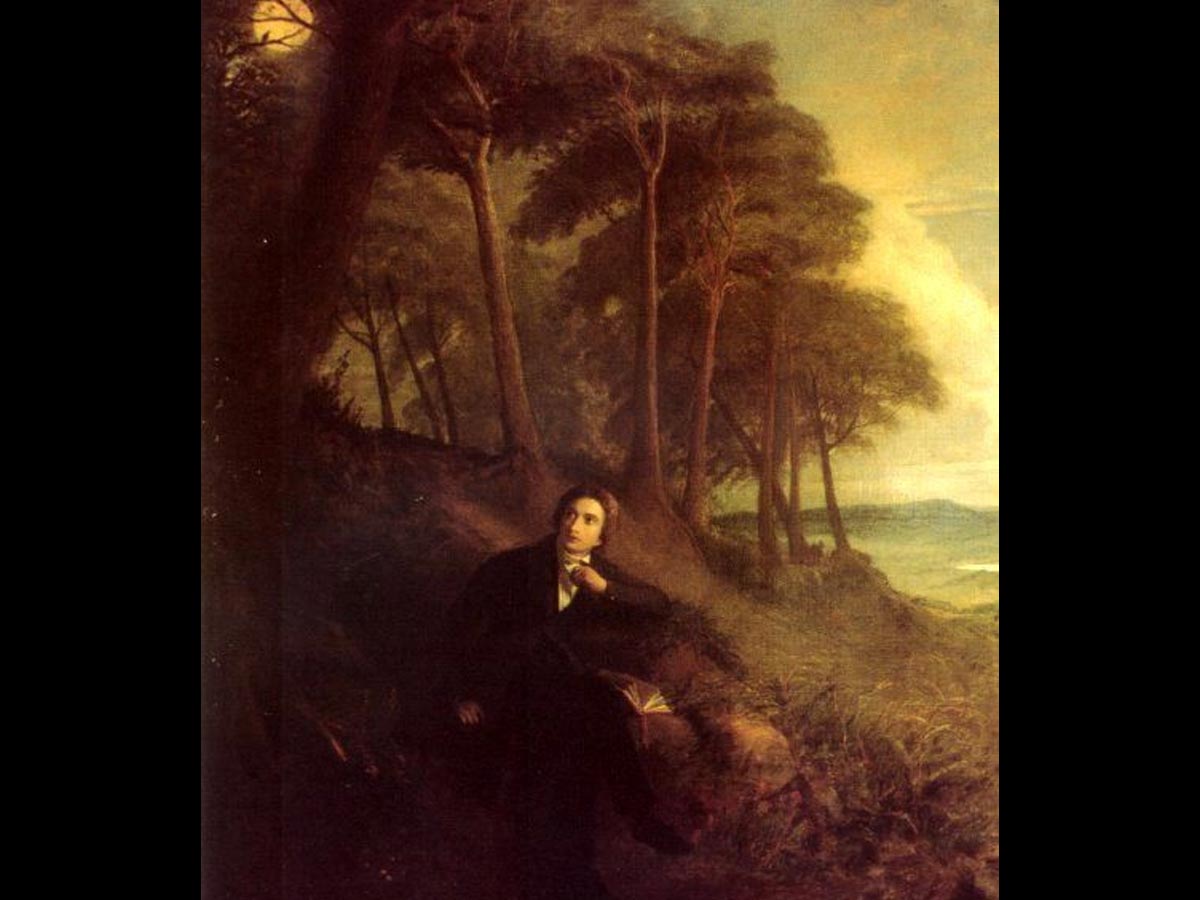

To Autumn

One of the most famous of all time, the first paragraph of this poem. No other poet could have so delicately or so kaleidoscopically crafted such a stunning reflection of the season. With just three stanzas, John Keats can express three months of synesthesia. In places, the naturalistic, almost pastoral vocabulary recalls Hardy, but it does too much with a fraction of the words.

Keats ‘To Autumn is also one of the best autumn poems in the language, perhaps the most popular poem of this season in English literature. In his eco-criticism book, Jonathan Bate has a fine assessment of the poem.

‘The fine air is how lovely this season is—a deliberate narrowness. Really, I have never enjoyed stubble-fields so much, without kidding, chaste weather—skies—I Dian’s like it greater than the chilly green of Spring. Somehow, a stubble field looks warm — much as some photos look warm. It hit me too hard on the way to my Sunday that I wrote about her.” John Keats then wrote in a letter of September1819 that drew attention to the source of ‘To Autumn in Winchester, Hampshire, and the circumstances in which he composed the work.

“Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core …”

La Belle Dame sans Merci

One of John Keats’ most popular poems is perhaps sad to have such a humble spot (though it would never be easy for so many of them to choose); after all, “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” is a legendary poet, picked from Arthurian legend and immortalized in the sparse melodic verse of Keats. Desolate arrangements and dreary rhyme schemes express the artistic merit of the poem. Still, the balance of force between man and woman, as with other works such as “Lamia” and “The Eve Of St Agnes,” is also a central theme. The first few verses of the narrative poem are in this article.

It tells the story of a knight in arms, who was seduced by a wife who was fairer than a man (You know the kind), who loaded back into her cave and then left him on the freezing hillside. This ballad was one of John Keats’ most famous poems. The knight and the lady have a sense of reciprocity, but now even they remain open to doubt.

While we may see the knight simply as a passive observer, used by a lovely heroine (another victim who fades under the spell of the lovely woman without mercy), it should also be noted that the action in this ballad has a to-and-fro nature: the knight offers the lady three gifts, and she answers with three gifts. He silences her kissing sighs before silence him in his sleep by singing him a lullaby.

“I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She looked at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song …”

Also Read, The Best of works of John Milton

Ode to Nightingale

This poem again provides us with an insight into his conception of imagination and composition in another ode written in John Keats’ annus mirabilis of 1819. The enchantment and potioning advice arrive with abstract ingredients such as ‘a beaker full of warm South.’ The nightingale is unattainable, both as a creature and as an emblem, leading to a vivid Keatsian flight. The first few stanzas are here.

In contrast to the ‘Ode on a Grecian urn,’ contemporary critics and reviewers of Keats’ work have praised this fellow ode. John Keats was published in House’s garden in London in May of 1819 under a plum tree. The birdsong’s tone influenced Keats, and this poem is written to the love of the nocturnal. It is a clever poet about mortality and the attraction of Death and flight, like the ‘Bright Star.’ The expression’ tender is the night was taken from this poem by F. Scott Fitzgerald as the title of his 1934 book.

“Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain,

While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad

In such an ecstasy!”

Ode to Grecian Urn

This is probably his most metaphysical of the many great odes that John Keats published in 1819. It deals with the relationship between art and humanity (as shown by the urn creation) and how important true beauty is for human beings. This poem leaves us with an emotion of hope, as opposed to the more despondent “Odes on Melancholy” or “Ode to a Nightingale,”: the urn figures are at an ever-growing joy, “Songs forever new,” that never get raved by time. As Keatsian as it becomes, the Romantic idea is:

This is one of John Keats’ finest odes, inspired by the scenes seen in an ancient Greek urn. Initial readers, however, did not think so: it met a timid reception in 1820. Since then, however, its status as one of Keats’s most polished poems has been founded – including the popular final two lines, ‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty – that is all / Ye know on earth and all ye need to know.’

“What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter …”

There are also hundreds of stunning works from John Keats down to the top Seven. There you have them! Certain much-loved poems have been skipped, so please comment down below (or maybe believe some reorganization is in order) if you want justice to a certain poem.

About John Keats

He becomes the son of the stable owner. He ends his life as an unmarried, sick, and tuberculosis-ridden young man, John Keats (born October 31, 1795 – died February 23, 1821). He happened to become somewhere along the way one of the most loved English literary authors, a fine example of romance.

To read all of his poems click here.