Min Jin Lee’s best-selling novel on the tough life of Koreans in Japan has been adapted for Apple TV+ as a glamorous family story.

Millions of Japanese people are addicted to the pinball-style arcade game pachinko. Millions more people worldwide may soon become addicted to “Pachinko,” a soapy, melancholy television series. The makers of “Pachinko” have masterfully tuned the mechanism of their plot to generate a guaranteed crowd-pleaser, much as pachinko-parlor owners delicately manipulate their machines’ pins and cups to keep gamblers in their seats.

The series is based on the 2017 bestseller by Min Jin Lee in three of its eight episodes – sometimes faithfully, more often with a weak link, if any, to the book’s events, concepts, and tone.

Lee’s work, which began with the foreboding sentence “History has failed us, but no matter,” depicted the terrible existence of four generations of a Korean family living in a violently racist Japan, confined to poverty and unable to return home due to discriminatory legislation and international politics. If not their position, their fortunes begin to shift when one of them becomes a pachinko guy. This industry is only open to ethnic Koreans due to its negative associations.

Lee used what may be viewed as truths or handy stereotypes about Koreans — tenacity, passion, hard effort, astute business instincts — in the service of a huge melodrama. The book “Pachinko” is a page-turner. Still, its attention to character and period aspects (it spans eight decades, beginning in 1910) and its constant, unforced narrative thrust give it considerable strength. It has the sense of a nineteenth-century novel, similar to the Victorian works enjoyed by one of its protagonists, the intellectual Noa.

In contrast, “Pachinko,” the TV show, has a modern sensibility, and it strives tirelessly to ingratiate itself with all potential viewers.

That ambition is clear in the opening credits scene, which is set to a pop song, the Grass Roots hit “Let’s Live for Today”: the key cast members, dressed in period costumes but acting out of character, dance amid the pachinko machines, sliding and spinning and posing for the camera. It’s difficult to imagine something more dissonant with Lee’s book.

Of all, the show’s creators — Soo Hugh (“The Whispers,” “The Terror”), who conceived and was the principal writer, and directors Kogonada and Justin Chon — had no responsibility for the book, and their “Pachinko” has its enormous pleasures. The credits sequence is pure visual candy, with its brilliant but washed-out palette. The show looks terrific overall, particularly in the early episodes directed by Kogonada and photographed by Florian Hoffmeister.

The extensive reconstructions of early twentieth-century Korean markets and fishing towns and the Korean ghetto in prewar Osaka, built in South Korea and British Columbia, are luxuriously gorgeous and credibly lived-in. ” Pachinko ” period elements are unrivaled in a visually appealing costume drama.

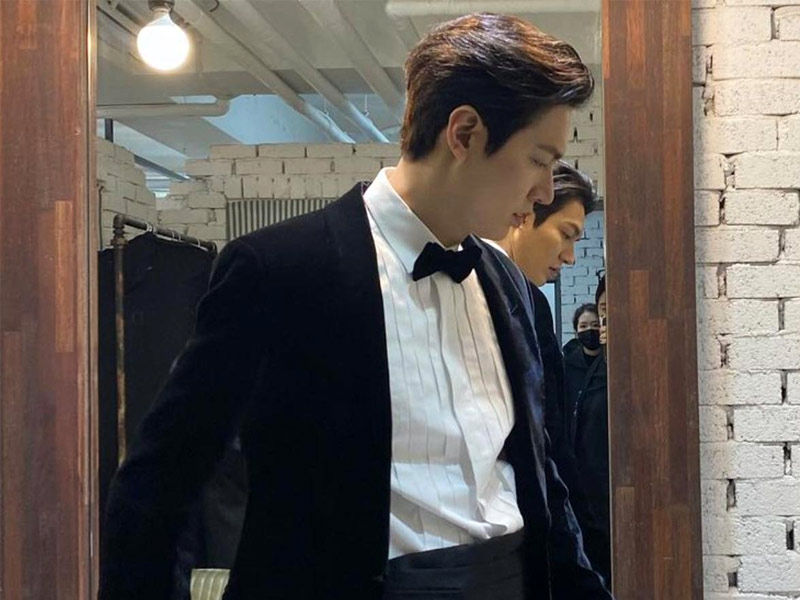

It’s also difficult to argue with the show’s huge, largely South Korean and Japanese cast. (The speech is mostly Korean and Japanese, with subtitles in different colors.) The indomitable Sunja is performed with equal grace by the Oscar-winning Yuh-Jung Youn (“Minari”) as a long-suffering matriarch and debutant Minha Kim as a young wife and mother. Another notable South Korean star, Lee Minho of the popular K-drama “Boys Over Flowers,” plays Hansu, Sunja’s lover and her Magwitch-like patron.

Also Read, Deadly Class: (Caution) A Hard to Watch Syfy Series

These actors achieve something powerful here and there — usually in the scenes taken most closely from the novel — such as the painful scene between Sunja and her mother, Yangjin (Inji Jeong), after Sunja leaves Korea. Too often, though, their work is coated in several layers of Hollywood gauze, and the sensitivity of their performances is disguised by the production’s general tendency toward stylish schmaltz.

This is clear at times, as seen by the cooing vocalization and ad-agency camerawork when Yangjin makes a special goodbye supper of hard-to-find white rice. However, it is identifiable mostly as an overarching sensibility and in changes that make the characters more conventionally accessible and the events more traditionally dramatic than they were on the page.

As a result, Sunja (Yu-na Jeon) has grown into a lovely, precocious moppet, and Annie of the fish market, and her father, Hoonie (Dae Ho Lee), has transformed from stoic and noble to brilliantly philosophical. A series of plot developments, such as how Sunja and Hansu begin spending time together and how the compassionate pastor Isak (Steve Sanghyun Noh) broaches the subject of marriage with Sunja, appear to be intended to reassure existing viewers who desire a female protagonist with greater agency. However, they don’t add anything to the plot. His original point was how little control Sunja had over the direction of her life.

(In another tribute to shifting sensibilities in the five years since the book’s release, one of the main bad characters, who was Japanese in the original, is now white.)

Viewers who have already read the book may be distracted by several structural alterations. The tale now runs on many time tracks, alternating between past and present. Major chunks of the story have been added, such as an entire episode set mostly during the Kanto earthquake of 1923, which resulted in a massacre of Koreans. Other key plot strands from the book are absent entirely.

The entrance of a dazzling, ill-fated entertainer on the ocean voyage to Japan has strong overtones of “Titanic.” They strive hard to make the program a conventional, romantic, and inspiring narrative. They are also useful because, while “Pachinko” is based on a self-contained novel, it is not a mini-series. New material is required, and material from the book should be saved for possible future seasons.

“Pachinko’s” release follows the exceptional success in America of South Korean films and TV dramas such as “Parasite” and “Squid Game,” and it has the soap-operatic appeal of a well-made K-drama. However, as an adaptation of a popular novel by an Asian-American author brought to the screen by an Asian-American artist with an ethnically Asian ensemble, the more apt parallel is to Wayne Wang’s “Joy Luck Club” from three decades earlier.

When it comes to “Joy Luck Club” and “Pachinko,” Hollywoodization is the operative term, whether voluntary or not. And, to the extent that glossy melodrama draws spectators into a story that introduces them to new characters and treats the hostility and injustice they encounter with honesty, it’s not a negative term.

But behind its luster and likeability, “Pachinko” is very average – a lot of effort has gone into producing something pleasantly consumable.