My name is Woo Young-woo, whether you read it correctly or incorrectly. Racecar, noon, deed, kayak, and Woo Young-woo. Yeoksam Station (the Korean word for the station is yeok). To explain herself, our main protagonist identifies other palindromes that sound like her name.

For Young-woo (Park Eun-bin), a 27-year-old rookie attorney with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), the first impression is vital to understanding who they are as a person because, as she puts it, “I’m not an ordinary attorney.”

At the tender age of five, the day she received her initial diagnosis of ASD, she developed a passion for the law. Woo Gwang-ho (Jeon Bae-su), who was at the time pursuing a law degree at Seoul National University, was her sole parent when she was growing up.

Young-woo had read and memorized each and every line in her father’s law textbooks, unbeknownst to him until he had gotten into a physical altercation with his landlord over a misunderstanding, even though she was unable to communicate on a level that was comparable to the rest of her peers.

Young-woo started reciting the criminal statutes against inflicting bodily harm on others, along with the legal consequences if the attacker were ever found guilty of such an offense, as she became more and more agitated and terrified. Gwang-ho was completely speechless as he watched his daughter speak for the first time, reciting the laws that applied to their circumstance word-for-word.

By following her precisely planned morning routine on her first day as a new attorney at Hanbada Law Firm, Young-woo shows us how she has learned to adapt to the world around her two decades later. To say she is passionate about whales in addition to the law would be a grave understatement.

She is a living library of esoteric whale information, with images of these marine beasts adorning everything from her room slippers to her framed portraits. To avoid being surprised by new flavors or textures, her father creates a unique “Woo Young-woo kimbap” for her, in which all the ingredients are meticulously wrapped between layers of rice and seaweed. This allows her to see exactly what has been added within.

Young-woo’s life, unfortunately, isn’t always as irrational as whales and kimbap. As an adult, she experiences a variety of forms of ableism daily. The most startling behavior, though, comes from her new boss, attorney Jung Myeong-Seok (Kang Ki-young), who isolates her as soon as she exhibits any evidence of her neurodivergence.

He is fearful enough to request a meeting with the CEO of the law company despite her obvious qualifications and suitability for the position. He even goes so far as to say that CEO Han’s (Baek Ji-won) judgment should be questioned since “she’s different from me.”

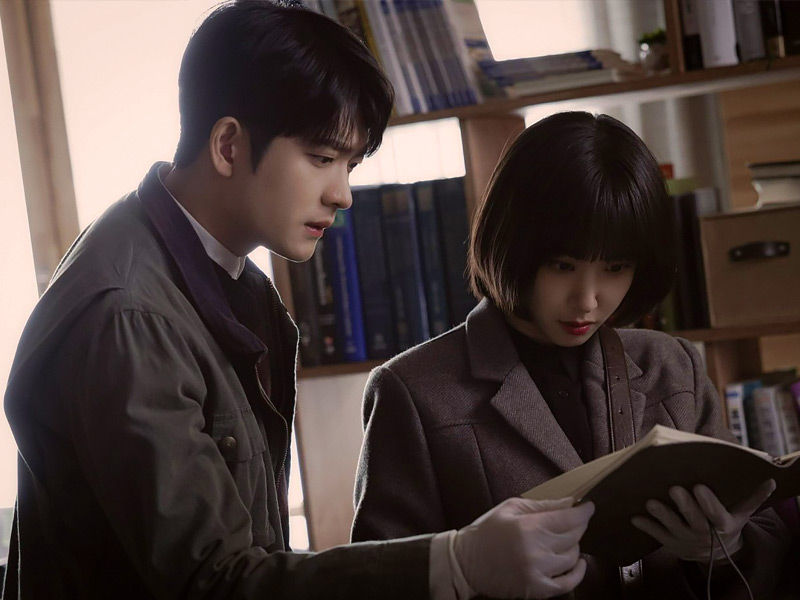

Of course, despite the odds, Young-woo consistently succeeds. She stands up to the plate with her perfect recollection of the law and case documents to fill in any gaps in her first case as a Hanbada attorney that even her superiors had missed, despite Myung-oversight Seok’s of her legal competence.

She was given the chance to disprove the legal abilities of Myung-Seok and her firmmates, but she also succeeded in clearing her elderly client of a false murder accusation.

Extraordinary Attorney Woo‘s approach to this typically uninspiring genre as a legal procedure is unique. In contrast to many of its legal K-drama predecessors, which have dabbled in dramatic, unrelenting examinations of ferocity in the courtroom, this series opts to cast a cheery light on legal issues as seen through Young-woo’s naïve eyes.

The main plot of Extraordinary Attorney Woo drives the character development of Young-capacity to woo’s to adapt to each episodic case and client’s unique circumstances. The challenges she faces, such as jealous coworkers or a nasty opposing attorney, are unable to deter her from her unwavering passion for and dedication to her work.

Park Eun-portrayal bin’s of Young-woo, an autistic character whose representation is uncommon within the stratosphere of Korean entertainment itself, is noteworthy evidence of her acting prowess.

If there is anything to be said about Extraordinary Attorney Woo, it is that Young-woo’s characterization tends to lean towards the former. Media portrayals of autism spectrum disorder have always been a toss-up. They are either glorified as socially awkward yet misinterpreted geniuses with savant-like abilities, or written off as flat secondary characters written in to display the uglier, undesirable sides to ASD.

Also read: The Gray Man: Despite its charismatic leads, the film falls short of expectations

Two episodes in, the show is already implying that neurodiverse people are expected to be able to make up for their unpleasant features by being natural-born prodigies, which is not wholly unlike what many underrepresented minorities experience in both fiction and reality.

It may be too soon to forecast the depths that Extraordinary Attorney Woo author Moon Ji-won would be willing to delve into, but there is still plenty of room to do so. As readers, all we can do is hold out hope that this space will be effectively utilized.

The humor and lightheartedness of Extraordinary Attorney Woo rarely require viewers to have a legal or ASD background to enjoy it. It provides an opportunity for those of us, including the people Young-woo comes into contact with, to examine our own actions and preconceived notions regarding neurodivergence.

Even though the show’s portrayals of ASD sufferers are not fully faultless as of now, the fact that it fosters acceptance and understanding for them is reason enough to celebrate.

Every Wednesday and Thursday, new episodes of Extraordinary Attorney Woo are made accessible on the South Korean streaming service ENA as well as in some areas on Netflix.