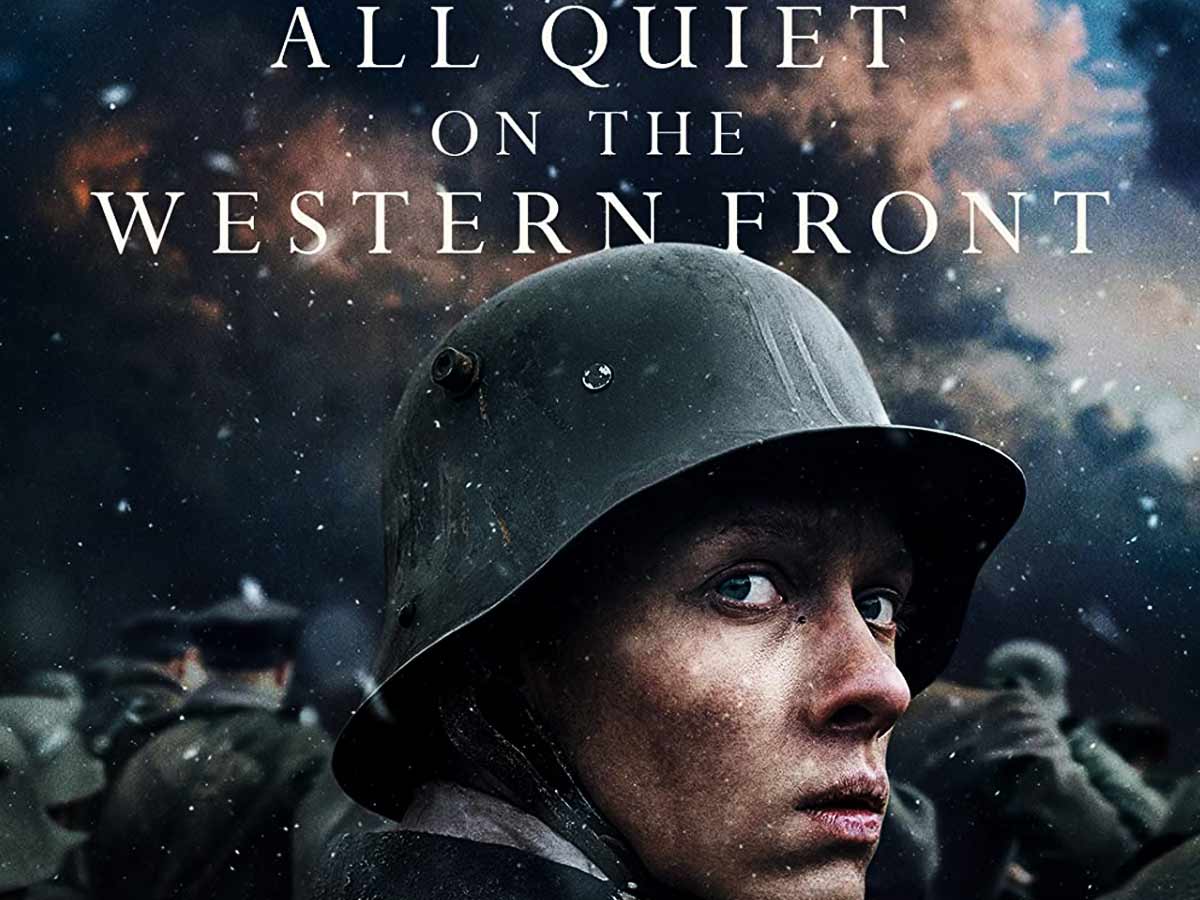

All Quiet on the Western Front’s depiction of the traumatic experience of World War I is perhaps as dark and cruel as any that has been committed to film. While there have been dramatic prior versions of Erich Maria Remarque’s lasting 1929 novel that also emphasized how there is no valor or glory in such conflict, none have been exactly like this.

It is a film filled with righteous anger in a manner that none of the previous adaptations have done, alternating between the graphic violence of many young men being slain one after the other and the chilly loneliness as the survivors sit about waiting for their time to die.

All of these adjustments are required for this vision to be achieved.

Those previous films, one from 1930 and another from 1979, mirrored the cinematic techniques and environment of the time while remaining committed to depicting the awful reality of war. This newest adaptation from writer-director Edward Berger follows much of the same course as the other stories, but in a unique way that eliminates numerous narrative strands from the original material while introducing some key new ones.

With these changes, it becomes a work that is disillusioned with the notion that a mere understanding of the horrors of war will have much of an influence in stopping them. While undeniably cynical, the film’s dismal realism in this new approach is refreshing in the silent wrath that simmers underneath it.

After more than a century, there is little evidence that depictions of the inhumanity of such combat have even made a dent in the depravity that drives them. The film engages in a cinematic debate with the tradition of anti-war art and is significantly less fascinated with the promise that exposing the truth of what wars are like could somehow prevent them from occurring.

The issue it depicts is one of nationalist-fueled cruelty, not a shortage of knowledge since those peering down from their safe and warm towers have enough insight about what is going on. The finest adaptation of the story to date reflects a creative outpouring of wrath at how people in authority are well aware of the fate they are putting men into.

The film continues to follow the novel’s major character, Paul Bäumer (Felix Kammerer), who is thrown into the pandemonium of the front almost immediately. Explosions and gunfire are incessant as we approach the point where millions will perish battling for years over a few hundred yards. It discards all training and any semblance of order felt at the start of the narrative to immerse itself in chaos. Men are driven insane, while others retreat deeper into themselves to live.

The only reprieve comes when Berger depicts nature in peace, as though we are offered a glimpse of what may be if such a battle did not exist. These periods of calm are fleeting, but their juxtaposition with how devilish the violence is becomes poignant. The destruction is portrayed as unnatural and an insult to the surrounding world, which is swallowed up.

Even when distant from the front, the echoes of the conflict cannot be completely avoided. The guys here are always aware of what is going on and are aware of what awaits them when they are returned to the depths of this Hell on Earth. Whereas the book and previous films framed such a dilemma as a result of a lack of greater awareness of how horrible it is to be there, this work goes a step further. This starts with Paul not being granted permission to see his family. This is the most notable departure from the original material and signifies a shift in the film’s focus.

Characters at higher levels of military and civilian authority, in particular, speak frankly about what is going on. All of these individuals are absent from the novel, and their presence at important periods during the film demonstrates Berger’s argument. He shows us those who can halt the violence and misery that is engulfing thousands of people every day that they wait.

The only figure who appears to care about this is Daniel Brühl’s Matthias Erzberger, a new character who did exist in history, who is urgently attempting to stop the battle so that the never-ending death can be ended. He is, however, an aberration who helps to highlight how indifferent and frigid virtually everyone else is around him. Despite his efforts to change the course of the fight, his cries for peace come much too late for the millions who were led to their deaths by people who were fully aware that they would perish. Paul is the face of this, but numerous more guys were treated as if they were nothing.

Even the outfit he wears was abandoned with his name tag after someone was slain immediately before him.

The key role in this is a General who enjoys lavish dinners as people beneath him perish in the mire. It is a recurring theme in the film, with those in authority feasting in safety before cutting back to the soldiers on the line waiting in quiet before being transported to murder.

This is the wrath that, while prevalent throughout the novel as the guys discussed the dispute amongst themselves, reaches a boiling point here. While ordinary people may not have recognized the entire scale of the conflict as distorted by propaganda or could halt it on their own, those in control knew.

Every command to send the men over the wall and into a charge that would end with them being ripped apart was made by people who understood the consequences. The portrayals of this in the film, notably one long section near the midway mark, illustrate a reality that was well-known to those who made the decision. They did so well cognizant of what would occur and the resulting consequences.

There is no reason or apology for these decisions, which repeatedly pushed men through a meat grinder. The “real face” of the conflict was one in which they had all been looking and sending soldiers to die.

So, what is the function of anti-war films, or anti-war art in general? Is it to shed light on the truth and expose what truly occurs so that we can learn not to repeat it? This idealistic assumption is based on the notion that the only reason wars occur is due to a lack of understanding of the human cost of conflict. What the most recent All Quiet on the Western Front reveals is that not only is this not true but that most of those with the authority to take countless lives do so without hesitation.

Also read: The Good Nurse: A Extraordinarily Thrilling Movie by Netflix

Trying to extract sympathy from individuals who have none to give will always result in the same results. The film, while not celebrating such a struggle as one might wish, also recognizes that it is all for naught. This is made obvious in Paul’s finale, which is enlarged from the novel and drastically different from any previous adaptations. It adopts a more gloomy poetry that converses with its forefathers, since each, no matter how uncompromising, has not changed the basic ways that the war machine’s gears will always keep moving with the strong controlling the levers.