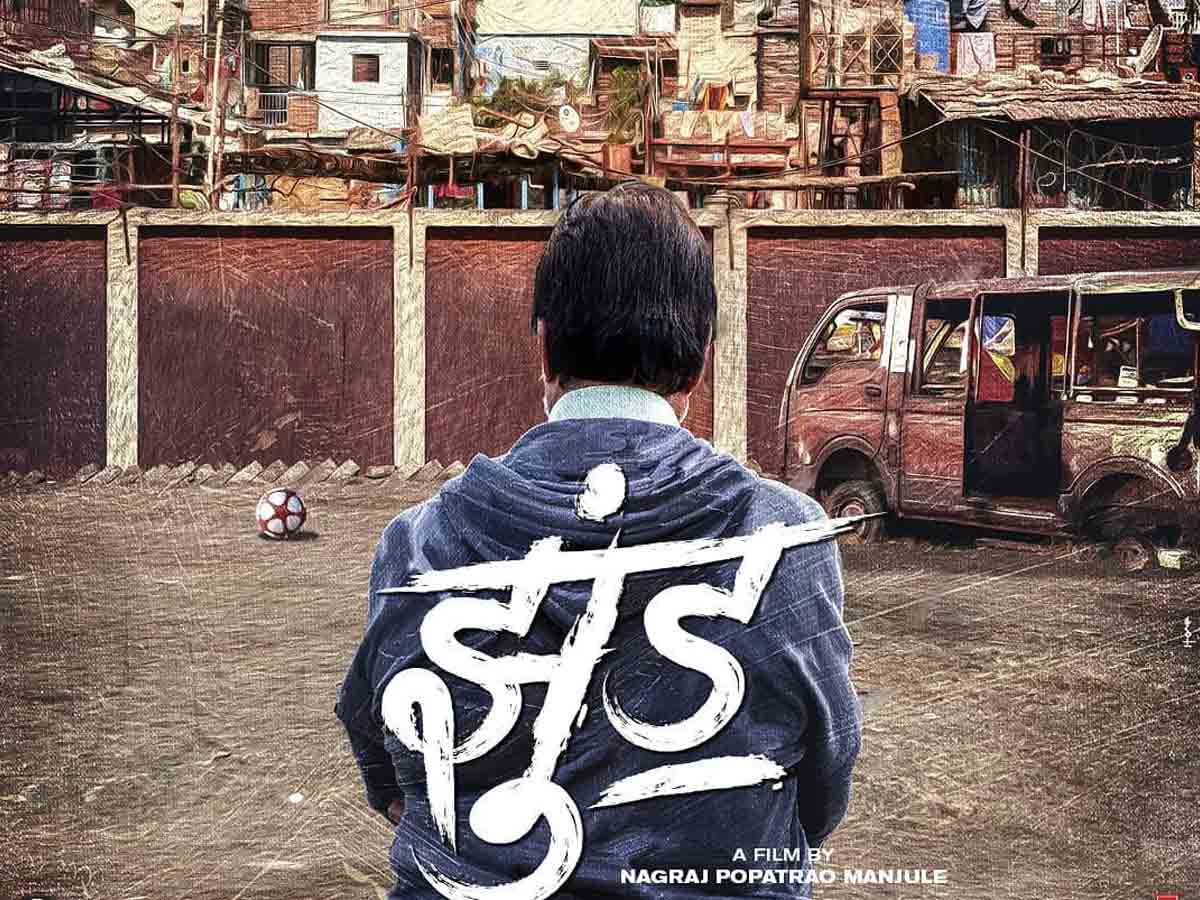

The inspiring true-life narrative of Nagpur-based Vijay Barse, who created Slum Soccer, an NGO that works tirelessly with slum children, serves as the inspiration for writer-director Nagraj Popatrao Manjule’s latest film, ‘Jhund.’

Because of his past, which he employs so honestly in his work, you’d assume there’d be no one better than Manjule to ace this type of picture.

He gave us ‘Fandry’ and ‘Sairat,’ two of the most profoundly moving films about severe caste distinctions and brutal societal mores. . The Jai Bhim shouts and Babasaheb Ambedkar posters that abound in a furious dance scene set to Ajay-Atul’s rhythms in ‘Jhund’ are unmistakable signs of the Dalit component among the slum residents. Manjule is also the casting director. Therefore, the faces appear natural, as opposed to many Bollywood films in which performers wear brownface to blend in with their surroundings.

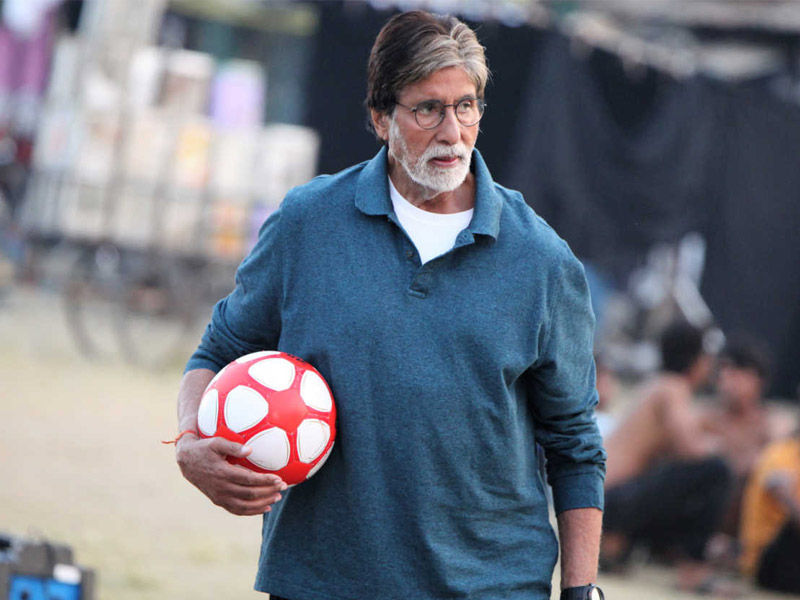

The guards chase the residents of the neighbouring slums away from the exclusive grounds of St John’s College because they do not want any contact with the young people who spend their time sniffing glue, chain snatching pick-pocketing, and pick-pocketing. The’slum youngsters need a saviour, and who is better than senior sports coach Vijay Borade (Amitabh Bachchan), who is about to retire from the local college?

He focuses his attention on this disadvantaged sector. He builds them up to be able to compete with the la-di-dah youngsters and be invited to a global championship league in faraway Hungary.

This motley crew, all confident and heartbreakingly worldly-wise despite their youth, is the greatest aspect of this picture, which makes us fight hard for its sweet moments throughout its infernally lengthy three-hour runtime: you’re at risk of falling out of the movie even before you’ve truly gotten into it.

Also Read, Against the Ice: Explore the Amazing Expedition through the Ice

Some children have moms who work as domestic helpers in large houses, leaving them to fend for themselves – picking rags and collecting rubbish. I like their portrayal because, despite having such difficult circumstances, they are not seeking pity. All they want is a shot at a brighter future, and Borade is the ideal lighthouse.

But the film can’t decide whether to make Bachchan’s Borade a hero or focus on the hardscrabble existence of the slum youngsters and their battle to overcome the enormous obstacles they face from a hostile police force and an equally hostile savarna samaj that wants to keep them hidden. This yo-yo effect doesn’t help the picture, which alternates between being a sports film, a biopic about an unexpected hero, and a group of poor young people on the path to upliftment via athletics.

There are just too many abrupt changes of heart in the story. A single Muslim family is crammed in, to be used as an example: the guy, who has been a long-time jerk — to his wife and girls — comes all over remorseful. The ultra-violent police force becomes a facilitator. Borade’s adult son, with bitterness written all over his face due to his father’s obsessive connection with the ‘basti’ youngsters, turns over a new leaf.

The narrative has far too many sudden changes of heart. To offer an example, a single Muslim family is squeezed in: the husband, who has been a long-time jerk — to his wife and girls — comes all over regretful. The ultra-violent police force transforms into a conduit. Borade’s adult son, who has bitterness written all over his face due to his father’s obsession with the ‘basti’ children, turns over a new leaf.

The two leads of ‘Sairat,’ Akash Thosar and Rinki Rajguru, are here. Both are used as ‘types’: the former, who despises the slum gang’s leader, Don aka Ankush Masram (Ankush Gedam), and the latter, who is the most interesting and detailed of the ‘slum kid’ ensemble, with his wild man bun, hard exterior, and soft heart. How dare They turn around and stare us in the eyes?

Rajguru is a footballer who must jump through bureaucratic hoops to obtain a passport. Hers is the marginalized household that does not have a ‘kaagaz,’ and moments of unexpected laughter arise when she and her father approach a prominent member of their town for a ‘pehchaan patra’ (a letter of recognition). How can a guy like this ‘recognize’ the people who live beneath his gaze?

Kishor Kadam, who portrayed the leader of a dirt-poor Dalit family forced to live on the outskirts of the village in ‘Fandry,’ is cleverly played against type as Borade Sir’s colleague who is vehemently opposed to this blending of class and caste. These characters would have worked better in an anthropological inquiry; in a feature picture headed by a superstar, these individuals’ innate drama and situations goes off-key.

Finally, ‘Jhund’ is an overlong meander, with its sometimes vibrant moments drowned out by the most conventional rhythms of the sports as upliftment film. The finest intentions do not necessarily result in a terrific film.