Baahubali should be mentioned in this Indian movie’s review for the second time this week. Despite its political issues, S.S. Rajamouli’s Telugu smash was such a significant piece of Indian cinema that it is only natural for filmmakers and critics to use it as a benchmark. But neither of these two recent albums is an homage.

While Karan Malhotra’s Shamshera (Hindi) dramatically overturns the supremacist status quo of Rajamouli’s franchise even while borrowing its basic story template and larger-than-life expensive packaging, Abrid Shine’s Mahaveeryar (Malayalam) is a parody of the mythic-fantasy genre that many writers and directors have tried to replicate since Baahubali’s success.

Shamshera begins with a voice-over and images that describe how the Mughals enslaved a particular group of Rajputana residents who fled the invading force and moved to another region of India. They are exploited, degraded, and marginalized in their new home. They are “neech jaat,” or “low castes,” to use the words of the main antagonist of the movie.

Shamshera, a representative of the downtrodden Khamerans community, is portrayed by Ranbir Kapoor. In Shamshera, two generations of his family in the 19th century battle the repressive upper castes of India and the British colonizers for their azaadi.

The Mughals are just briefly depicted in Shamshera, which is the first surprise. This dynasty and other Muslim communities have recently been frequently portrayed in mainstream Hindi cinema as the epitome of violence against helpless Indians, embodying bloodlust and betrayal to the point of distorting actual historical situations in which Muslims fought the British Raj while other Indians sided with the white colonizers.

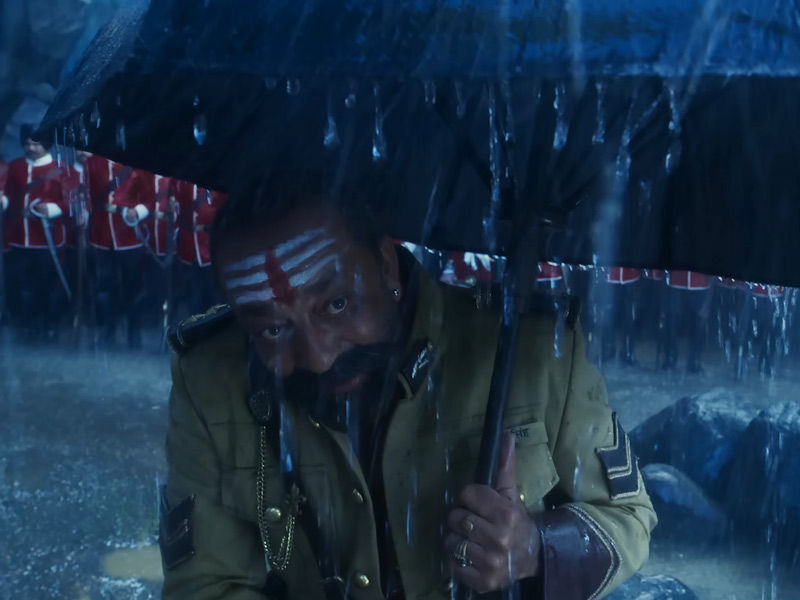

Look no farther than the nefarious Kesari, starring Akshay Kumar. Thankfully, Shamshera does not glorify the Mughals’ military campaigns but rather emphasizes the betrayal of people who would be regarded as “us” in the prevailing current socio-political discourse. The delectably named Shudh Singh, played by Sanjay Dutt, stands for that treachery.

The most unexpected caste-system critics to emerge from mainstream Hindi cinema are Shamshera and his son Balli (both played by Ranbir Kapoor). With all the trappings of massy cinema that Bollywood lovers are accustomed to and some more, including solid acting, for the most part, Mithoon’s energizing music, lively dances, spectacular sets and costumes, lush natural scenery, good-looking lead actors, and the amazing Anay Goswamy’s cinematography desi, Malhotra’s film is the best education on how caste politics affected India’s equation with the British imperialists that you could hope for in Shamshera.

In Shamshera, Ranbir is stunning in every aspect possible, including his acting, sex appeal, dancing, litheness in the action sequences, and engaging charisma.

But its writers are the real stars of this never-ending display of grandeur and substance: Nilesh Mishra and Khila Bisht wrote the story, together with the director (who previously directed Agneepath), Ekta Pathak Malhotra wrote the script, and Piyush Mishra wrote the language.

This doesn’t mean that Shamshera’s worldview can’t be criticized. In no way. For starters, Sona, played by Vaani Kapoor, has no purpose other than to be Balli’s lover, the object of his desire, and—for a brief moment in the second half—his partner in the battle against Shudh Singh.

The only significant female characters are concerning the male protagonist, one as his mother and the other as his romantic partner. She is ultimately simply a glamorous sidelight and unavoidably objectified in a masculine cosmos where all the action is in the hands of men.

Also read: Shabaash Mithu: A Bold New Cricket Biopic Starring Taapsee Pannu

In its attempt to expose upper-caste harshness, the movie is paradoxically excessively kind to the British, maybe because doing so would need more depth than the current script allows for.

And while it is wonderful that Shamshera flips Baahubali’s regressive politics on their head, the writers may want to think twice about why they felt the need to depict Khamerans bowing down to their chosen leader and his bride in a movie that, on the whole, rejects subordination and encourages rebellion.

These are regrettable weaknesses in a movie that deserves a standing ovation for several reasons. Shamshera is a scathing indictment of the caste system that is unique for a mainstream film and places the topic front and center in a Bollywood that has for far too long primarily avoided discussing caste.

An example would be Dhadak, the awful Hindi remake of the fantastic Marathi blockbuster Sairat. Shamshera acknowledges and reiterates its conviction that crimes against the caste are just as abhorrent as those committed by an outside power. It is worse if anything.

Being so full of courage and conviction makes it able to overlook some of this movie’s excesses, eccentricities, and aesthetic similarities to prior iconic movies.

The railway robbery in Shamshera, for example, is wolf whistle material, although the special effects could have been better. Overreacting Sanjay Dutt.

And it’s ridiculous how the hero somehow recovered after getting stabbed in the upper torso. In a movie where a key character asks, “Is there a larger mask in this world than religion?” and where the word “shudh” is used in association with the name of a caste that is regarded as lowly, at least these concerns can be overlooked.

Kudos to Karan Malhotra and Yashraj Films! Well done, Team Shamshera.