Metaphysics is a branch of philosophy that studies the first causes of things and the nature of being in antiquity and the Middle Ages. However, in post-medieval philosophy, many other topics were grouped under the umbrella term “metaphysics.” Let’s know a little more about Metaphysics in this blog.

METAPHYSICS: NATURE AND SCOPE

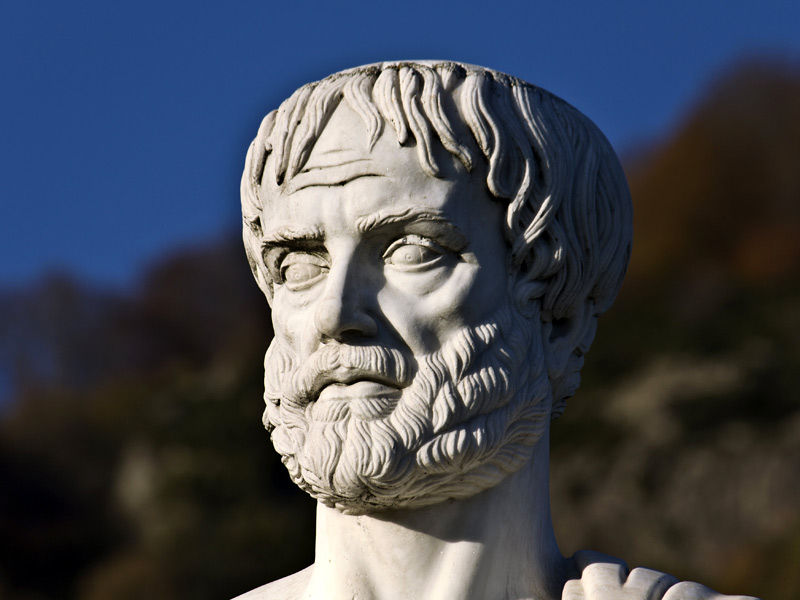

Aristotle, a Greek philosopher, wrote a treatise on what he called “first philosophy,” “first science,” “wisdom,” and “theology” in the fourth century BCE. Ta meta ta physika, which roughly translates as “the ones [i.e., books] after the ones about nature,” was given to that treatise by an editor of his works in the first century BCE. “The ones about nature” relate to the books that comprise what is now known as Aristotle’s Physics, along with his other texts on the natural world.

Metaphysics is not associated with the quantitative science, which is now known as physics; but is concerned with philosophical issues concerning sensible and mutable (i.e., physical) objects.

The title “Ta meta ta physika” conveyed the opinion of the editor that students of the philosophy should start their study of first philosophy only after mastering the Physics. Metaphysics, derived from the Greek title is the Latin singular noun, has been and was used as both the title of a treatise of Aristotle and the name of its subject matter. Hence, the result is, the root of almost all metaphysical words in Western European languages is metaphysics (for example, metaphysics, la métaphysique, die Metaphysik).

Also Read, MetaVerse: The Digitally Amazing Way of Life of the Future

First philosophy, according to Aristotle, is the study of “being as such” and the study of “the first causes of things”. The relationship between these two definitions is a hotly debated topic. Whatever is its answer, it is already clear that the subject matter of what is now known as metaphysics cannot be identified with the concept of Aristotle’s Metaphysics. While it is true that all the problems addressed by Aristotle in his treatise are still classified as metaphysical, the term has been applied to a much broader range of issues since at least the 17th century.

Indeed, if Aristotle could examine a modern-day metaphysical textbook, he would classify much of its content as physics, as he understood the latter term. To take just one example, a modern book would almost certainly include a substantial discussion of philosophical issues concerning the identity of material objects.

The following is an old example of a similar problem: Molten gold is poured into a mould to create a statue. The statue is then melted, and the molten gold is poured into the same mould before cooling and solidifying. Is the finished statue identical to the original? Such problems clearly do not concern with being or the first causes of things.

PROBLEMS IN METAPHYSICS

Although sensations are mental events, they appear to most people to be a reliable source of information about a nonmetal world, the world of material or physical objects that comprise the perceiver’s environment. Many philosophers have attempted to answer the following related questions in relation to that “external world”: Is there a world outside of the universe? If so, can the senses provide reliable information about it?

If they do, do humans know — or can they learn — about the outside world? If they can, what is the source or foundation of their understanding? Attempting to answer such questions is addressing the issue of external world reality.

That is a modern (i.e., postmedieval) philosophical problem; no ancient or mediaeval philosopher considered any of the questions raised in the preceding paragraph.

It was not widely known until the work of the Anglo-Irish philosopher George Berkeley (1685–1753) that it was regarded as fundamental or especially important—that is, as a problem that every philosophical system with any pretense of comprehensiveness was obliged to address—after it was first explored by the French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650).

Very ingenious and capable arguments for a comprehensive form of idealism in which nothing exists except the ideas (i.e., sensations and mental images), things composed of ideas, and the minds within which ideas exist were developed by Berkeley.

Berkeleyan Idealism

Although Berkeley rejected the existence of anything other than ideas, things made of ideas, and minds in which ideas exist however the existence of objects such as “the pen in his fingers,” “the body Descartes animated,” and “the paper and writing table before him” was not explicitly denied by him. Berkeley, on the other hand, acknowledged the existence of those objects while insisting that they were made up of ideas. His case was naturally forward.

IS METAPHYSICS POINTLESS?

Some irreligious atheists, such as logical positivists, have argued that metaphysics’ agenda is largely meaningless and incapable of producing any results. Metaphysical statements, according to them, cannot be either true or false; as a result, they have no meaning and should not be taken seriously. This viewpoint has some merit, but it is unlikely to persuade or impress religious theists who place a high value on metaphysical claims. As a result, the ability to respond to and criticize such claims can be useful.