Writer-director Freaky and Happy Death Day 2U by Christopher Landon brilliantly operate as Trojan Horses: breezy horror-comedies used to quietly smuggle in tangible levels of sadness dealing with familial issues. We Have A Ghost is no exception; nonetheless, it includes a tad more heartbreaking sorrow to accompany its wacky antics. Or maybe it just feels that way as we reach the dramatic climax two hours into this story of an uprooted family discovering a lost soul trapped in limbo. Taking tone cues from Beetlejuice, it makes a precarious transition from a short tale (Geoff Manaugh’s “Ernest”) to a full-fledged film. What should be a quick 90-minute commitment becomes a much lengthier commitment that, while passionate, is far too slow for its own benefit.

Kevin Presley (Jahi Winston) has recently moved to the Chicago suburbs and is dissatisfied. Not only is the Victorian-era mansion in obvious ruin, overrun with vines and cobwebs, but he also believes he is a victim of circumstance as a result of his father Frank’s (Anthony Mackie) unsuccessful get-rich-quick schemes. This has also caused Kevin’s older brother Fulton (Niles Fitch) and mom Melanie (Erica Ash) to be concerned about the family’s new beginning. But their anxieties will be allayed when Kevin finds someone special—and no, it’s not next-door neighbor Joy (Isabella Russo), a tech-savvy, Manic-Pixie-Dream-Girl-like love interest. She is not the one who rocks his world.

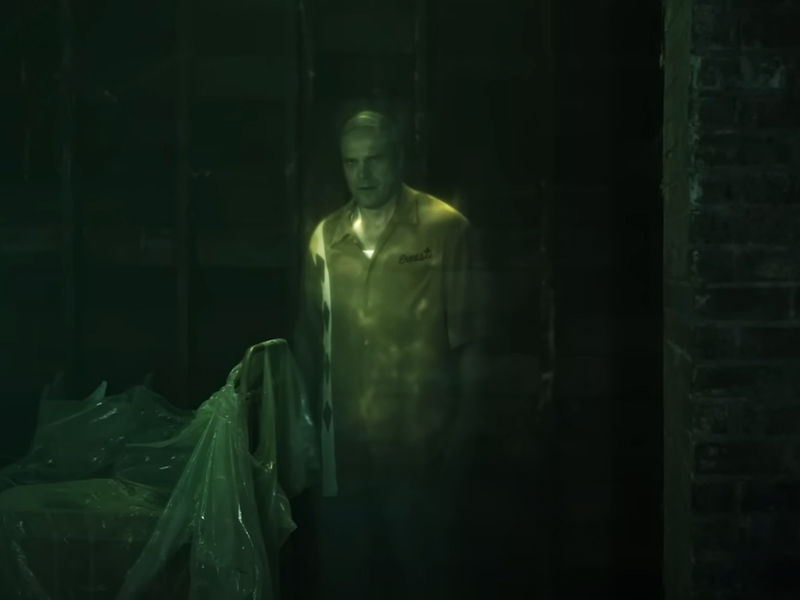

Ernest (David Harbour) is the balding, bowling-shirt-wearing middle-aged ghost that haunts the Presleys’ attic. Ernest befriends Kevin when the specter’s effort to frighten him fails.

Kevin thinks that his new bestie is trapped between realms and requires assistance with some unfinished business. Ernest has amnesia and can’t communicate effectively, so it’s unclear what that implies. Meanwhile, Frank and Fulton have learned of Ernest’s growing connection and are attempting to exploit him online, publishing videos, selling souvenirs, and booking ill-advised TV appearances. As a terrifying social media following grows, Ernest’s presence notifies authorities such as Dr. Leslie Monroe (Tig Notaro) and CIA Deputy Director Schipley (Steve Coulter), whose malicious goals include studying Ernest and impeding his desire for peace and crossing over.

To say this feature is cramped would be an understatement. It’s brimming with fantastic ideas, but far too many of them aren’t used in a creative way that saves time. Scenes establish one thing at a time, parceling out information and emotion when they should be connected, rather than pulling double or triple duty, concurrently layering in the characters’ internal and external stakes among the humor, action, and spectacle. Having Kevin a clever, witty companion like Joy to whom he can confide is a wonderful touch, but it is ultimately unnecessary because Ernest draws him out of his shell in similar ways. Eliminating other unnecessary elements, particularly those involving the vendetta-driven Dr. Monroe and the CIA, in favor of our key characters’ objectives, might have helped tighten the pace and dynamic rhythms.

Nevertheless, the events in the short tale have been modified for the welfare of the characters, softening Frank from a one-dimensional, self-centered guy to an imperfect parent working through his problems, and altering the boys’ personalities and arcs. The story benefits from structural modifications as well, changing to a cleaner, crisper style and centering on a younger protagonist, which amplifies the Amblin-inspired shenanigans. The incorporation of big action moments is justified, from the crackling police pursuit when the kids hit the road with Ernest to Ernest’s body-contorting, face-melting meeting to medium Judy Romano (played by a vivaciously unhinged Jennifer Coolidge).

Also, Read Sharper: A Delightful Caper Concerning Fraudsters And The Super-Rich Is Led By A Fine Cast

A warm, lighthearted buoyancy is expertly blended not only with the script’s comic flexing but also with Marc Spicer’s saturated photography and Jennifer Spence’s production design choices, particularly the autumnal-colored stained-glass window that revels in its plethora of cinematic moments. While Mackie and Winston’s performances beautifully paint their father-son relationship dynamic, it’s Harbour’s subtle, wordless work that stands out, probably because he was given the more difficult challenge of acting without any language and without going too wide.

Despite the film’s clear-eyed aims, unnecessary aspects bloating the original material combine in the film’s interminably protracted second act, which is subsequently followed by an explanatory, awkwardly built ending. Of course, closure is inevitable, but at a low cost that significantly diminishes the effect of its key characters’ travels. It is extremely disheartening.