The third film in Joanna Hogg’s sort-of trilogy, which also includes The Souvenir I and II, investigates the hauntings of relationships by focusing on the one that stays the longest in the other: that between a mother and daughter.

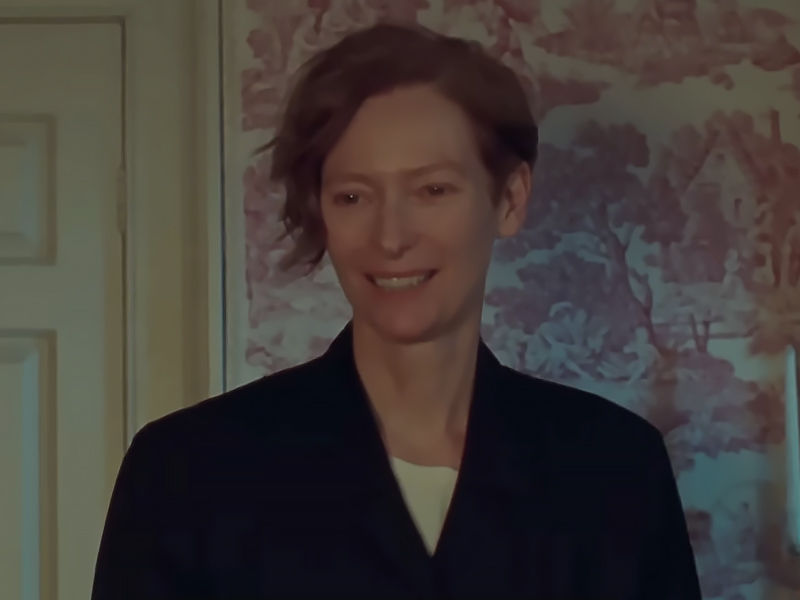

Here, Tilda Swinton plays both Julie Hart and Rosalind, her mother.

Julie, a filmmaker, picks a secluded 18th-century castle-turned-hotel where her mother spent a chunk of her previous life to spend some peaceful time together, speak about memories, and usher in her birthday – and get it all on her phone recorder (in secret), and her camera.

All they have at this castle, which is located down a bleak road with the wind whistling through the branches, is the mist that obscures, creaking doors and windows, things that go bump in the night, and an almost arrogant receptionist (Davies) who would rather be rushing off every night with what appears to be her boyfriend, who drives in music blasting loud techno music.

As the taxi driver tells Julie a story about a face in the castle window, she stops every night to look – and sees something. A fluttering white curtain or a pale face might be the culprit.

Julie is unsure from the start. Is the film she’s attempting to create a work of love or exploitation? Is it her right to share her mother’s privacy and story? And, as Rosalind recalls both pleasant and painful events at the castle previously held by an aunt (including the loss of a brother and a miscarriage), is Julie correct in bringing her here? Is she attempting to assist herself or her mother?

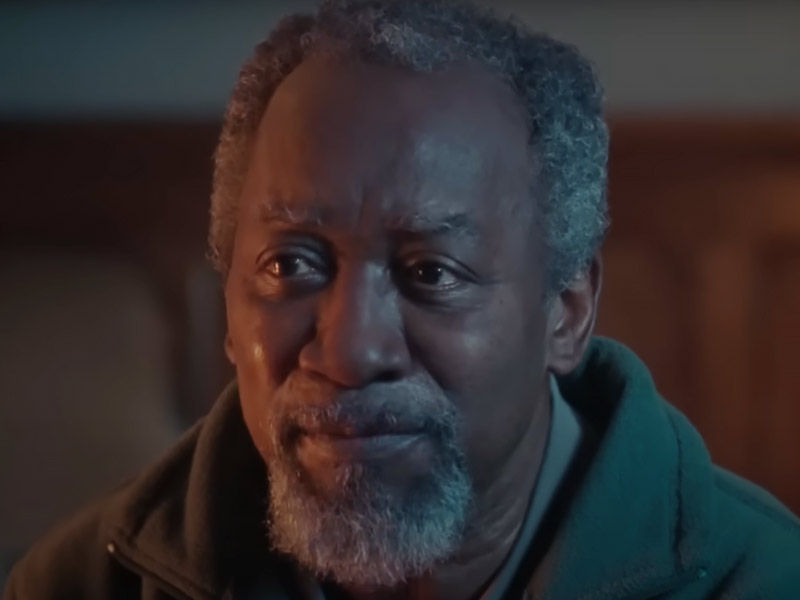

The location, which may or may not be haunted, the receptionist, who may or may not know more, the groundsman, who may or may not be real, and their dog, who may or may not be whimpering, all contribute to Julie’s cloak of grief.

We almost intentionally hope our parents were happy and carefree as children, knowing we can’t make things better but also knowing that in them resides a world that was once our cocoon. A crack here may be the end of that parallel, non-existent universe for us.

The location, which may or may not be haunted, the receptionist, who may or may not know more, the groundsman, who may or may not be real, and their dog, who may or may not be whimpering, all contribute to Julie’s cloak of grief.

We almost intentionally hope our parents were happy and carefree as children, knowing we can’t make things better but also knowing that in them resides a world that was once our cocoon. A crack here may be the end of that parallel, non-existent universe for us.

As parents, we understand the weight of that expectation, which only grows greater as mortality drags us away. Apart from the changes between the two ladies, very nothing happens in this mood-driven picture. Is Rosalind clearly shrinking from the effort as Julie’s determination to make her mother happy, to give her the perfect birthday, grows?

Also, Read Pop Kaun: Satish Kaushik’s Most Recent Tv Programme Has A Good Heart But Falls Short In Execution

In contrast, the groundsman’s love for his recently dead wife is a cheerful love free of guilt but filled with memories that, in his words, “has begun a new chapter.”

Rosalind expresses sadness that Julie has never had her own children, adding that she still considers herself to be a “perfect mother” and has always cared for her. “She is fantastic at practical love,” Rosalind adds. “She’s quite good at it.” Her selection of “dos” for love is intriguing. And that says everything.