It’s easy to roll one’s eyes at films like The Last Bus. These are films that appear to have been tailor-made for those Tuesday morning screenings where guests are served a cup of milky tea and a custard cream on the way in – soothing, nostalgic, and ultimately unchallenging. That’s a reductive analysis I’ve certainly used in the past. Still, perhaps a year of confinement has triggered something in me.

At the end of The Last Bus, I didn’t simply have a lump in my throat, and it was present the entire time.

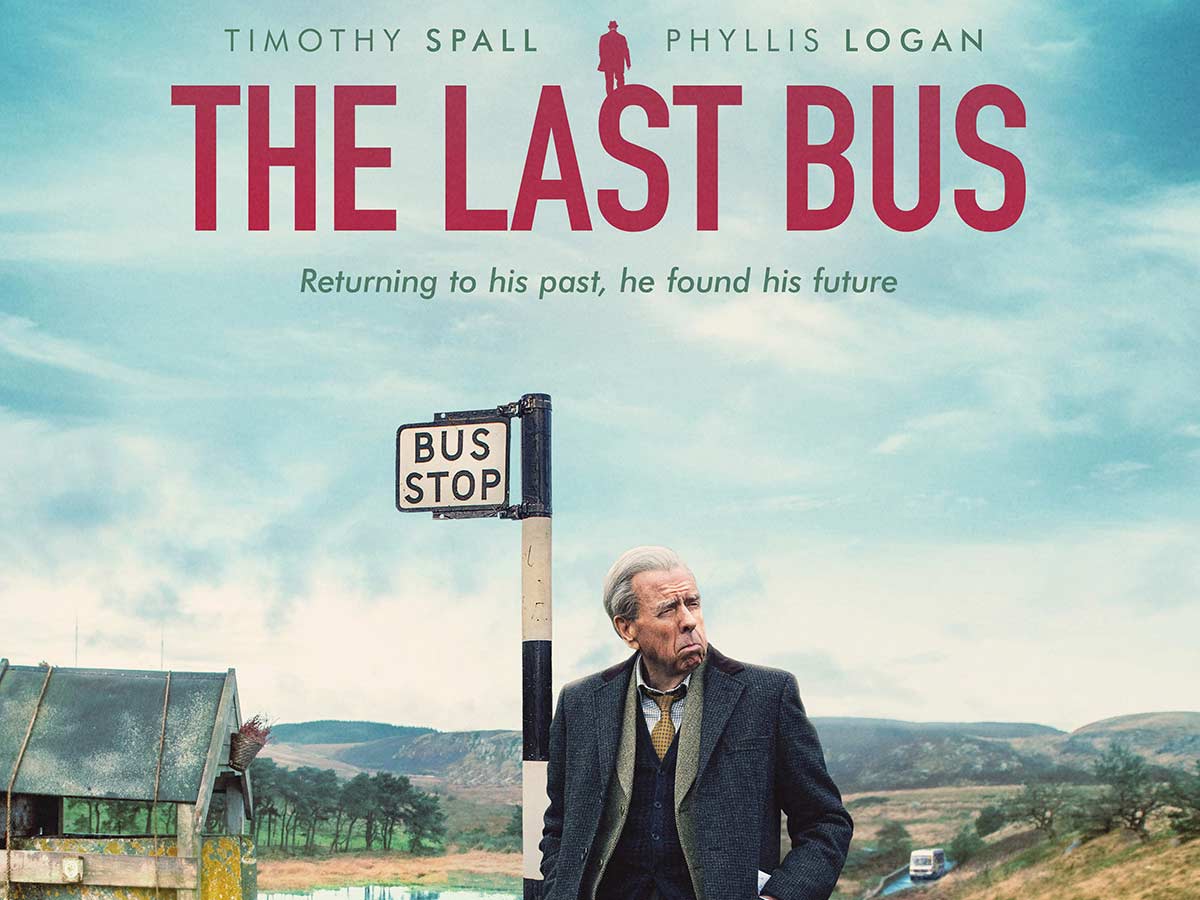

Much of this is due to Timothy Spall’s outstanding central performance. With admirably tired physicality, he adds at least 20 years to his age to play Tom, a Second World War veteran reeling from the cancer death of his wife Mary (Phyllis Logan). We discover from flashbacks that the pair abandoned their home of Land’s End in the 1950s following an undisclosed tragedy, with Mary pleading with Tom to get her as far away from the sorrow as possible.

As a result, the couple boarded dozens of buses and spent the rest of their lives at John O’Groats. With a promise to Mary still ringing in his ears, the elderly Tom tries to reverse the journey.

Also Read, Hey Sinamika: A Cool Breezy Comedy without a Soul

Spall delivers every detail of this story with the polished competence we’ve come to expect from him. His portrayal of the increasingly feeble retiree is neither caricatured nor over-played, with subtle groans and stumbles enough to give the impression of a man carrying the weight of a lifetime on his shoulders. His deteriorating health is rarely used for humor, with director Gillies MacKinnon – whose most recent effort was the 2018 TV movie Torvill & Dean – and veteran British television screenwriter Joe Ainsworth portraying the narrative with sensitivity at its heart.

Wisely, MacKinnon’s film rarely departs from Spall’s character’s point of view, but it appears to be in a tug of war with itself over its thesis. It’s at its best when it concentrates on his drive to keep his commitment to his wife. However, it occasionally gets bogged down in episodic sketches in which he encounters icons of diverse and multicultural Britain. Notably, people around Tom are challenged by this diversity, not Tom himself. When Tom intervenes to defend a woman in a niqab who is being sexually harassed and racially attacked, it feels somewhat perfunctory – albeit admirable – given how little it ties to the story’s central theme.

A story thread in which Tom quietly becomes a social media celebrity, on the other hand, gently bubbles beneath the surface of the narrative. It’s never intrusive and only appears in half-heard radio broadcasts and brief shots of fellow passengers typing the hashtag #BusHero into Instagram. Still, it feeds into a rousing and life-affirming finale that shows modern British society’s community spirit and diversity at its best and most heart-warming.

It just takes a basic understanding of movies like this to figure out where The Last Bus is going, but it would take a fairly dark heart not to be moved by the voyage. Spall draws pity with every creaking footstep or garbled word of thanks to the friendly individuals who help him on his route, and this is enough to make up for a story that’s as ancient as the lovely hills and country lanes Tom rides through. The film is unlikely to surprise you, but it will undoubtedly delight you to pieces.