“Oh, I don’t know. Life is interesting, I guess.” So articulates Andy Warhol, in his broadly hazy approach to saying everything and nothing immediately, numerous hours into

The Andy Warhol Diaries, another six-section narrative series debuting on Netflix on March 9.

Coordinated by Andrew Rossi (known for acclaimed narratives like Page One: Inside the New York Times and The First Monday in May) and created by Ryan Murphy (the hyper mind behind Glee, Nip/Tuck, Halston, and American Crime Story on O.J. Simpson and Gianni Versace, among numerous other vivacious and tasteless little screen issues), The Andy Warhol Diaries takes motivation from the doorstop of a diary distributed two years after the Pop craftsmanship star’s demise.

Perusers of the 840-page book, which comprises everyday recollections directed via telephone and altered somewhere around Warhol comrade Pat Hackett before distribution in 1989, run over a wide range of data. Some of it is numbingly cliché (recitations of insignificant tattle, records of dollar-sums spent on taxi rides). At the same time, some of it is outlandishly impressive (evenings out at Studio 54 with Bianca Jagger, meeting the Pope at the Vatican).

Part of the adventure of perusing the Diaries, for the individuals who observe it a rush by any stretch of the imagination, lies in figuring out how to accommodate one sort of disclosure with another sort that may be its inverse, such that makes the plain parts intriguing parts plain. The cycle can be viewpoint-changing for the individuals under Warhol’s influence. Watching one of Warhol’s long and trudging or even completely static films is refreshing and motivating.

As Warhol himself wrote in his book Popism: The Warhol Sixties in 1980,

“That had always fascinated me, the way people could sit by a window or on a porch all day and look out and never be bored, but then if they went to a movie or a play, they suddenly objected to being bored. I always felt that a very slow film could be just as interesting as a porch-sit if you thought about it the same way.”

That plain methodology presents a test to a narrative treatment of The Andy Warhol Diaries that appears to be unfavorable almost immediately when the ordinariness of such a great deal of what is included runs contrary to the requirement for it to be, some way or another, performed. As has become normal for narratives on TV, re-authorizations are incessant, with an eventual Warhol substitute displayed from behind or, in any case, in clouded sees rearranging around at home and approaching his day.

The impact is shaking from the outset, yet it becomes harmless enough as the musicality of such scenes squeezes into the main episode’s sluggish and patient pacing (which develops considerably increasingly slow persistent in the five episodes that follow, each around an extended).

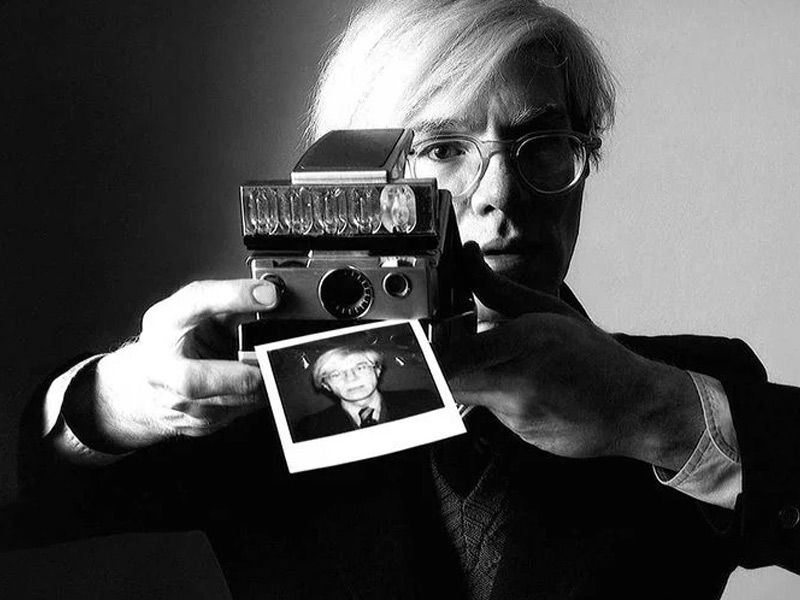

More eyebrow-raising is the presence of portrayal by a recreation of Warhol’s voice made via man-made reasoning. Attracting on the message to discourse innovation layered with recorded readings by an entertainer (Bill Irwin), the computerized simulacrum of a voice successfully recounts the journal passages as Warhol initially communicated them via telephone.

It is an awful thought, and minutes are interesting when the consciousness of the post-human interaction isn’t top-of-mind. In any case, it ends up, despite everything, that the oddity of its functions and turns out to be shockingly moving as the series advances. It likely could that utilize “deepfake” voice reenactment is awful inside and out every other occasion.

Yet, Warhol-an indifferent code which attempted to talk as little as possible and, when compelled to, made a round of avoidance ends up being an extraordinary case, particularly as a large part of the topic of the Diaries is exceptionally enthusiastic in manners that the craftsman himself never was in an expressed manner.

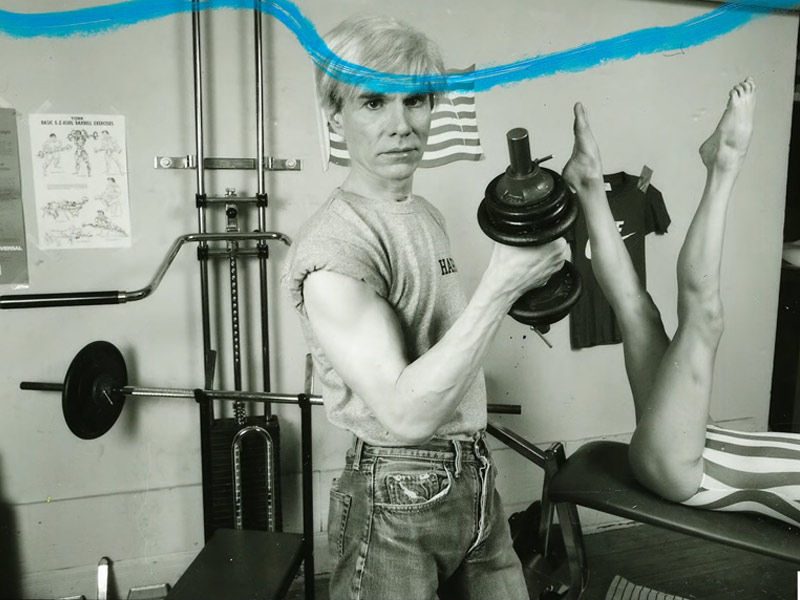

The passionate highs and lows of the Diaries are the primary focal point of the series, which has been promoted with the slogan “The art you know. The artist you don’t.” And passionate highs and lows overall, as well as specific signs of each relating to Warhol’s affection life and his relationship with various parts of orientation and sexuality.

The primary episode takes care of Warhol’s ascent, from his childhood as an offspring of Slovakian migrants in Pittsburgh to his climb to fame in New York, before subsiding into the years when the text of the Diaries starts, in 1976. The surge of the developmental Factory years comes to an unmistakable limit after Warhol is shot and almost killed by SCUM Statement creator Valerie Solanas in 1968.

After this point, the glitz disapproved of craftsmen turned more protected. Private-and furthermore went gaga for Jed Johnson, an inside architect. The latter moved in with him to assist him with convalescing.

Also Read, Autumn Girl: A Beautiful Cinematography by Polland

The quality of family life that Johnson and Warhol developed together in Warhol’s apartment on the Upper East Side is a focal point of the initial two episodes, which move to and fro between Warhol’s advancement as a “business artist” arranging expensive representations on commission and his significantly more mysterious private life. Johnson’s twin sibling Jay Johnson talks straightforwardly and movingly about the relationship his sibling (who passed on in 1996, in a business plane accident) attempted to sustain before Warhol began to wriggle.

At a certain point in episode two, Warhol talks (utilizing the reproduced voice) of becoming flushed when Jed Johnson’s folks visited and expressed gratitude toward him for being so great to their child. However, as they hung out, Warhol started to give himself to nightlife revelry at objections. For example, Studio 54, apparently as a method for being away from home. Their relationship has failed before the episodes finish, with a sizable amount of trouble to go around.

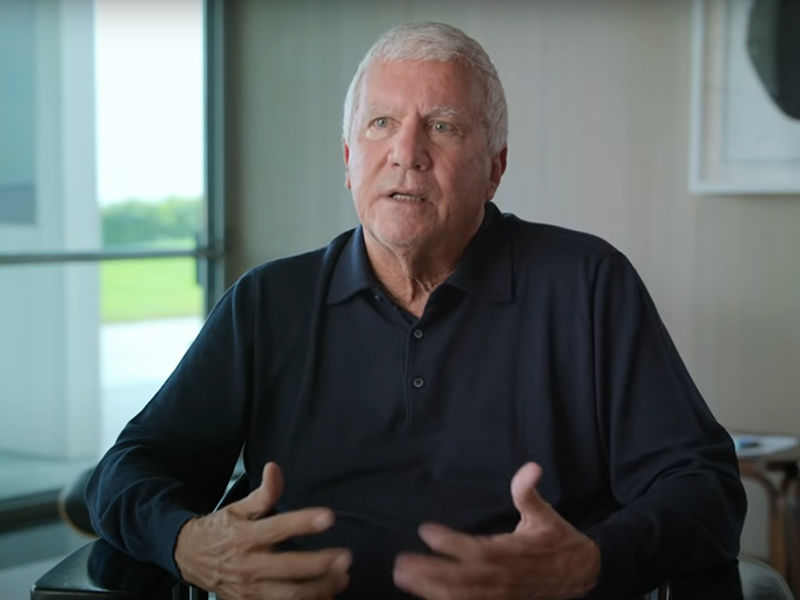

Enter Jon Gould, a leader at Paramount Pictures. Warhol began sending roses in an applied exertion at romance that amazed everybody around him. Weave Colacello, one of the craftsmen nearest relates at that point and creator of the 1990 Warhol tell-all Holy Terror, noticed that similar to Johnson, Gould additionally had a twin sibling ideal for Warhol’s “fascination with twins, which is very Pop art. Repetition. Andy loved repetition.” That Gould could be mistaken for straight and regularly did is of extraordinary interest to Rossi, the chief, who dedicates the main part of episodes three and four to Warhol and Gould.

Through varying levels of closeness and distance, both appeared to explore cheerful times, for example, a gathering trip with companions to Cape Cod caught with incredibly cozy individual video while staying a secret to people around them. At a certain point, Colacello says, “I remember Steve Rubell, who Andy sort of confided in … Steve once said to me, ‘Jon Gould just dances naked for Andy, and that’s their idea of sex and whatever.’… I love that Tallulah Bankhead commented when she learned that Montgomery Clift was gay, and she said, ‘How would I know? He never sucked my cock.'”

Pressure between the abiogenetic quality that Warhol anticipated and the strangeness he has so obviously enchanted with stays a point of convergence of the series as it wanders into different subjects, for example, Warhol’s coordinated effort on a progression of artworks during the 1980s with Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Colacello says Warhol “was intrigued with Jean-Michel, in both a fatherly and gay way.” While their work together brought the two specialists accommodating eruptions of consideration (Warhol’s distinction was hailing at that point), their relationship was confounded. In one of his numerous appearances all through the series, the craftsman Glenn Ligon says, “I think it is feasible to have two contradicting perspectives simultaneously.

There’s a ton of love there, even though in the Diaries and different spots he criticizes Basquiat.” (The show then, at that point, slices to a Diaries section that peruses: “I believe he will be the Big Black Painter. I think Jean Michel’s initial stuff is better … what number of shouting Negroes would you be able to do?”)

While it comes up as a subject on a few occasions beginning from the get-go in the series, the apparition of HIV/AIDS and the manners in which it crushed eccentric networks in New York turns into a ruling presence in the later episodes. A ton of time is given to a celebrated Diana Ross show in Central Park in 1983 plagued by a Biblical storm of downpour, with unfavorable imagery lost on nobody included. Gould was a maker of the show, and how it’s addressed in the series causes it to seem like one of those minutes that, as Don DeLillo composed of the death of JFK, “crushed the spirit of the American century.”

Warhol’s anxiety toward AIDS includes conspicuously in the Diaries during the ’80s, with numerous passages like the one about Calvin Klein: “And afterward Calvin came in, and he kissed me so hard, and his facial hair was stubbly, and I was reluctant to the point that it was puncturing into my pimple and resembling a needle giving me AIDS. So if I’m gone in three years….”

The Netflix series is extremely strong regarding AIDS, and it sets the pestilence well into the setting of Warhol’s advantage in strict workmanship late in his life. It likewise figures until the end, as Warhol’s anxiety toward emergency clinics and all that they address tormented his experience of the nerve bladder medical procedure that at last killed him at 58 years old. (In the wake of putting off the medical procedure for quite a long time, Warhol proceeded with the strategy but experienced respiratory failure in recovery.)

The series is extremely strong for what it uncovers about so many different craftsman sorts of disclosure around him. Rossi appears to have acquired the trust of the comrades and spectators he talked with, requesting considered and insightful ruminations from any semblance of Bob Colacello, Christopher Makos, Vincent Fremont, Jeffrey Deitch, Glenn Ligon, Lucy Sante, John Waters, Rob Lowe, Fred “Fab Five Freddy” Brathwaite, Greg Tate, Benjamin Liu, and Jessica Beck, a guardian at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh who shares discerning readings of craftsmanships and finds from the craftsman’s document.

Rossi likewise appears to have jumped profoundly into a perplexing text that holds privileged insights more uncovering than what generally sparkles brilliantly on a superficial level.

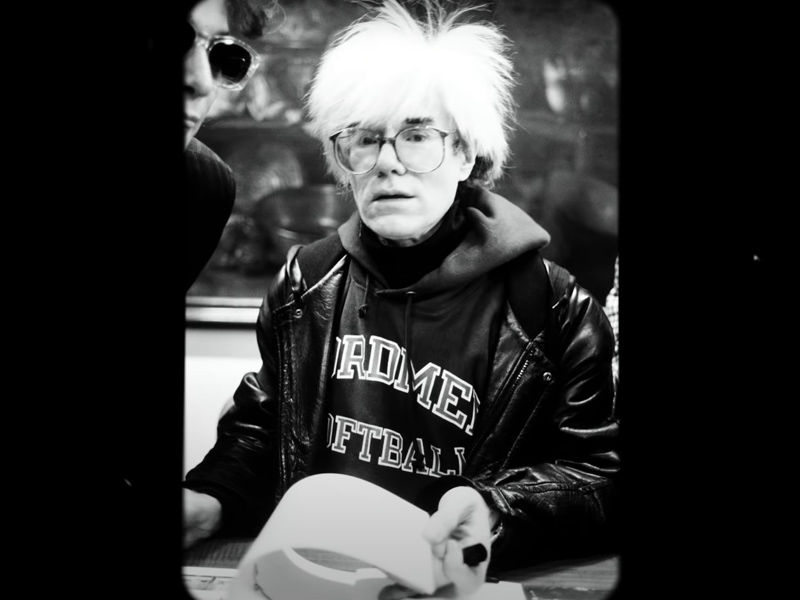

In moving film from a dedication for Warhol at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, John Richardson, the recognized craftsmanship student of history, says, “Even though Andy was seen, with some equity, as an inactive spectator, I might want to review a side of him that he stowed away from everything except his dearest companions: his otherworldly side. Those of you wouldn’t believe that such a side existed.

Be that as it may, exist it did, and it’s the way into the craftsman’s mind. The information on this mysterious devotion unavoidably changes our view of the craftsman into accepting that his main fixations were cash, popularity, and fabulousness. What’s more, that he was cool to the place of insensitivity.”

Talking in a manner for the smart and delicate Netflix series in general, Richardson proceeds, “Never take Andy at his presumptive worth. The insensitive onlooker was truth be told a recording heavenly messenger, and Andy’s separation, the distance he laid out among himself and the world, was, most importantly, an issue of blamelessness and a question of workmanship.”