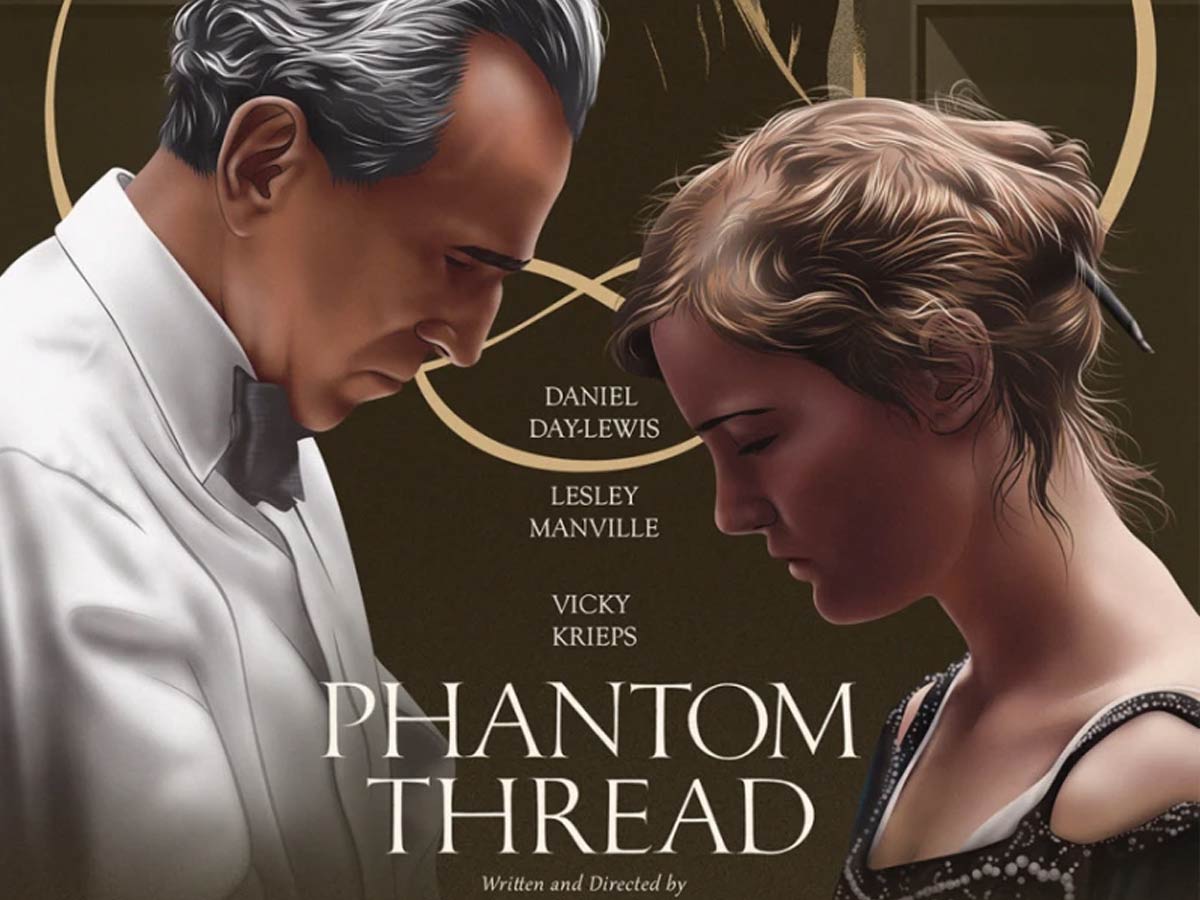

Phantom Thread is an American historical drama film directed and written by Paul Thomas Anderson and, starring Daniel Day-Lewis, Lesley Manville, and Vicky Krieps. It is set in the 1950s London and stars Day-Lewis as an haute couture designer who adopts as his muse a young waitress portrayed by Krieps. It was Day-last Lewis’s film role to date. The film is Anderson’s first to be shot outside of the United States, with main filming starting in January 2017 in Lythe, England.

Anderson’s second collaboration with Day-Lewis after There Will Be Blood (2007), and his fourth with composer Jonny Greenwood. Greenwood’s original music is widely featured in the film.

Superb postwar English couturier: fussy and cantankerous, humourless and ludicrous–and heterosexual, in that pre-Chatterley period when being a bachelor and fashion designer wasn’t inherently connected with anything else in the public consciousness. In this new picture from writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson, Daniel Day-Lewis delivers us his cinematic swan song. Reynolds Jeremiah Woodcock is a famed dressmaker of Britain’s debutantes, but he is under pressure from the New Look and influences from across the Channel. He gives us a superb demonstration of wit on the issue of that unforgivably trite word: chic.

Cast of Phantom Thread

- Reynolds Woodcock is played by Daniel Day-Lewis.

- Cyril Woodcock is played by Lesley Manville.

- Alma Elson is played by Vicky Krieps.

- Johanna is played by Camilla Rutherford.

- Gina McKee plays the Countess. Harding, Henrietta.

- Nigel Cheddar-Goode is played by George Glasgow.

- Dr. Robert Hardy is played by Brian Gleeson.

- Barbara is played by Harriet Sansom Harris.

- Princess Mona Braganza is played by Rose Lujza Richter.

- Lady Baltimore is played by Julia Davis.

- Lord Baltimore is played by Nicholas Mander.

- Peter Martin is played by Philip Franks.

In the Phantom Thread, Woodcock falls in love with a shy, inept German waitress at the country hotel where he is staying, just when he is at his lowest. Vicky Krieps is the character Alma. With his connoisseur’s eye, Woodcock notices a grace and elegance in her that no one else, least of all Alma, has observed. Dazzled, she moves in with him to work as his assistant and model at the central London design firm that Woodcock lords over with his sister and confidante Cyril, played with mysterious reserve by Lesley Manville. However, as Woodcock grows increasingly difficult and demanding, subservient Alma must find new, more destructive methods to re-establish her emotional dominance over him.

Also Read, Yeh Kaali Kaali Ankhein: Enjoy the Love with criminality

Day-Lewis delivers a performance of almost impossibly appealing outrageousness, the kind that only he can pull off. He’s a cross between Hardy Amies and Norman Hartnell, with a dash of Tony Armstrong-Jones thrown in for good measure — definitely, Hartnell’s connection with his sister and business partner Phyllis is evoked here. It’s a cult leadership study comparable to Anderson’s The Master, as well as a portrayal of entrepreneurial loneliness comparable to his appearance in Anderson’s There Will Be Blood.

Woodcock is a preening gorgeous, dramatic, highly strung man with a borderline strange speaking voice, sinuous and refined: an acquired a manner that may hint to a humbler starting than any he will acknowledge to now. This Woodcock possesses the etiolated elegance of a dancer, the misanthropy of an artist, and the carefree hauteur of a lord. It’s the type of guy Day-Lewis has played before–the one who harbours a politely unspoken disdain for the lack of integrity he perceives in everything and everyone around him, particularly the vulgar, moneyed women on whose favour he is obliged to rely.

The amazing scene-setting produced by production designer Mark Tildesley and Mark Bridges’ costumes are influenced by Joseph Losey. The second influence is Hitchcock, with Krieps playing Joan Fontaine in Rebecca and Day-Lewis as aristocratic Max de Winter, as performed by Olivier. Manville is a cross between Mrs. Danvers and Rebecca herself. There are no sugar-rush jukebox 50s classics on the soundtrack to establish the period’s sentimentality, nor are there newspaper ads about Suez or Profumo. We firmly adhere to a broad sense of time and location, as well as an orchestral music by Jonny Greenwood featuring classical classics.

This film is pure exquisite joy, with its weirdness, vehemence, and flourishes of absurdity executed with wonderful grace. And Woodcock’s sartorial inventions have a strange, sumptuous feel, like two dishes at a Roman feast. He has stated that it is, and he is not one to talk carelessly. We must presume that this is the end. Perhaps this is how viewers felt at Nijinsky’s final public performance in 1917, which allegedly moved Arthur Rubinstein to tears. It’s a fantastic high note for Day-Lewis to conclude on: I’m filled with joy and profound despair.

“Phantom Thread” reverses itself, very quietly shifting from Reynolds’ point of view to Alma’s and back again, like a garment that may be worn with the lining on the outside. She first succumbs to what is most certainly a well-planned seduction campaign: Reynolds flirts with her at breakfast, asks her to dinner, takes her back to his country estate, and begins creating her a dress. He perceives her physical faults — tiny breasts, broad shoulders, and wide hips — as marks of excellence. She is astounded by his capacity to be astounded by her.

“Phantom Thread” is what sort of love tale is it? A heartbreaking story about a woman’s love for a guy and a man’s passion for his career. A dry, comedic examination of the inequalities and tensions that exist at the centre of a marriage. A sophisticated gothic nightmare in the style of Henry James. A wicked psychological story about unrestrained ego and uncontrollable desire. That’s only a brief list, and it doesn’t do justice to how odd this film is. Or how strangely real it seems to life–to art, to love, to itself.