Forget The Simpsons and their numerous predictions; one star-studded 1979 Hollywood disaster film managed to foreshadow events that occurred while it was still in theatres.

The China Syndrome, starring Jane Fonda, Michael Douglas, and Jack Lemmon, depicted a corporate cover-up surrounding a nuclear power plant accident.

Atomic energy was viewed as the solution to the country’s growing reliance on foreign oil. Despite the industry’s dismissal of “Jane Fonda’s meltdown” as “disconnected from reality” and instilling unnecessary fear, nuclear physicist Michio Kaku says the film “brought into the vernacular the concept of core meltdown (called The China Syndrome in the film because it could theoretically go through the planet “all the way to China,” when in reality it would result in blast clouds of radioactivity).”

“There was a loud cry from the nuclear industry that this could never happen, but within 12 days, people discovered it could.”

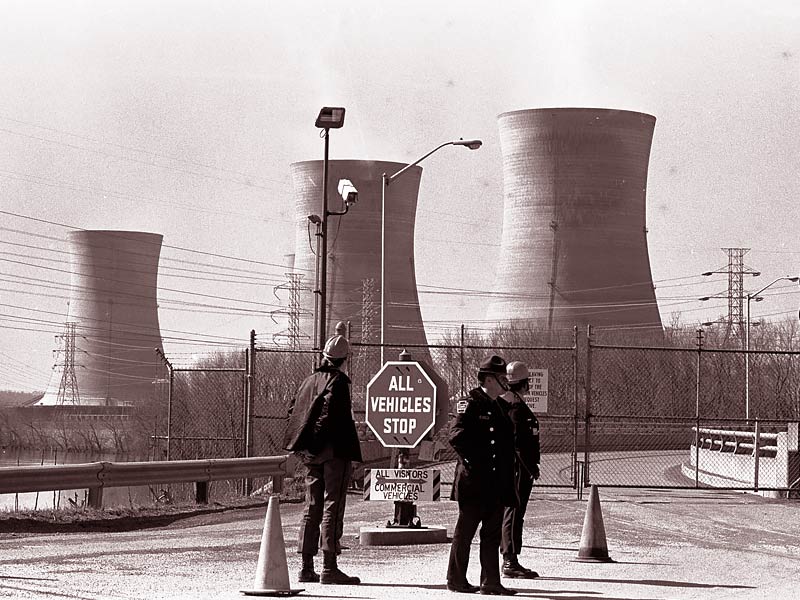

In two ways, the partial meltdown at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania in 1979 was a perfect convergence of factors.

According to the new documentary “Meltdown: Three Mile Island,” a series of cascading mechanical and human errors brought the plant dangerously close to a disaster that could have rendered much of the East Coast uninhabitable.

Second, because it occurred during the height of Cold War paranoia and just days after the release of the film “The China Syndrome,” the disaster was perfectly timed to arouse fears about the dangers of nuclear energy.

“Meltdown: Three Mile Island,” a new four-part Netflix documentary, does an excellent job of weaving together those two truths: that Three Mile Island was a narrowly averted nightmare scenario and that it lives on in the public imagination as an argument against nuclear energy.

It can fall back on undercooked tools of the trade, especially in the early going — reenactments of, say, a phone ringing in a school where children wait for news about the disaster, the camera somewhat schlocky pushing into amp up what’s already dramatic enough. However, the strength of the story “Meltdown” tells, as well as the insight of those on whom director Kief Davidson trains his camera, ultimately wins out.

The reenactments and overtly sentimental touches are most noticeable in the first act, which is focused on the incident and its immediate aftermath. But that is only the beginning of the saga, and it is also the least interesting part. As “Meltdown” progresses, Rick Parks, an engineer with the engineering firm Bechtel, comes to the fore; he describes in minute detail how the cleanup operation, in an effort to save money and time rendered. (One anecdote about the use of duct tape in the cleanup process has to be heard to be believed.)

Also read : Return to Space: Elon Musk makes his Amazing Netflix Debut

Parks, whose life — and, he claims, health — was thrown off course by his role in the Three Mile Island story, is both a fascinating character and a welcome guide to the story’s long tail. The Three Mile Island incident set in motion a botched cleanup that was as effective an argument against the use of what is, when done safely, a clean source of energy as could be marshaled. (In one compelling piece of contemporaneous footage, a homegrown anti-nuclear power activist turns a Pennsylvania town meeting into a roaring display of might, urging her neighbors to express their opposition to venting the plant’s gas.)

Radiation protection supervisor Dick Dubiel takes us through the early hours of March 28, when a problem was discovered and potential errors were made with Three Mile Island’s newly operational Unit 2. Pennsylvania government press secretary Paul Critchlow describes the horror of discovering that their public assurances of residents’ safety were based on false information.

Metropolitan Edison (Met-Ed) plant operator and former Three Mile Island chemistry supervisor Ed Houser tearfully recalls volunteering to check the concentration levels of boron a day after the initial incident, something critical to determining whether it was safe to shut everything down.

“It was like the rapture had happened,” he says of the eerie sight of a now-contaminated room with bites taken out of sandwiches and half-drunk coffee. When he resurfaced, he discovered he had been exposed to 100 times the agreed-upon allowable radiation limit, and he spent “hours in the shower” to try to decontaminate. “It didn’t work very well,” he laments, admitting that he wouldn’t touch his kids for a while because of the risk he thought he posed to them.

The disparate dual narratives quickly emerge, particularly in the news footage of the time. The official line from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and Met-bosses Ed’s was that there was no need for an evacuation, but there was growing concern among public health officials and locals that not all scientific data was being shared with them.

As Rolling Stone magazine’s Ira Rosen recalls, “everyone became an investigative journalist” because they couldn’t – and wouldn’t – believe what they were told at press conferences.

Even the mayor of nearby Middleton, Robert Reid, was caught on camera at the time saying, “I think we’ll get better answers,” once officials started asking for more than just Met-Ed officials for situational updates.